By Justice Paul Thissen

Statutes have many audiences. They communicate legislators’ values to their constituents or to more narrow interest groups. They communicate obligations and limitations imposed upon the people and private institutions who are the subject of the legislation, instructing them on what they can and cannot do. Statutes communicate directions—sometimes broad and sometimes detailed—to the executive branch of government on how to carry out various tasks of governing.

But one critically important audience for legislators and others involved in crafting statutes is judges. When people get into a dispute about what a statute means—about the scope and application of the obligations and limitations a statute imposes—it is judges who interpret it. And, of course, the best way to write for a particular audience is to put yourself in the shoes and the mind of that audience.

Keeping the judicial audience in mind is important because judges have, over centuries, built up a superstructure of rules for interpreting statutes. These rules are essentially assumptions about how legislators think when they are drafting, debating, and voting on statutes. Based on my experience as a member of the Minnesota Legislature for 16 years and as a judge for nearly six years, judges’ perceptions about how the Legislature operates differ in fundamental ways from how the Legislature operates in real life.

Said more plainly, people involved in crafting statutes presumably want the statute to be applied in the way they intended. And so it is in a legislator’s self-interest to anticipate, when writing a statute, how a judge will understand what the legislator was trying to accomplish. That way the legislator can minimize the risk of a judge interpreting the statute in a different and unexpected way. In this article, I hope to provide practical tips for people involved in the process of drafting statutes so they can maximize the odds that judges will interpret and apply statutes as their drafters intended.

I want to be clear that this is not a one-way street. Judges and lawyers also have an obligation to learn more about how the legislative process actually works. Indeed, I teach an entire law school class with that goal in mind. But that is a subject for a different article.

Thinking like a lawyer

Different professions are taught to look at the world and approach problems in different ways. Our perspectives and analytic methods can become so ingrained over time that it is difficult to approach a problem using a different lens. Indeed, one forgets that different lenses even exist. That is as true for judges as for any profession.

To anticipate how judges will interpret a statute, consider the way lawyers think. Lawyers are taught to systematize and categorize—to create hierarchies of ideas and principles. Moreover, lawyers hate to leave stray things lying about. They like to fit concepts, words, ideas, types of conduct, and more into boxes and they like to have a box where everything can be placed.

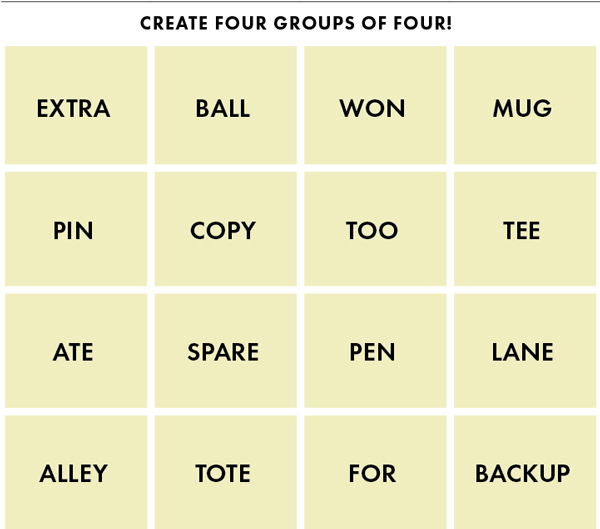

A simple example of this is the New York Times Connections game. In Connections, a player is given 16 words and the goal is to fit groups of four words into four categories that have a common theme or characteristic. For example:

Let’s start with the word “tee.” Does that word fit with the words ball, pin, and won (things related to the game of golf) or with mug, tote, and pen (things given as merch at a bar association conference, i.e., a tee shirt). This is a perfect game for lawyers because it requires the player to figure out the theme or characteristic that connects words, to fit each word into the correct category, and to leave no word without a category.

This closely resembles the thought process a judge goes through—guided by the canons of construction—when interpreting a statute. Reading the statutes you are drafting, debating, and voting on from this perspective may open your eyes to ways that a statute could prove ambiguous to a judge. Is a tee the thing you drive a golf ball from or a thing you wear?

