By Jessica Intermill

Editor's note: This is the first installment of a two-part article exploring structural bias and racism within the law in the context of the Line 3 oil pipeline expansion. Part 1 examines the agency approval process and the role of the public in that process. Part 2 explores the racialized impact of that facially neutral approval in the context of Minnesota's legal history.

On a spring morning in 2018, Minnesota Public Utilities Commissioner Katie Sieben began reading a prepared statement. “There is no good outcome,” she said, “where I can sleep easy at night knowing I made the right decision with the facts available.”

1

She spoke to a crowd that filled the St. Paul conference room and spilled into hallways and auxilliary rooms. They had come to hear the decision of the five-member Minnesota Public Utilities Commission regarding Line 3. Enbridge, a Canadian energy-transportation company, was seeking to build the new oil pipeline across northern Minnesota and could not do so without PUC approval of a certificate of need and route permit. But Commissioner Sieben was not the only one who struggled.

An hour into the meeting, Commission Chair Nancy Lange reached for tissue to blot tears as her words caught in her throat.2

“It feels like a gun to our head that somehow compels us to approve a new line,” Commissioner Dan Lipschultz said shortly afterward.3

The commissioners unanimously approved the certificate of need, a crucial step toward a new Line 3.

Enbridge billed its project as a “replacement” for an existing pipeline of the same name that brings Canadian tar-sand oil to market. The current 34-inch Line 3, in place since the 1960s, only operates at about half-capacity. The new 36-inch pipeline will not follow the 282-mile line it purports to replace. Instead, Enbridge sought permission to abandon the existing pipeline and tear a largely new 337-mile path. The new Line 3 would carry 760,000 barrels of crude oil—nearly 3.2 million gallons—across Minnesota every day.

That crude would tunnel through the Mississippi River at two different points, including near its headwaters. It would cross 192 surface waters and various state-designated trout streams; run within 1,000 feet of 3,913 wetlands, 88 streams, and 57 lakes; and tunnel within a half-mile of 17 wild rice lakes. The route largely stretches across land ceded by treaties that the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized protect tribal members’ right to “hunt[], fish[], and gather[] the wild rice, upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded.”4 In 2019, the Minnesota Court of Appeals vacated the 2018 certificate of need because it rested on an inadequate Environmental Impact Statement.5

When the PUC reconvened last year, Winona LaDuke addressed the commissioners on behalf of intervenor Honor the Earth. “We know each other because I’ve been coming here for seven years,” she said. “For seven years, I’ve been driving down from my reservation in northern Minnesota to your hearings. I’ve done that because I want the system to work.”6 She had heard Commissioner Lipschultz two years earlier describe the gun to his head compelling him to approve Line 3. Approving permits for the line, though, said LaDuke, “is putting a gun on my head.”7

The PUC states that a “key function[] of the commission” is to “balance the private and public interests affected” by each project and “appropriately balance these interests in a manner that is ‘consistent with the public interest.’”8 But questions that hang on a “public interest” analysis often turn on what interests—and which public—decisionmakers prioritize.

The PUC’s interest in utilities

Since its beginning, the PUC’s predecessor agencies prioritized expansion of cheap utilities—often over public opposition.

One of the earliest “public interests” that Minnesota courts identified was railroad expansion. That interest was so strong that it displaced otherwise ordinary landowner remedies like ejectment.9

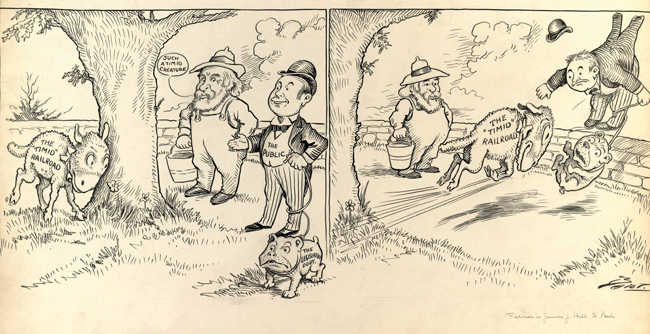

The PUC traces its origin to this interest. Its ancestral predecessor was established by 1871 legislation that began with rail safety inspections, but just three years later turned to railroad-rate oversight. An 1885 law continued to focus on rate discrimination without any countervailing concern that utility expansion could undermine other public interests. But even then, contemporary critics noted that expansion of utilities like railroads prioritized the interests of capital over people. A 1907 political cartoon showed railroad baron J. J. Hill demur at the “timid creature” while the railroad industry knocked “the public” off its feet.

