By Jessica Intermill

Editor’s note: This is the second installment of a two-part article exploring structural bias and racism within the law in the context of the Line 3 oil pipeline expansion. Part 1, published last month, examines the agency approval process and the role of the public in that process. Part 2 explores the racialized impact of that facially neutral approval in the context of Minnesota’s legal history.

As Enbridge races to complete its new Line 3 tar sands pipeline across Minnesota, 17-year-old Jaiden Ellington-Vasser grabs a quick bite. School is out for the day, and she has 45 minutes before her clerk shift starts at the grocery store.

1

Photo: April 21, 2021 fire at the North Minneapolis Northern Metals plant. Photo courtesy Robert Hilstrom

Ellington-Vasser knows firsthand that the Public Utilities Commission’s decision to approve construction of the new Line 3 pipeline affects far more Minnesotans than the northern landowners and tribes in Enbridge’s immediate path. She lives in Webber-Camden, a Minneapolis neighborhood that reflects the city’s race-structured past. Every day, Ellington-Vasser lives the unequal de facto effects of historical racism that de jure decisions continue to project into our future. In late May, she joined seven other youth climate activists to seek leave to file an amicus brief in federal litigation against Line 3.2 They argued that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers improperly failed to consider the impact of the Line 3 expansion on urban Minnesotans of color.

Invisible lines

Construction of the new Line 3 began in December 2020 to “replace” an aging pipeline of the same name. But the new line will be both wider and longer than the original line and, if operated at capacity, will more than triple the current Line 3’s annual greenhouse gas output to 273.5 million tons.3

Minnesotans will not bear this greenhouse-gas dump—or the climate change it accelerates—equally. Cities generally warm faster than rural landscapes.4 And an increasing body of research confirms that within cities, “neighborhoods located in formerly redlined areas—that remain predominantly lower income and communities of color—are at present hotter than their non-redlined counterparts.”5

Segregation now

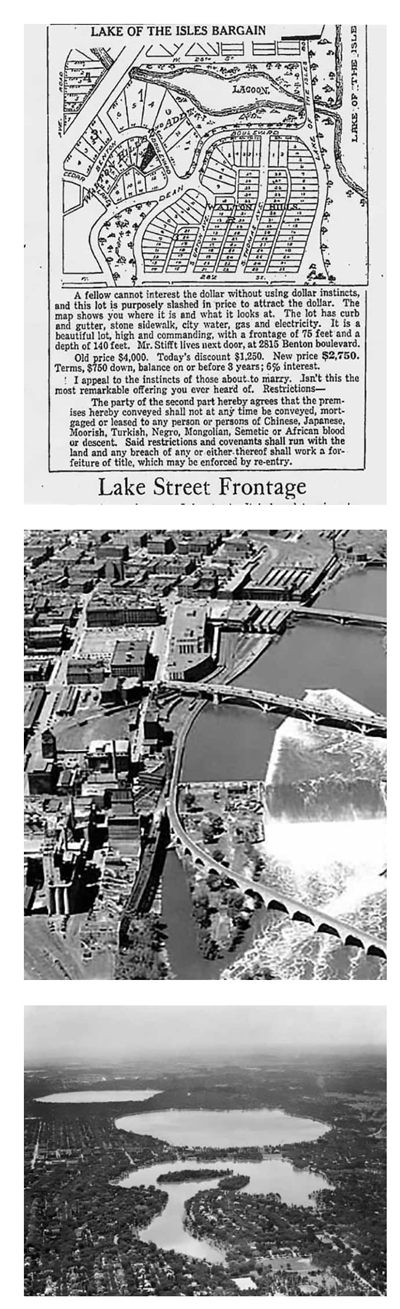

The racialized climate story of Minneapolis began in 1910. When Henry and Leonora Scott sold their property to Nels Anderson, they added a stipulation to the deed that the “premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.”6 The Minneapolis Journal editorial board called for “coordinated action to make neighborhoods all white[,]” and White sellers complied.7 Racial covenants “changed the landscape of the city” by laying “the groundwork for our contemporary patterns of residential segregation.”8