Define your terms

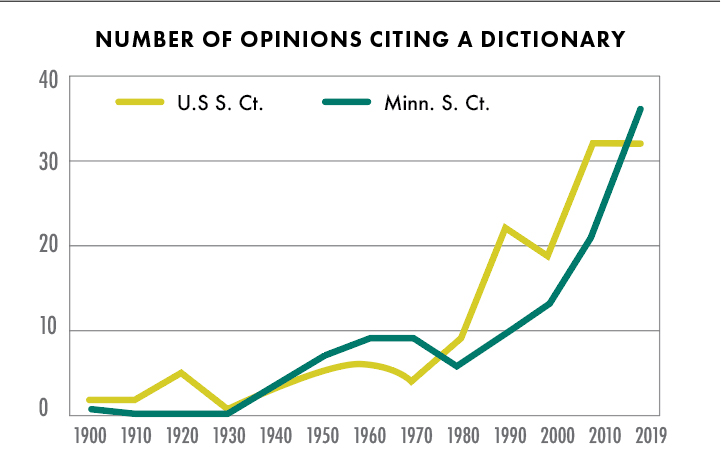

Judges love to look at dictionaries to help them understand what words in a statute mean. I have over a dozen different dictionaries sitting on my shelf within easy reach as I write this, and, more importantly, as I write my opinions. And I am not even that big a fan of dictionaries. Here is a chart that former Justice David Lillehaug put together a few years ago:

For reference, the Minnesota Supreme Court, like the U.S. Supreme Court, typically writes fewer than 100 opinions per year. Judges on these courts, in other words, cite dictionaries in roughly a third of their opinions, and that percentage is rising. In contrast, I never saw a legislator in committee or on the floor consulting a dictionary when trying to understand what a statute means or deciding how to vote on a bill or amendment.

The reality is that dictionaries themselves are often sources of ambiguity and contradiction, both within a single dictionary and between different dictionaries. Sometimes a single dictionary will include a dozen or more inconsistent definitions for the same word.1 Thus, a judge will often have considerable discretion in choosing which of several dictionary meanings to adopt when interpreting the meaning of the statute. For legislators who want to keep some control over the application of the laws they passed, that is a problem.

For example, the Minnesota Supreme Court was once asked to interpret Minn. Stat. §609.375 (2012), which provided: “Whoever is legally obligated to provide care and support to a spouse or child… and knowingly omits and fails to do so is guilty of a misdemeanor….”2 A father convicted under the statute for not paying child support appealed, arguing that “care” and “support” were two separate obligations.3 Because he provided “care” (defined in dictionaries as “watchful oversight, charge or supervision”) to his children, he claimed that he had not violated the statute—even though he admitted he had not provided monetary “support” to his children.4 Although one justice reasoned that “care and support” was a single concept that required payment of financial support,5 the Court agreed with the father and reversed his conviction.6 The majority reasoned that the Legislature must have intended to give “care” a meaning distinct from “support,” because otherwise it would not have used both terms.

There is an interesting postscript to this decision. Within a year of the decision, the Legislature changed the phrase “care and support” to “court-ordered support.”7

But there is good news for legislators who want to avoid confusion like this in future cases. Judges adhere to a simple rule that says if the Legislature defines a term used in a statute, judges are bound to follow it, even if dictionaries would point to a different meaning.8 Take advantage of that rule. If you are drafting a statute and have a particular meaning of a word in mind, put that definition in the statute.

Use one word when one word will do

Judges like to apply a rule called the surplusage canon. It states that legislators intend that every word in a law must be given meaning and effect and that no word in a statute should be given a meaning that causes it to duplicate the meaning of another word in the statute. The practical impact of this rule is that judges often go searching for multiple meanings of different words in a series, even if the legislators who drafted and voted for the bill harbored no such intent.

I have my doubts about whether this assumption reflects how actual legislators think and act. In a survey of Minnesota legislators conducted a few years ago, legislators reported unfamiliarity with the surplusage canon and said that redundant words and words with overlapping meaning are often used in a statute to make certain that a single meaning is clear; in other words, legislators use a “belt and suspenders” approach.9 But that doubt aside, the surplusage canon is commonly used.

So what should legislators who wants some control over the laws they are drafting do? Look for strings of nouns or verbs in a statute and think hard about how you want them to be understood—as separate and distinct concepts or as redundant or mutually reinforcing terms?—and choose your language accordingly. When in doubt, err on the side of using one word if that will get the job done.

Beware of lists

Lists are a common feature of statutes and also a common source of dispute and confusion. Consequently, courts have developed several rules for understanding lists.