“The Railroads — A Timid Creature.” Illustration by Charles L. Bartholomew, Minneapolis Journal 1907, courtesy Hennepin County Library.

The public’s interest in Line 3

Fast forward a century. The Environmental Impact Statement made clear that a new Line 3 would more than triple the current Line 3’s greenhouse gas output to 273.5 million tons per year.10 That’s about the same as adding 50 new coal-fired power plants or 38 million vehicles. The EIS also confirmed that “Wild rice lakes, many of which are designated for use by American Indians or designated as Traditional Cultural Properties... would be impacted.”11

Beyond ecological impacts, the EIS noted that Enbridge situated its preferred line route through census tracts with “minority populations that meaningfully exceed their county levels,” namely, through indigenous populations.12 This siting implicated treaty rights and amplified concern “regarding the link between an influx of temporary workers and the potential for an associated increase in sex trafficking, which is well documented, particularly among Native populations.”13

The Department of Commerce’s Division of Energy Resources—whose sister division conducted the EIS and held 49 “open mic” public meetings to receive comments on that analysis—opposed the line. It concluded that “in light of the serious risks and effects on the natural and socioeconomic environments of the existing Line 3 and the limited benefit that the existing Line 3 provides to Minnesota refineries, it is reasonable to conclude that Minnesota would be better off if Enbridge proposed to cease operations of the existing Line 3, without any new pipeline being built.”14

An administrative law judge, too, took extensive public comment to prepare the administrative record of the certificate of need and route permit for the PUC. She conducted 16 hearings across the state attended by about 5,500 people, building a record of public comment from 724 speakers that was over 2,600 pages long. In each city, she held separate hearings in the afternoons and evenings to accommodate the schedules of people who work both days and nights. After the three-month process, she completed a 300-plus-page report that included more than 40 pages summarizing public comments concerning the new Line 3.15

Not everyone opposed Line 3. Several labor unions, for example, intervened to support approval of the new Line 3 as a job creator in a region experiencing an economic slowdown. But the ALJ emphasized that unlike the interests of Enbridge—a modern-day Canadian J. J. Hill—the public’s interest was in construction; it was not a specific endorsement of a new Line 3.

“The importance of these economic benefits to northern Minnesota are not insubstantial,” the ALJ found, but rather “would exist with respect to any infrastructure project of this magnitude.”16 Thinking past Line 3 to build a renewable-energy infrastructure with union-protected prevailing-wage jobs would satisfy the public interest in economic development and water quality. But only Line 3 was on the table.

Of 72,249 written public comments submitted, 68,244 opposed a new Line 3.17 The ALJ recommended against Enbridge’s request because it did not “minimize[] the impacts on human settlement, the natural environment, the economics within the route, the State’s natural resources, and the cumulative potential effects of future pipeline construction.” She favored a “true replacement” in the existing trench.18

But the ALJ wasn’t the decisionmaker.

The PUC’s interest in the public

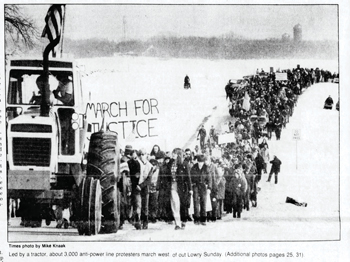

The PUC’s embedded bias toward utility expansion has long blinded it to the interests of any larger public. In the 1970s, electrical co-ops sought to build a 430-mile-long high-voltage line through 476 farm properties in west-central Minnesota. Powerline opposition, described in scholarship by the late U.S. Sen. Paul Wellstone, was broad.19

3,000 people joined the Pope County “March for Justice” to demonstrate against the proposed powerline. St. Cloud Daily Times, March 6, 1978. Photo by Mike Knaak.

The law was, conceivably, in the farmers’ favor. The 1971 Minnesota Environmental Rights Act applied to the project and declared the state’s policy “to promote efforts that will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of human beings[.]”

20 A law requiring that the agency’s power plant and transmission siting decisions consider and “comport with the public interest” also applied to the project.

21

More than 60 percent of all Minnesotans and 70 percent of rural Minnesotans opposed the line.22 The Minnesota Energy Agency, the agency then designated to review applications for certificates of need, approved it anyway.