The White Minneapolitans’ intentions were not novel. As one historian noted, “Since the seventeenth century, Americans had proceeded in law and custom as though the blacks were essentially different.”9 A decade after Thomas Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal,” he noted his suspicion that

the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind. It is not against experience to suppose, that the different species of the same genus, or varieties of the same species, may possess different qualifications.10

Photos courtesy Minnesota Historical Society:

1) Advertisement place by Edmund G. Walton in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune, 1919.

2) Aerial view of St. Anthony Falls looking northwest toward north Minneapolis, 1938.

3) Aerial view of southwest Minneapolis looking south from Lake of the Isles to Lake Harriet, 1940.

Responding to Jefferson, abolitionist St. George Tucker said, “If it is true, as Mr. Jefferson seems to suppose, that the Africans are really an inferior race of mankind, will not sound policy advise their exclusion from a society in which they have not yet been admitted to participate in civil rights...?” Yet, even as he argued for emancipation, the abolitionist wrote that “I wish not to encourage their future residence among us.”11

The White Minneapolitans’ methods, though, were new. And they were effective. “As racially restrictive deeds spread, they pushed African Americans into a few small areas of the city. And even as the number of Black residents continued to climb, ever-larger swaths of the city became entirely White.”12

Through the early and mid-20th century, new methods entrenched the segregation that the covenants began.13 Race-rioting White property owners, New Deal-era legislation, and “redlined” federal lending laws pushed people of color—and especially Black Minneapolitans—to the areas we now know as Near North (including Ellington-Vasser’s Webber-Camden neighborhood), Cedar-Riverside (now a center of the metro’s East African population), and Hiawatha (the neighborhood where Minneapolis police killed George Floyd Jr.).14

The inequality of this segregation is visible in today’s landscape. Southwest Minneapolis neighborhoods enjoy tree-lined parkways in a chain-of-lakes landscape. But Minneapolis zoned the “Black” parts of town for industry and density, and then ran a highway right through the north side.

Even the Mississippi River is different in different zip codes. Southeast of St. Anthony Falls, the river’s banks are lined with parkland and the Mississippi National River Recreation Area. Upstream, a Minneapolis-authored report called the riverfront north and west of the falls “the backside of the city.”15

Over time, segregation’s unconstitutionality was no match for its persistence. A University of Minnesota law professor identified government policies and programs that “resegregated” the Twin Cities legally.16 Although facially neutral, programs that clustered new affordable and subsidized housing in historically “Black” areas (coupled with continuing wealth and income inequalities) served to keep historically marginalized Black, brown, and indigenous populations out of most suburbs and out of “White” parts of the Twin Cities.17

Similarly, facially neutral school-choice and open-enrollment policies facilitated White families’ “move from racially integrated schools (or schools in racial transition) to much less racially diverse schools[.]”18 Today’s census maps of the neighborhoods with the highest percentage of non-White residents trace the same lines that the racially restrictive covenants once drew.

Segregation tomorrow

In the first week of June, the Twin Cities had “already tied the record for most 90-degree days at this point in June” and were headed to record the hottest first 10 days of June since recordkeeping began in 1871.19 Those temperatures came barely a month after the Twin Cities had “smash[ed]” an April high-temperature record.20

As extreme heat events like this become commonplace, the continuing impact of Minneapolis’s segregated legacy is more than aesthetic. Areas like north Minneapolis that are most urban and industrialized have become “heat islands” that “absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes” like the south metro’s lakes and parks.21

The effect is stark. 2016 data from the Metropolitan Council shows that the land surface temperature in heat islands can be more than 10 degrees hotter than other parts of Minneapolis and St. Paul (which are themselves up to 10 degrees hotter than many first-ring suburbs).22