For instance, courts use the associated words canon,10 which says that words grouped in a list should be given related meanings. (A perfect example of the Connections game applied to statutory interpretation.) Sounds like common sense, right?

Let’s take an example: Suppose the Legislature passed a law that says, “A person must carry explosives into a mine in a canister or container.” Later, someone carried an explosive into a mine in a cloth bag and a tragedy ensued. Is this a violation of the law?

One person might answer “No, a cloth bag is a container and the statutory text says ‘container.’” Another person, applying the associated words canon, might say, “Hold on, a cloth bag is nothing like a canister. This statute only authorized people to use containers with a strength like that of a canister to carry explosives into mines.” This is not so easy to decide.

Notably, legislators’ intuitions on the topic are split. In the survey, one-third thought that a cloth bag was a “container” for purposes of the statute and two-thirds thought it was not.

Courts also use the ejusdem generis canon when faced with a statutory list.11 This canon applies to lists that start by identifying two or more specific things and then end with a general catch-all phrase. The ejusdem generis canon instructs courts to apply the general catch-all only to things of the same general kind or class as the things specifically mentioned.

For instance, if a statute said that a “tax credit may be used to support the manufacture of automobiles, trucks, tractors, motorcycles, and other motor-powered vehicles,” should a judge conclude that a manufacturer of airplanes is eligible for the tax credit? An airplane is a motor-powered vehicle by any ordinary understanding of that phrase, but an airplane is not used to travel on land like automobiles, trucks, tractors, and motorcycles. Did the Legislature intend the phrase “other motor-powered vehicle” to be read literally or more narrowly?

A legislator who wants to control how a statute is applied in the wild should bear these two canons of construction in mind and avoid using lists—especially non-exclusive lists of examples—where possible. If you mean that explosives should only be carried in containers of a certain strength, say that. If you mean that the tax credit should apply to all motor-powered vehicles wherever they are used, then just use the words “motor-powered vehicle” without a list of examples. If you mean to limit the tax credit to vehicles used on land, say that.

Pay attention to how courts have understood words in other, related statutes

The Minnesota Supreme Court had a case where a person was found sitting in another person’s vehicle but had not moved it anywhere.12 The person was charged with theft of a motor vehicle in violation of a statute that provided that a person who “takes or drives a motor vehicle without the consent of the owner… knowing or having reason to know that the owner… did not give consent” commits criminal theft. Minn. Stat. §609.152, subd. 2(a) (2016). Was the person properly found guilty because he “took” the car?

The Court found dictionary definitions of “takes” unhelpful because some definitions suggested that to take something requires some motion or movement of the thing while other definitions suggested that a person takes something when the person exercises dominion over it.13 Instead, the Court looked to a prior case14 where it had interpreted the word “takes” in a tangentially related statute—the robbery statute—which provided:

Whoever, having knowledge of not being entitled thereto, takes personal property from the person or in the presence of another and uses or threatens the imminent use of force against any person to overcome the person’s resistance or powers of resistance to, or to compel acquiescence in, the taking or carrying away of the property is guilty of robbery….

Minn. Stat. §609.24 (2016). In the prior case, the Court held that a person “takes” something, for purposes of robbery, when that person exercises dominion over it.15 Accepting that meaning as a definitive judicial interpretation of the word “takes” in the context of theft-related statutes, the Court held that simply sitting in a car without moving it constitutes theft of a vehicle.16

What is the lesson for legislators and others drafting statutes? Ask the people sponsoring and drafting the bill or legislative staff how courts in the past have defined terms in related areas of law—both related statutes and related common (judge-made) law. If that is the meaning intended in the new statute, great. If not, use a different word or (once again) expressly define in the statute how you want the term to be understood.

Consider the atypical situation

Legislators have a difficult job. Often, they are trying to solve a very specific problem but have to write a statute that applies generally. Of course, being human, legislators and those helping them draft statutes cannot anticipate every future circumstance where their general law may be applied. But taking a bit of time to consider the atypical situation can help head off future statutory interpretation problems.

