Lessons in Lawyering from My Family's Restaurant

By Benjamin R. Kwan

Defeated by another day practicing law, I tried to summon the will to figure out what to make for dinner. No small task after a day of decision-making and shouldering other people’s problems—and I hadn’t even opened the refrigerator yet.

You know the feeling.

I wasn’t making anything for dinner—takeout it would be.

As I scrolled through some Asian options, I marveled for a moment at the prices of entrees—high teens, a far cry from the six or seven dollars my dad had charged for a quart of stir fry at his Chinese American restaurant. But it’s also something I’m glad to see: ethnic restaurants willing to charge what their food is worth, and perhaps plugging more than a few pennies of profit into their pockets for their hard work in a notoriously low-margin business.

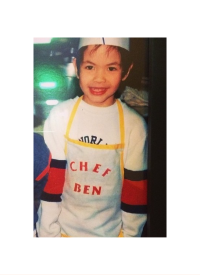

I grew up working in my parents’ restaurants—in south Minneapolis at 54th & Penn until 1995, and then in Eden Prairie until my dad retired. I started washing dishes at the age of five, perched atop an over-turned five-gallon soy sauce bucket and was still helping when Covid hit, and dad needed help getting into the online-ordering game. As I move into my seventh year of law firm ownership on July 1, I’ve taken some time to reflect on all I learned about being an attorney and a law firm owner after nearly 40 years of helping with the family business.

Lesson 1: Identify and Prioritize Your "Cream Cheese Wontons"

I don’t speak anything more than “kitchen Cantonese”: a few cuss words and all the names of popular American Chinese dishes. My dad’s English is the product of quick customer service and Ted Koppel’s Nightline. Not terrible, but limited. Our own communication is deepened and enriched with colorful metaphors and idioms.

In the restaurant, our cream cheese wontons were a staple: pilloried by foodies but picked up by the dozen in our quaint, suburban outpost. James Beard-worthy? Of course not. But they were a cinch to make, cheap to stock, and high-margin to sell (the highest!). My dad had zero shame whatsoever selling them because they paid the bills, even if they weren’t the dish that got a write-up in the Star Tribune (though other things did).

Dad never went to school after the third grade back in China, but he did all his own shopping for the restaurant. He also did almost all the labor. He knew what he liked to make. But he also knew what paid. These were sometimes sharp and self-effacing observations for a man who would have loved to spread the joy of authentic, Hong Kong-style Cantonese lobster sauce to more people. But he also knew he was running a business. One of the things my dad asks me all the time about my mostly contingent-fee, plaintiff-side employment practice is whether I’ve landed any “cream cheese wontons” lately.

In my practice, “cream cheese wontons” are solid, contingent-fee wrongful termination cases that settle before litigation at a fair value because all the parties are accurately weighing risk and opportunity. Clients are thrilled with these results because I’ve helped them understand how such outcomes mitigate risk of loss (and worse), balance the strengths of their cases, and usually conclude efficiently.

Showing my clients that a case is a cream cheese wonton by speaking in a language they’ll understand has made my law practice easier. It’s also helped me streamline my business so I can focus on cases that I can do efficiently, consistently, and with less stress. That way, I reserve tons of mental bandwidth for other things—besides lawyering! We can’t be all things to all people as lawyers. Our well-being depends on it.

When dad’s restaurant went online-ordering-only in his final months before retirement as Covid hit, we eliminated half the menu to make life easier for him and reduce overhead.

Cream cheese wontons remained at the top of the page.

Lesson 2: Implicit Biases Are Inside All of Us—Check Them, Check Them, Check Them

I once sent a colleague to eat at my dad’s restaurant. By that time, my parents were long-divorced, and people knew the restaurant to be “my dad’s” (along with his new Vietnamese wife). But in a Modern Family-esque twist of human healing and forgiveness, my mom returned to the restaurant as a server about eight years after her divorce from my dad in 2001. Most of my colleagues didn’t know that my mother worked at the restaurant, nor did they know that my mother is white and that I am biracial.

The lawyer—who was and is a great mentor to me—had a singing report about the food. But he had one criticism: the service was a little less than stellar. He told me the waitress, “an older white woman,” just “didn’t seem to want to be there.”

I don’t blame him. It was a fair assumption that his colleague with the Chinese last name (me) had a Chinese mom. My mentor had no way of knowing. But even fair assumptions can be dead wrong, and relying on those assumptions can create embarrassing, awkward situations. I was too embarrassed to say anything and still haven’t. I’m also not all steamed up about it. It was simply a great reminder that we all carry our implicit biases with us.

I do, and I have to remind myself. When I pick up the phone to speak with a prospective new client, I hear accents from around the world. They each send various images and stereotypes dancing through my head, dreaming up images of exactly what kind of problem the person might have—some less fruitful matter-wise than others. That persnickety part of my gut, informed by implicit bias, is usually wrong. So, each time I pick up the phone, I commit myself to hear a person out fairly. I don’t want to miss a great opportunity to help someone who needs it. I don’t want to miss out on a cream cheese wonton.

Lesson 3: Delight in Your Privilege Rather than Despair Over Your Adversity

In high school, I was a little victim. Uncoordinated athletically, acne-ridden, angry over alcoholism in the family, and—the dollop of sweet and sour sauce on top—struggling with my sexual orientation.

And, like a good little victim, I let others know how upset I was, particularly when I was “forced” to work every Friday night and all day Saturday at the restaurant, rather than hang with friends or attend high school football games. One day, I had the gall to tell Pete and Cindy Decesare, two of the people who made our 70-seat dining room feel like the set of Cheers every Saturday afternoon, that I was about to “quit” and let my parents “figure out how to replace me” because I’d deserved “to just be a kid.”

Pete put his finger in my face after dropping a generous tip on the counter. He gave me another tip. He said I didn’t deserve anything. He also told me to look around and think really hard about the value of everything I’d learned getting to work at my family’s business. And he was right. By some miracle, I listened to Pete and started keeping tabs on the things I was getting out of this work.

A mere eighteen months into a “Big Law” career—and not loving it—it occurred to me that, as lawyers, we can pivot and thrive on our privilege. I went from feeling trapped to feeling endowed with valuable insights and experience. We atrophy by dwelling on adversity. (But get some help for that painful stuff. I did and I’m better able to use my gifts for it.) Taking the good with the bad, life became more navigable and fruitful the more I focused on my privileges rather than adversities. We all have both in spades. This outlook was instrumental in my first decade of practicing law. I now believe wholeheartedly what Pete told me that day: growing up in the restaurant gave me the best education I’ve ever received.

Ben Kwan represents employees in wrongful termination matters at Haller Kwan LLP in Minneapolis.