This extreme heat is deadly. Minnesota recorded 54 heat-related deaths from 2000 to 2016, and the state Department of Health has noted that the progression of climate change will make this problem worse.23

The warming atmosphere also traps air pollution. In 2013 alone, according to a 2019 joint report from the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), the health effects of air pollution occasioned 500 hospital stays and 800 emergency room visits, and contributed to the premature deaths of 2,000-4,000 Minnesotans.24 These health effects, too, are not uniform. Nationally, “Black people are nearly four times [more] likely to die from exposure to pollution than White people.”25 In Minnesota, the ecological effects of heat islands layered on top of historical segregation patterns mean that air pollution trapped by global warming is “inequitably distributed among racial and ethnic groups in the state[,]” and “[p]eople of color experience an undeniable ‘pollution disadvantage.’”26

Jaiden Ellington-Vasser already lives this pollution disadvantage. She points to the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center located just south of her neighborhood. That plant incinerates waste to generate electricity. Hennepin County pledges that “[a]ir emissions are cleaned and treated so that emissions are consistently below the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency permitted levels.”27 But low is more than none, and the county does not operate garbage burners in southwest Minneapolis.

The Northern Metal Recycling plant is even closer to Ellington-Vasser’s home. Community members complained for years about pollution from its metal shredding operation on the north Minneapolis Mississippi riverfront. A consent decree closed the metal shredder in 2019, after a whistleblower revealed that the company altered pollution records.28 But other operations at the junkyard continued, and after a week-long fire at an exurban facility hampered company operations, a judge allowed Northern Metal to accept scrap in north Minneapolis again.29 In April 2021, scrap metal and rubbish at the north Minneapolis site spontaneously combusted, blanketing the area with black smoke and chemical odors.30

A new Line 3 supercharges these health inequalities with an additional 193 million tons of greenhouse gases.31

Segregation forever?

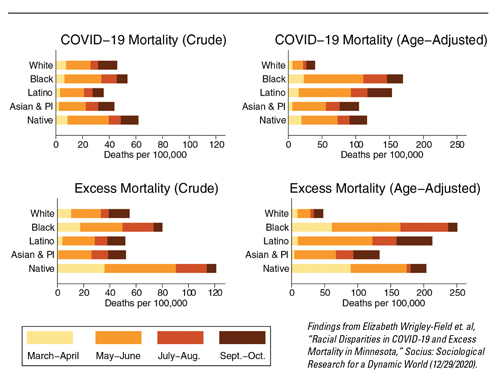

In 2020, it got worse. The covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the deadly effect of the pollution disparity. Ellington-Vasser hasn’t been infected with covid-19. “My mom is very protective,” she said. But others in her family have. And “one of my close friends, her mom passed away from covid last year. It’s really hard for her right now.”

Her story is one of the thousands of Minnesotans who died from covid-19. In context, it is a story that happens much more frequently in historically segregated communities. Long-term exposure to particulate pollution increases a person’s risk of covid-19 death by a factor of 20. Even a slight increase in air pollution was “associated with a 15 [percent] increase in the Covid-19 death rate[.]”32

“North Minneapolis has the worst air in Minnesota,” said Ellington-Vasser. “We have a trash burning facility right here. And since we have the worst air in Minnesota, a lot of my friends and family have asthma. And then think about covid. It attacks the lungs. So you have greenhouse gases that are already bad for the air. You add something on top of it: trash burning puts toxins in the air. And you keep adding on. It’s thing after thing after thing, and they’re all connected. They’re all connected. And if one thing tips, then what are we going to have?”

For Ellington-Vasser, approval of Line 3 was one more thing. In addition to exacerbating pollution over her home, Line 3 tunnels through the Mississippi River—the drinking water source for Ellington-Vasser’s family and the rest of Minneapolis—at multiple points. “It’s scary,” she says. “To be honest with you, it’s very scary.”