For instance, the Minnesota Supreme Court faced a dispute between a condo association and the developers and builders of the condo building over structural problems that affected the entire building (as opposed to a single unit).17 The Court had to decide the date on which the 10-year statute of repose for breach of warranty started to run.18

The statute directed that no action for a breach of warranty could be brought more than 10 years after the “warranty date.”19 The statute defined “warranty date” as “the date of the initial vendee’s first occupancy of the dwelling.”20 It defined “dwelling” as a “new building, not previously occupied, constructed for the purpose of habitation….”21 “Building” was not defined. Finally, the statute defined “initial vendee” as “[a] person who first contracts to purchase a dwelling from a vendor for the purpose of habitation….”22

For a single-family home (which presumably is what legislators had in mind when drafting and debating the statute), determining the warranty date is easy: It’s the date when the first purchaser of a newly constructed home occupies the new home. But as the Court concluded, determining the warranty date for a condo building—which has several different dwellings within a single building—is not so clear cut, because the initial occupation of each condo unit might occur at a different time.

The builder and developer argued that there must a single date for the entire building because the statute of repose runs from the date of the first occupancy of the “dwelling,” which is defined as a building. The condo owners countered that the builder’s and developer’s interpretation ignores the definition of “initial vendee.” In a condo, no one buys the entire building to live in it—there are several separate units of habitation. Under the builder’s interpretation, there can never be an initial vendee at all because no one buys the entire building to live in it.

The Court ultimately concluded the language was ambiguous and turned to other clues, like legislative history, to resolve the dispute. But for purposes of this article, the point is this: Had legislators stepped back for a moment and thought about how the statute of repose provision would play out for dwellings other than single-family homes, the entire dispute could have been avoided.

The lesson—which is easily stated and harder to implement—is to consider those other, less obvious, circumstances where the law you are drafting may apply. If you are legislating about housing, take a moment to think about all the different types of housing that exist. If you are regulating restaurants, think about the different types of restaurants that exist and make sure the language is sensible when applied to each type. Sometimes that will require more nuanced, specifically crafted bill language.

Read bill language that is not struck-through or underlined

One of the most common sources of statutory confusion arises when statutes are amended. As anyone who has spent time reading legislative bills and amendments knows, new statutory language is underlined and language to be deleted is struck-through. I know from experience that legislators’ eyes are drawn to the underlined and struck-through provisions and the debate, for good reason, is often focused there. It is important, however, not to neglect the rest of the language because it often happens that the amended portions—while clear in that narrow context—can also change the meaning (or at least raise doubts about the meaning) of other, existing parts of the law or vice versa.

Here’s an example: The Minnesota Supreme Court faced the question of what the state had to prove to convict a person for first-degree criminal sexual conduct under Minn. Stat. §609.342, subd. 1(h) (2018).23 The statute was structured in a common way starting with a general description of the fundamentals of the crime and then listing a series of additional specific circumstances, one of which must be proved. It provided:

Subdivision 1. Crime defined. A person who engages in sexual penetration with another person, or in sexual contact with a person under 13 years of age as defined in section 609.341, subdivision 11, paragraph (c), is guilty of criminal sexual conduct in the first degree if any of the following circumstances exists: ...

(h) the actor has a significant relationship to the complainant, the complainant was under 16 years of age at the time of the sexual penetration, and:

(i) the actor or an accomplice used force or coercion to accomplish the penetration;

(ii) the complainant suffered personal injury; or

(iii) the sexual abuse involved multiple acts committed over an extended period of time.

Id., subd. 1 (2018) (emphasis added).

In the initial general description of the crime, then, the statute allowed for two types of conduct to constitute first-degree criminal sexual conduct: sexual penetration or sexual contact. On the other hand, the specific circumstance set forth in subpart (h) required that certain conditions existed “at the time of the sexual penetration.” The Court was left to resolve the question: is subpart (h) limited to sexual penetration?

The Court answered that question “Yes.”24 But more importantly for our purposes, how did that confusion come to be? The statutory history holds the answer.

The language of subdivision 1(h) originally appeared in a different statute from the general criminal sexual conduct statute: the intrafamilial sexual abuse statute. The intrafamilial statute made it a first-degree crime to engage in sexual penetration with a person with whom you have a familial relationship and treated sexual contact short of penetration with the same person as a lesser crime.25 The general criminal sexual conduct law, however, treated sexual contact as well as sexual penetration with younger children outside the family as a serious first-degree crime.26

In 1985, the provisions of the intrafamilial sexual abuse statute were merged verbatim into the general criminal sexual conduct statute as subdivision 1(h).27 That subdivision repeated, in a specific circumstance, the “penetration” element included in the statute’s general definition.28 Maybe no one caught the redundancy because the language in the general definition was not underlined. Or maybe they saw the redundancy and did not care.