So it was for the new Line 3.

After months of taking public comment, a multi-week evidentiary hearing, and a 400-page report, the process moved from the ALJ to the PUC. Like a set of filters, the permitting process squeezes public comment through an increasingly fine sieve. In the contested-case process, the ALJ collected undiluted comments from the public and distilled them into a report. The PUC staff took that 400-page report and ground it—and 55 other documents—into 46 pages of “staff briefing papers” that recommended granting Enbridge the certificate of need and its preferred expansion route.23

The staff briefing did not include any discussion of the extensive public comment on the case. But it did note that “the Commission need not engage in the exercise of reviewing the ALJ Report” itself since “[t]he Commission traditionally leaves it to staff to ensure that the final written order identifies the parts of an ALJ Report that have been adopted, with or without modification, and the parts [that] have not been adopted.”24

That filtered record moved forward to the five PUC commissioners who sat on the dais in June 2018 to decide whether to grant the certificate of need and route permit.

Commissioners had decided not to move those decisive meetings from their accustomed conference room to a larger one, despite “the large number of parties and the significant public interest in the case[.]”25 They reserved 60 percent of the 173 seats for parties, press, and staff, leaving only around 70 “general admission” seats for the public who had submitted tens of thousands of comments.

The PUC allocated these remaining seats with no-cost tickets on a first-come, first-served basis. Interested attendees showed up increasingly early each day to queue up for the coveted tickets. But when citizens arrived, they found unexpected rules that limited participation.

One member of the public recalled, “Sometimes people were allowed to leave temporarily to use the restroom, other times doing so meant forfeiting your seat for the day.”26 Another noted, “Sometimes we could switch out the people in line, sometimes we couldn’t. Sometimes we could bring water bottles in, the next we day we couldn’t.”27 The prohibition on water bottles at the meetings, which would often stretch for hours and sometimes the whole day, “was particularly frustrating for some attendees.”28

Some of the parties weren’t much better off. Enbridge and the intervenors could skip the line with “party tickets” that reserved their seats. Most parties received five tickets each. But the PUC allocated the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians and White Earth Nation—two different parties, both of whom the ALJ had allowed to intervene to defend their separate interests—a total of five tickets to share between the two. The PUC gave 10 reserved tickets to Enbridge.

On June 4, 2018, faith leaders delivered a letter with 575 faith leader signatures, including five bishops, to the PUC and to the governor’s office. Photo courtesy Julia Nerbonne, Minnesota Interfaith Power & Light.

That 2018 meeting stretched on for several days to determine whether to grant the certificate of need and to consider Enbridge’s preferred route. After opening statements, though, the commissioners directed the hearing, posing their own questions to the parties they wanted to hear from, and making their own statements into the record. The public could not comment at the hearing and parties could not rebut or cross-examine the testimony of other parties.

Meanwhile, as the days progressed, PUC staff “thought certain parties abused their reserved tickets by distributing them to individuals that staff did not consider to be party representatives, such as children.” The PUC, though, had no policy defining who could serve as a party representative. Even as the public fought to enter the room, “many of the seats reserved for parties went unoccupied.”29

Tensions escalated when, at PUC staff direction, St. Paul police removed two individuals with party badges from the building “because they were holding more than one ticket at a time.”30 Here too, the “rule” purportedly violated was not contained in any notice. PUC staff nonetheless refused to let the party representatives return.

Unsure who to contact to get their clients back into the building, the affected parties docketed a letter addressing the commissioners they appeared before.31 When the chair reopened the meeting the following day, she acknowledged the filing but said the commission would not address it because it was not the subject of the hearing. One intervenor responded with “an irregular oral objection[.]”32 When the chair began to call the docket, counsel for the Sierra Club interrupted, pleading, “I am in this room as a contract attorney without a client.”33 The meeting recessed.

Once reconvened, nerves continued to fray. Near the end of the same day, when the chair noted that another intervenor rose to offer a germane comment, Commissioner John Tuma shrugged that he didn’t “need to hear from” the intervenor, but relented to accept the comment “if somebody else wants to hear from them.”34

The PUC granted Enbridge a certificate of need on a 5-0 vote and allowed the Canadian company to cut its new preferred route across Minnesota. The commissioners pushed what they called a gun away from their own temples.