Her fear finds support in the administrative record of Line 3’s approval. The spill analysis for the Environmental Impact Statement that underlies permitting for a new Line 3 specifically expects leaks. It concluded that a spill of less than .1 barrel—almost a half gallon—of tar sands crude “might be expected once every four months; a spill of less than 10 bbl [42 gallons], once every 16 months; and a spill of less than 100 bbl [420 gallons], once every 7.5 years.” Larger spills can “be expected once in 26 to 99 years somewhere in the state of Minnesota.”33

In light of this undisputed science, life without Line 3 would be “one less challenge” for Ellington-Vasser. She continued, “For me as an African-American young woman, I have a lot of struggles. With everything going on with George Floyd, there’s a lot going on with civil rights and safety, and I don’t want to be worried about my health. I’m already worried about all these other things, and I don’t want to have to worry about what happens if I turn on the sink water.”

On June 1, the same day that Enbridge restarted construction after a planned spring recess, Attorney General Keith Ellison joined Ellington-Vasser and other Youth N’ Power leaders on the steps of the Capitol. The group presented Ellison with a copy of their proposed amicus brief. Assistant attorneys general are arguing both sides of a state-court case that pits the Minnesota Department of Commerce against the Public Utilities Commission in Commerce’s appeal of the PUC’s approval of the Line 3 expansion. When Ellison asked the group what motivated them to get involved in the climate-justice fight, Ellington-Vasser described her own experience learning about the intersection of climate change and environmental discrimination. “Once my eyes were opened,” she asked, “how could I close them?”34

The stratified reality of Minneapolis is this: Decision-makers pushed Black and brown residents to specific neighborhoods, covered those neighborhoods in concrete and asphalt that created heat islands, zoned the neighborhoods for industry alongside homes and schools, and then approved a pipeline that will accelerate the climate change that traps pollution over these citizens. The discriminatory choices of 20th century Minneapolitans raised the past year’s pandemic death toll in historically segregated neighborhoods like Webber-Camden. And although the decision to allow Line 3 was facially race-neutral, laying its environmental effects atop already-created inequalities means that the detrimental health effects of Line 3’s air and water pollution will have profound impacts on the Black, brown, and indigenous communities that White Minnesotans isolated alongside industry.

We live not alone

Just two decades after Minnesota’s admission to the Union, the Rev. Edward D. Neill and Charles S. Bryant put pen to paper. In 1849, at age 29, Neill had delivered the invocation to the first sitting of Minnesota’s territorial legislature; by 1864 he was President Lincoln’s private secretary. He wrote mission statements for St. Paul’s first public schools, founded Macalester College, and, as a hobby, looted indigenous graves.35 Bryant was a lawyer who prosecuted settlers’ property claims in the wake of the U.S.-Dakota War, which he called “an epoch in the history of savage races.”36 Together, in 1882, Neill and Bryant wrote:

We live not alone in the present, but also in the past and future. We can never look out thoughtfully at our own immediate surroundings but a course of reasoning will start up, leading us to inquire into the causes that produced the development around us, and at the same time we are led to conjecture the results to follow causes now in operation. We are thus linked indissolubly with the past and the future.

If, then, the past is not simply a stepping-stone to the future, but a part of our very selves, we cannot afford to ignore, or separate it from ourselves as a member might be lopped off from our bodies; for though the body thus maimed, might perform many and perhaps most of its functions, still it could never again be called complete.37

Today, 139 years later, our laws dovetail with Neill and Bryant’s “causes [then] in operation” to create the “results” that they and other Minnesotans conjectured. Today’s Minnesota bar did not invite our state’s history of racism and white supremacy, but neither can we ignore it. Facially neutral laws and policies—like the approval of Line 3—cannot be “called complete” if they do not reckon with the past and future to which we are indissolubly linked.

JESSICA INTERMILL helps governmental clients build inclusive processes and advises tribes and their partners on federal Indian law matters and treaty rights, and represents Youth N’ Power in their amicus participation in federal litigation against the Line 3 expansion. She practices on Dakota land taken by the 1851 Treaty of Mendota.