In 1994, the general introductory portion of the statute was amended to expand first-degree criminal sexual conduct to include not just sexual penetration, but also sexual contact with someone under 13 years of age.29 The bill made no changes to any of the specific circumstances identified in the bill, so no underlines or strike-throughs appeared in that part of the bill, which included the redundant penetration language in subdivision 1(h).30 And ultimately, the penetration language in subdivision 1(h) (which did not include sexual contact) resulted in the confusion we faced decades later.

The lesson is that context matters. When reviewing bill language, do not just focus on what is new and what is being deleted. Rather, read the entire provision that is being amended and make sure the changed language fits with the existing language.

Mind the modifiers

Minnesota’s peeping statute provides as follows:

A person is guilty of a gross misdemeanor who:

(1) enters upon another’s property;

(2) surreptitiously gazes, stares, or peeps in the window or any other aperture of a house or place of dwelling of another; and

(3) does so with the intent to intrude upon or interfere with the privacy of a member of the household.31

After reading this statute, ask yourself: Does the state have to prove that the defendant had the requisite intent when the defendant entered the property and when the defendant gazed, stared, or peeped? Or is it enough to prove that the defendant had the requisite intent only when the defendant gazed, stared, or peeped?32

This type of question is among the most common sources of statutory interpretation confusion that Minnesota courts face—and it is an especially acute problem in criminal cases where mens rea is at issue. Does an intent or knowledge requirement apply to all the elements of a crime or just to some?

To resolve this question, courts often turn to grammatical rules that no judge wants to apply and no legislator I know ever considered.33 Should we apply the series qualifier rule, which directs that when there is a straightforward, parallel construction that involves all nouns or verbs in a series, a qualifier normally applies to the entire series? Or should we apply the last antecedent rule, which points in the opposite direction by telling us that a limiting phrase ordinarily modifies only the noun or phrase that it immediately follows? What should we make of commas and semicolons?

Please don’t make judges undertake such exercises in sentence diagraming—exercises that we would rather leave in the mists of fifth-grade English class. Instead, pay close attention to modifying words and phrases. If there are multiple elements or factors set forth in a statute, use more words, if necessary, even to the point of repeating the modifier for each element or factor to which it applies.

Use express language to change the common law or create a private right of action

Another common tool judges use to resolve statutory interpretation disputes are strict-construction presumptions judges makes that the Legislature does not intend to do certain things unless it has expressly declared an intent to do so or such an intent is otherwise “clearly indicated” by the language of the statute. For instance, if there is a dispute over whether a statute changed the prior common law, courts presume that the Legislature did not intend such a change and will construe the statute narrowly.34 The rule also applies when there is a question of whether a statute creates a private right of action; courts presume the Legislature did not.35

Determining whether the Legislature “clearly indicated” an intent to abrogate the common law or to create a private right of action—when the statutory language does not expressly do so—leaves substantial room for judges to maneuver. For instance, the Minnesota Supreme Court has said that “our presumptions regarding the [continuation of the] common law cannot undermine legislative intent. Although we have said that we construe statutes in abrogation of the common law ‘strictly,’ we do not construe them ‘so narrowly’ that ‘we disregard the Legislature’s intent.’”36 That standard is not a model of precision. Accordingly, judges may and do interpret a statute more or less broadly than the Legislature intended—and all without ever looking to other indications of legislative intent like legislative history or the purpose of the statute.

Legislators who do not wish to leave to a judge’s discretion the question of whether a statute abrogated the common law or created a private right of action have an easy remedy: If you want to get rid of a common law rule or create a private right of action, say so in the statute.37 And if you do not want to create a private right of action or to abrogate common law rights and remedies (which might parallel those created in the statute), say so.

Statements of legislative purpose and public policy are a legislator’s friend

This may be the most controversial tip in this article. The general consensus among Minnesota legislators and others at the Capitol long has been that statements of legislative purpose and statements of public policy are a mistake. I beg to differ. Statements of legislative purpose and statements of public policy protect a statute from erroneous judicial interpretation and give the Legislature more control over statutory meaning.