Between a court and a bulldozer

It is understandable that agencies harbor their own biases. Judicial doctrines, though, can unintentionally import these agency interests into case law. Take again the case of the 1970s Power War. When the Minnesota Supreme Court reviewed the MEQB’s powerline decision—and the board’s failure to undertake early environmental analysis—it deferred to the agency even as it expressed hesitation.

The farmers, the Court said, raised “serious questions about the conclusory nature of much of” the agency’s environmental analysis.35 And the Court agreed that it “may also be true that MEQB in the future should be more vigilant in protecting the alleged interests of the public and that it should play more of an active role as an advocate of environmental values.”36 But “[t]hese considerations” could not disturb the agency’s environmental review.37 As the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals noted in a different environmental case, this is the “difficulty of stopping a bureaucratic steam roller, once started[.]”38

Today, 50 years into that “more vigilant” future, our courts must ensure that the public interests that our Legislature values are ones that agencies meaningfully consider.

Toward a broader public interest

Last year, Minnesota’s Office of the Legislative Auditor issued a report detailing the PUC’s public-participation processes in general, and the Line 3 processes in particular.39 It wasn’t pretty.

When asked directly, PUC commissioners say that “The role of the public is central and foundational[,]” to PUC decisions, and “It is critically important for the commissioners to have robust public involvement.”40 In theory, grounding the law’s requirements in the perspectives of Minnesotans affected by regulatory decisions ensures that “participants in PUC proceedings help [commissioners] determine how to balance the many criteria in the law.”41

In the case of Line 3, though, the system that purports to rely on public input worked to discourage and discount precisely that input. Decisionmakers are not likely to appreciate the wisdom of a person’s experience when they won’t trust that person with a water bottle.

The legislative auditor concluded its report with a punch list of concrete recommendations to improve the PUC’s public-participation process.42

Reviewing courts, too, must also be alert to biases that can hide behind, and skew, agency decisionmaking. “PUC officials told [the legislative auditor] the Line 3 case was an anomaly and that the agency’s practices, which they believe generally work well, should not be judged on this one case alone.”43 Various courts, though, are reviewing this case.44 A self-confessed anomaly can all too easily cross into an abuse of discretion.

Last year, the PUC revisited its approval of Line 3 to consider a revised EIS. It held the first—and only—public hearing that allowed citizens to speak directly to the commissioners about whether to approve Line 3. Again, most public commenters opposed the project.

Gaagigeyaashiik (Dawn Goodwin), a member of the White Earth Nation, rose to speak to the commissioners. She made reference to the 2018 proceedings. She had testified to the ALJ, but had not been allowed to address the commissioners. “It is my inherent responsibility as a member of the wolf clan to protect the environment and the people. That’s why I sit here today. I was denied the chance to speak during the first round.... I was troubled during that time as I listened to all the deliberations. Commissioner Tuma referenced that he did not understand our connection, the Native American connection, to the land. He likened it to a romantic relationship. I was appalled. I felt very disrespected by those words. But I could not speak.”45

When the meetings concluded, the PUC’s vote was no longer unanimous. Commissioner Schuerger voted against Line 3 three times, concluding that the revised EIS was inadequate, that Enbridge had not proven its case for a certificate of need, and that Enbridge’s preferred route was not in Minnesota’s interest. But he was only one vote.

Enbridge began construction on the new Line 3 in December 2020, and expects to complete the pipeline and begin transporting oil this year.

JESSICA INTERMILL helps governmental clients build inclusive processes and advises tribes and their partners on federal Indian law matters and treaty rights. She practices on Dakota land taken by the 1851 Treaty of Mendota.

Notes

1 Minn. Pub. Util. Comm’n Mtg., June 28, 2018 at 28:25, available at minnesotapuc.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=750 (last visited 3/3/2021).

2 Id. at 1:01:35.

3 Id. at 1:12:25.

4 Treaty with the Chippewa, 7 Stat. 536 (7/29/1837); see also Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, 526 U.S. 172 (1999).

5 In re Applications of Enbridge Energy, Ltd., 930 N.W.2d 12 (Minn. App. 2019).

6 Minn. Pub. Util. Comm’n Mtg., 2/3/2020 at 1:10:15, available at minnesotapuc.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=1136 (“Feb. 3, 2020 PUC Mtg.”) (last visited 3/2/2021).

7 Id. at 5:56:45.

8 Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, About Us, mn.gov/puc/about-us/ (last visited 1.27/2021).