Notes

1 All quotations from Jaiden Ellington-Vasser are from a 3/23/2021 interview with the author unless otherwise noted.

2 After the first article in this series went to publication, the author represented these amici, a cohort of the Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light’s Youth N’ Power program, pro bono in federal litigation against the Line 3 expansion. The federal litigation is consolidated under case Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, Civ. 1:20-cv-0317 (D.D.C.), and summary judgment briefing is pending. The author has no role in litigation against the Line 3 expansion that is also currently pending in Minnesota state court.

3 See generally, Jessica Intermill, “When the Public Interest Isn’t: Minnesota’s approval of a new Line 3,” Bench & Bar of Minnesota, May/June 2021 at 22.

4 A. Borunda, Racist housing policies have created some oppressively hot neighborhoods, National Geographic (9/2/2020), available at https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/racist-housing-policies-created-some-oppressively-hot-neighborhoods (last visited 6/8/21).

5 J. Hoffman, V. Shandas, N. Pendleton, The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas, Climate, Vol. 8, Jan. 2020, at 11, available at https://www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/8/1/12/htm (last visited 6/8/2021).

6 Kirsten Delegard, Racial Housing Covenants in the Twin Cities, MNopeia, available at https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/racial-housing-covenants-twin-cities (last visited 6/8/2021).

7 Id.

8 Mapping Prejudice: What are Covenants, University of Minnesota, available at https://mappingprejudice.umn.edu/what-are-covenants/index.html (last visited 6/8/2021).

9 Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny, Harvard University Press (1981) at 102.

10 Id. at 101 (quoting Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1787; reprint ed., Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955)).

11 Id. at 102 (quoting St. George Tucker, A Dissertation on Slavery With a Proposal for the Gradual Abolition of it in the State of Virginia (1796; reprint of 1861 ed., Westport, Conn.: Negro Universities Press, 1970)).

12 Mapping Prejudice: What are Covenants, University of Minnesota, available at https://mappingprejudice.umn.edu/what-are-covenants/index.html (last visited 6/8/2021).

13 For a history of laws that entrenched segregation, see Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (2017).

14 Mapping Prejudice: What are Covenants, University of Minnesota, available at https://mappingprejudice.umn.edu (last visited 6/8/2021) (displaying time-lapse map of Minneapolis restrictive covenant usage); Mapping Inequality, University of Richmond, available at https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=11/44.972/-93.43 (last visited 6/8/21) (showing Minneapolis redlining); Kirsten Delegard, Racial Housing Covenants in the Twin Cities, MNopeia, available at https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/racial-housing-covenants-twin-cities (last visited 6/6/2021) (summarizing the Twin Cities’ history of racial covenants); Tom Weber, Minneapolis: An Urban Biography, Minnesota Historical Society Press (2020) at 81-82 (describing a 1909 riot and the Minneapolis Tribune’s commendation that “the residents of Linden Hills have averted the establishment of a ‘dark town’ in their midst.”) and 93 (describing Black migration from 1910-1940).

15 Tom Weber, Minneapolis: An Urban Biography, Minnesota Historical Society Press (2020) at 159.

16 Myron Orfield, and Will Stancil, Why Are the Twin Cities So Segregated? 43 Mitchell Hamline L. Rev. 1 (2017).

17 Id. at § III(A)

18 Id. at 35.

19 Joe Nelson, How close will the Twin Cities come to the record for consecutive 90-degree days?, Bring Me the News (June 7, 2021), available at https://bringmethenews.com/minnesota-weather/how-close-will-the-twin-cities-come-to-the-record-for-consecutive-90-degree-day (last visited 6/8/2021).

20 Paul Huttner, 83 degrees: Twin Cities smashes high temperature record Monday, MPR News (Apr. 5, 2021), available at https://www.mprnews.org/story/2021/04/05/82-degrees-twin-cities-smashes-high-temperature-record-Monday (last visited 6/8/2021).

