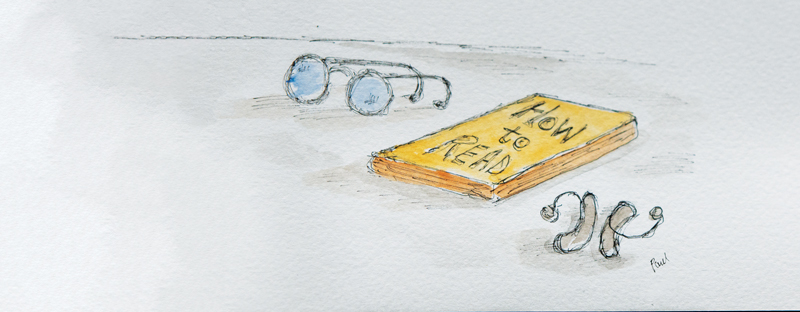

When I was in fourth grade I was shy and reserved. If you know me now, you might wonder how this was possible. But at the time, I was that kid in class who was always staring out into space, daydreaming. Probably not surprising, given that I also could not see the blackboard, but I kept that a secret. When the teacher wrote words or math problems on the board, I was lost. Eventually, it dawned on my teacher that I needed glasses. I did not want to wear glasses in elementary school for fear of being called Four Eyes. But, being extremely nearsighted, I needed what we call today an accommodation. With that accommodation, I could see.

We soon moved across Ohio. And while my eyesight improved with new glasses, I continued to struggle with reading. But I kept it a secret until the 6th grade, when my teacher asked each student to stand and read from our English textbook. When it was my turn, I read my part. My teacher said, “Paul, read it again.” So I read it again. This time she said, “Paul, slow down and read what is written on the page.” To which I replied, “I don’t care what is written, what I read is what it should say.” My teacher did not take my insolence lightly. It was what we in my family called “sass,” and you did not sass your teacher.

Instead, she sent me home with a note to my mother suggesting that I read out loud every night as a part of my homework. For the next few months, I would do my best to read to my mother. I was unaware at the time that I was struggling with undiagnosed dyslexia—which means that my brain periodically inverts letters and numbers. So I learned to read phonetically to make sense of it all. But after a few months, I was back to keeping my reading problems a secret (or so I thought). It worked pretty well until high school, when my math and reading deficiencies caught up with my grades (Cs and Ds).

In college, one of my first classes was creative writing. Being dyslexic, I liked the creative part. I was very creative in hiding my dyslexia and in coming up with ways to learn the material without reading a lot. My professor recognized that I had a problem and took the time to teach me grammar, spelling, and writing. By then I had learned to type my written submissions, which helped me succeed in college, seminary, and law school.

You may have guessed that not all my problems were solved. During one of my first months as a young associate at a new law firm, a partner called me into his office and asked me: “Did you send this letter out?” I said yes and he said read it. I read it. He asked: “Do you see anything wrong with it?” I said no, sensing that I must have missed something crucial. It was then he said, “You missed a ‘not’ in one conclusion. From now on all of your correspondence will need to be proofread by Becky.” I was so relieved! I thought he was going to fire me. Instead, he provided me with an accommodation.

Finally, I learned an important lesson. I had to admit to myself that I had a reading impairment and stop being afraid to seek help. It was actually quite liberating. With my secret out in the open, I could now ask for help so that my work product would be the best it could be.

Recently, I have noticed that my hearing is not as sharp as it once was. I find myself straining to hear my law students’ answers in class. While it is hard to admit that I need help with my hearing, I realize that I need another accommodation to help me continue to be the best lawyer I can be.

All around me, I find other lawyers and law students who face similar challenges in seeing, reading, learning, hearing, and mental health issues that demand accommodations and accessibility. This is a great example of the legal profession changing for the better. So, whether you need glasses, a hearing aid, or an accommodation for depression, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHA, dyslexia, or any other disability, know that you are not alone. In fact, your particular neurodiversity is a plus instead of a deficit.*

If you are neurodivergent, know you have a neurodiverse MSBA president. Let’s all partner to be a more diverse, equitable, and innovative bar association and legal profession. And remember to be kind, because the person next to you may have a secret.

* Teams that include both neurodivergent and neurotypical colleagues have the ability to look at problems from different angles, leverage the unique and more widely varied strengths of team members, and envision new possibilities. See Neurodiversity in the Workplace at https://nitw.org. Cognitively diverse teams have been shown to solve problems faster (https://hbr.org/2017/03/teams-solve-problems-faster-when-theyre-more-cognitively-diverse).

Paul Floyd is one of the founding partners of Wallen-Friedman & Floyd, PA, a business and litigation boutique law firm located in Minneapolis. Paul has been the president of the HCBA, HCBF, and the Minnesota Chapter of the Federal Bar Association. He lives with his wife, Donna, in Roseville, along with their two cats.