9 Miller v. Green Bay, W. & St. P. Ry. Co., 60 N.W. 1006, 1007 (Minn. 1894); Watson v. Chi., M. & St. P. Ry. Co., 48 N.W. 1129, 1131 (Minn. 1891).

10 Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Line 3 Pipeline Project – Revised, 2/12/2018 at 5-466, available at mn.gov/eera/web/file-list/3196/ (last visited 2/23/2021).

11 Id. at 11-16.

12 Id. at 11-5.

13 Id. at 11-20, 11-22.

14 After extensive review, Minnesota Commerce Department releases expert analysis and recommendation on the certificate of need for Enbridge’s proposed Line 3 oil pipeline project, Minn. Commerce Dept. (9/11/2017), available at content.govdelivery.com/accounts/MNCOMM/bulletins/1b655ef (last visited Feb. 26, 2021).

15 Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Recommendation, OAH 65-2500-32764, Docket 14-916 (Apr. 24, 2018) at §III(A), available at www.edockets.state.mn.us/EFiling/edockets/searchDocuments.do?method=showeDocketsSearch&showEdocket=true (last visited 3/5/2021).

16 Id. at 256 (emphasis added).

17 Id. at 406.

18 Id. at 11, 363.

19 Paul Wellstone and Barry M. Casper, Powerline: The First Battle of America’s Energy War, University of Minnesota Press (2003). With the advent of renewable resources, many of today’s climate advocates believe that expanding transmission infrastructure is a critical part of our needed renewable energy transition.

20 Minn. Stat. Ch. 116D.01 (1973).

21 No Power Line, Inc. v. Minnesota Environmental Quality Council, 262 N.W.2d 312 (Minn. 1977) (citing Minn. Stat. 116C.55-116C.60 (1976)).

22 Steven R. Anderson, Power Line Controversy, MNopedia, available at www.mnopedia.org/event/power-line-controversy (last visited 2/1/2021); Electrifying Minnesota, Powerline Controversy, 1972-79, Minnesota State Historical Society, available at www.mnhs.org/sites/default/files/exhibits-to-go/electrifying-minnesota/emn_powerline_controversy_panel1.pdf (last visited 2/1/2021).

23 Minn. Pub. Util. Comm’n Staff Briefing Papers June 18, 19, 26 & 27, 2018 Agenda, Docket 14-916 (6/8/2018), available at www.edockets.state.mn.us/EFiling/edockets/searchDocuments.do?method=showeDocketsSearch&showEdocket=true (last visited 3/2/2021).

24 Id. at 42-43.

25 Public Utilities Commission’s Public Participation Processes 2020 Evaluation Report, Officer of the Legislative Auditor (July 2020) (“Auditor’s Report”) at 68, available at www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/pedrep/puc2020.pdf (last visited 3/1/2021).

26 Id. at 70.

27 Id. at 75.

28 Id. at 75.

29 Id. at 71.

30 Id. at 77.

31 Sierra Club and Northern Water Alliance Letter to Commission, Docket 14-916 (6/27/2018) available at www.edockets.state.mn.us/EFiling/edockets/searchDocuments.do?method=showeDocketsSearch&showEdocket=true (last visited 3/3/2021).

32 Auditor’s Report, supra note 25 at 78.

33 Minn. Pub. Util. Comm’n Mtg., 6/27/2018 at 22:09, available at minnesotapuc.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=748 (last visited 2/26/2021).

34 Id. at 6:28:45.

35 No Power Line, Inc. v. Minnesota Environmental Quality Council, 262 N.W.2d 312, 327 (Minn. 1977).

36 Id. at 326.

37 Id. at 326-27.

38 Sierra Club v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 645 F.3d 978, 995 (8th Cir. 2011) (quoting Sierra Club v. Marsh, 872 F.2d 497, 504 (1st Cir. 1989) (Breyer, J.)).

39 See generally Auditor’s Report supra note 25.

40 Id. at 13.

41 Id.

42 Id. at List of Recommendations.

43 Id. at 78.

44 Dan Kraker, Minn. Pub. Radio, Line 3 opponents file federal suit to try to block pipeline (12/29/2020), available at www.mprnews.org/story/2020/12/28/line-3-opponents-file-federal-suit-to-try-to-block-the-pipeline (last visited 3/4/2021).

45 2/3/2020 PUC Mtg., supra note 6 at 56:23