21 See Heat Island Effect, U.S. EPA, available at https://www.epa.gov/heatislands (last visited 6/8/21).

22 Metropolitan Council, Extreme Heat Map Tool, available at https://metrocouncil.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=fd0956de60c547ea9dea736f35b3b57e (last visited 6/8/2021).

23 Extreme Heat Events, Minnesota Department of Health, available at https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/climate/docs/extremeheatsummary.pdf (last visited 6/8/2021).

24 Life and Breath, MN Department of Health & MN Pollution Control Agency, available at https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/aq1-64.pdf at 1 (last visited 6/8/2021).

25 Darryl Fears and Brady Dennis, “This is Environmental Racism,” The Washington Post, Apr. 6, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/interactive/2021/environmental-justice-race/?utm_campaign=eng-rem-evg&utm_medium=acq-nat&utm_source=facebook&utm_content=climate-environmentalracism&fbclid=IwAR2cqReCXVIgDasbMq0iS3Fneh_mQ6OUDpijij_weSGX7vsDcc73QQAT-Fc (last visited 4/27/2021).

26 M. Cecilia Pinto de Moura, Who Breathes the Dirtiest Air from Vehicles in Minnesota, Union of Concerned Scientists, Feb. 3, 2020 available at https://blog.ucsusa.org/cecilia-moura/who-breathes-dirtiest-air-from-vehicles-minnesota (last visited 6/8/2021).

27 Hennepin County Energy Recovery Center, available at www.hennepin.us/your-government/facilities/hennepin-energy-recovery-center (last visited6/8/2021).

28 Marissa Evans, North Minneapolis residents welcome shutdown of metal shredder, Star Tribune (Sept. 30, 2019) available at https://www.startribune.com/north-minneapolis-residents-welcome-shutdown-of-metal-shredder/561642752/ (last visited 6/8/2021).

29 Elizabeth Dunbar, Judge allows some Northern Metal operations to resume; city to reinspect Minneapolis site, MPR News (Feb. 28, 2020) available at https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/02/28/judge-allows-some-northern-metal-operations-to-resume (last visited 6/8/2021).

30 Alex Chhith, Fire knocked down at recycling facility in north Minneapolis, Minneapolis Star Tribune (Apr. 21, 2021), available at https://www.startribune.com/fire-knocked-down-at-recycling-facility-in-north-minneapolis/600048722/?refresh=true (last visited 6/8/21).

31 Minnesota Commerce Dep’t, Line 3 Final Environmental Impact Statement at 5-466, Table 5.2.7-12, available at https://mn.gov/eera/web/file-list/13765/ (last visited 6/8/2021).

32 D. Carrington, Air pollution linked to far higher Covid-19 death rates, study finds, The Guardian (Apr. 7, 2020), available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/07/air-pollution-linked-to-far-higher-covid-19-death-rates-study-finds (last visited 6/8/2021).

33 Minnesota Commerce Dep’t, Line 3 Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix S Baseline Pipeline Spill Analysis at 41, available at https://mn.gov/eera/web/project-file?legacyPath=/opt/documents/34079/Line%203%20Revised%20FEIS%20Appendix%20S%20Spill%20Analysis.pdf (last visited 6/8/2021).

34 Northside Youth File Line 3 Amicus Brief in Federal Court, Deliver a copy to AG Ellison at Minnesota Capitol, Minnesota Interfaith Power & Light (June 1, 2021), available at https://www.facebook.com/149272995089877/videos/229741975272542 (last visited 6/8/21).

35 Liam McMahon, Who was Edward Duffield Neill?, The Mac Weekly (Oct. 31, 2019), available at https://themacweekly.com/76882/neill-hall/who-was-edward-duffield-neill/ (last visited 6/8/21).

36 Charles S. Bryant & Abel B. Murch, A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians, in Minnesota (1864).

37 Edward Duffield Neill and Charles S. Bryant, History of the Minnesota Valley: Including the Explorers and Pioneers of Minnesota (1882).