Here is the reality: Despite all best efforts, some statutes will be ambiguous. And what do judges do in that situation? They try to divine the Legislature’s purpose in enacting the statute.38 That, of course, gives judges flexibility to choose the public policy purpose that the judge prefers. Moreover, courts have developed all sorts of rules and presumptions to help in that project—rules and presumptions that may have nothing to do with the purpose of the Legislature when it enacted a particular statute. For example, judges say they favor the public interest as against any private interest (even for statutes that are intended to serve a private interest).39 Remedial statutes are construed liberally in favor of the remedial purpose (which begs the questions: what is a remedial statute, and how does one determine which of several potential remedial purposes is to be favored?).40 Tax laws are to be construed in favor of the taxpayer.41

Statements of purpose and public policy provide clear textual guidance to courts in a way that limits judicial discretion. For instance, the Minnesota Workers Compensation Act was enacted to balance the interests of employers and employees when a worker is injured on the job. In light of that balance, the statute expressly provides:

It is the intent of the legislature that chapter 176 be interpreted so as to assure the quick and efficient delivery of indemnity and medical benefits to injured workers at a reasonable cost to the employers who are subject to the provisions of this chapter. It is the specific intent of the legislature that workers’ compensation cases shall be decided on their merits and that the common law rule of “liberal construction” based on the supposed “remedial” basis of workers’ compensation legislation shall not apply in such cases. The workers’ compensation system in Minnesota is based on a mutual renunciation of common law rights and defenses by employers and employees alike.... Accordingly, the legislature hereby declares that the workers’ compensation laws are not remedial in any sense and are not to be given a broad liberal construction in favor of the claimant or employee on the one hand, nor are the rights and interests of the employer to be favored over those of the employee on the other hand.42

This language leaves little room for judges to impose their policy preferences in favor of workers or employers. Courts know what the Legislature’s priorities are.

The Minnesota Human Rights Act also provides statutory guidance to judges and lawyers. Minn. Stat. §363A.02 currently states:

Subdivision 1. Freedom from discrimination

(a) It is the public policy of this state to secure for persons in this state, freedom from discrimination:

(1) in employment because of race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, gender identity, marital status, disability, status with regard to public assistance, sexual orientation, familial status, and age; (2) in housing and real property because of race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, gender identity, marital status, disability, status with regard to public assistance, sexual orientation, and familial status…

(b) Such discrimination threatens the rights and privileges of the inhabitants of this state and menaces the institutions and foundations of democracy. It is also the public policy of this state to protect all persons from wholly unfounded charges of discrimination. Nothing in this chapter shall be interpreted as restricting the implementation of positive action programs to combat discrimination.

Subdivision 2. Civil right.

The opportunity to obtain employment, housing, and other real estate, and full and equal utilization of public accommodations, public services, and educational institutions without such discrimination as is prohibited by this chapter is hereby recognized as and declared to be a civil right.43

This language provides a lot of useful information to judges interpreting the Human Rights Act. It tells us the purpose of the prohibitions on discrimination is both to protect individuals and to preserve our democratic institutions. It instructs that the Legislature did not intend the statute to outlaw consideration of race, religion, sex, disability, or other identified characteristics in an effort to address disparities based on historical or institutional discrimination and prejudice. And in another provision of the Human Rights Act, the Legislature expressly declared that the provisions of the statute “shall be construed liberally for the accomplishment of the purposes thereof.”44

While each of these public policy positions concerning Minnesota’s workers compensation and human rights statutes may be reasonably debated, these statements of purpose ensure that the branch of government best and most properly situated to make those decisions—the Legislature—remains in control.

Conclusion

Better communication among the three branches of government is critical to providing Minnesotans with the humane, effective, and efficient government they deserve. Better communication is most likely when each of the branches has a better understanding of how the other branches operate. Judges and lawyers would be well served to pay more attention to how legislators and agencies do their respective jobs. Likewise, legislators and others who work in the legislative branch will serve their constituents better if they understand how the judges who will inevitably be reviewing their work go about their jobs.

Legislators are elected to do a hard job—solving problems facing Minnesotans by balancing varied competing values and public policy interests. The Legislature has the institutional tools to best accomplish that work. These tips are offered to help legislators and those who work with them accomplish their goals. Hopefully these tips will also help legislators think more carefully about what they are, in fact, trying to accomplish when drafting and enacting statutes.

Paul Thissen is an associate justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court. Thissen served in the Minnesota House of Representatives from 2003-2018, including as speaker of the House, while maintaining a litigation and transactional practice in the Twin Cities.

Notes

1 See State v. Thonesavanh, 904 N.W.2d 432, 436 (Minn. 2017) (noting that The American Heritage Dictionary defines the word “takes” in over 80 ways—including 61 definitions when the word is used as a transitive verb—and that Webster’s Third New International Dictionary has over 90 definitions of the word “take”).

2 State v. Nelson, 842 N.W.2d 433, 436 (Minn. 2014) (quoting Minn. Stat. §609.375, subd. 1) (emphasis added).

3 Id.

4 Id. at 436–37.

5 Id. at 444 (Dietzen, J., dissenting).

6 Id. at 444. Three justices dissented from the case; Justice Dietzen reasoned that “care and support” referred specifically to monetary child support. Id. (Dietzen, J., dissenting). Justice Lillehaug and Chief Justice Gildea would have affirmed on different grounds, without reaching the issue of whether “care” and “support” were distinct elements. Id. at 451–52 (Lillehaug, J., dissenting).

7 Act of May 12, 2014, ch. 242, §1, 2014 Minn. Laws 1 (codified as amended at Minn. Stat. §609.375 (2022)).

8 State v. Fugalli, 967 N.W.2d 74, 77 (Minn. 2021).

9 The survey was conducted from April to June 2019 as a senior project by Ethan Less. I served as an advisor to Mr. Less on the project. Mr. Less provided the survey to every member of the Minnesota House and Minnesota Senate. The response rate was 15%. Mr. Less also conducted follow-up narrative interviews with several legislators. The survey results are available from the author. The survey was inspired by the excellent and illuminating work of Abbe Gluck and Lisa Schultz Bressman. See Abbe R. Gluck & Lisa Schultz Bressman, Statutory Interpretation from the Inside – An Empirical Study of Congressional Drafting, Delegation, and the Canons: Part 1, 65 Stan. L. Rev. 901 (2013).

10 See, e.g., State v. Friese, 959 N.W.2d 205, 213 (Minn. 2021).

11 See, e.g., State v. Sanschagrin, 952 N.W.2d 620, 627 (Minn. 2020).

12 State v. Thonesavanh, 904 N.W.2d 432, 434 (Minn. 2017).

13 Id. at 436.

14 Id. at 438 (citing State v. Solomon, 359 N.W.2d 19, 21 (Minn. 1984)).

15 Solomon, 359 N.W.2d at 21.

16 Thonesavanh, 904 N.W.2d at 438.

17 Village Lofts at St. Anthony Falls Ass’n v. Housing Partners III-Lofts, LLC, 937 N.W.2d 430, 435 (Minn. 2020).

18 Id. at 442.

19 Minn. Stat. §541.051, subds. 1, 4 (2018).

20 Minn. Stat. §327A.01, subd. 8 (2018).

21 Minn. Stat. §327A.01, subd. 3 (2018).

22 Minn. Stat. §327A.01, subd. 4 (2018).

23 State v. Ortega-Rodriguez, 920 N.W.2d 642, 645 (Minn. 2018).

24 Id. at 647.

25 Minn. Stat. §§609.3641–.3644 (1984).

26 Minn. Stat. §§609.342–.345 (1984).

27 Act of May 31, 1985, ch. 286, §15, 1985 Minn. Laws 1299, 1306 (codified at Minn. Stat. §609.342 (1985)).

28 Id.

29 Act of May 10, 1994, ch. 636, art. 2, § 34, 1994 Minn. Laws 2170, 2206 (codified at Minn. Stat. §609.342 (1994)).

30 Id.

31 Minn. Stat. §609.746 (2022)

32 See State v. Pakhnyuk, 926 N.W.2d 914, 927 (Minn. 2019).

33 See, e.g., State v. Galvan-Contreras, 980 N.W.2d 578, 584 (Minn. 2022).

34 Jepsen as Trustee for Dean v. County of Pope, 966 N.W.2d 472, 484 (Minn. 2021).

35 Becker v. Mayo Found., 737 N.W.2d 200, 207 (Minn. 2007).

36 Jepsen, 966 N.W.2d at 484 (quoting Swanson v. Brewster, 784 N.W.2d 264, 280 (Minn. 2010)).

37 See, e.g., Minn. Stat. §325G.207, subd. 3 (2022) (expressly creating a private right of action for violations of assistive device warranty statute).

38 Indeed, the Legislature has directed the courts to do just that in Minn. Stat. §645.16 (2022).

39 See Minn. Stat. §645.17(5) (2022). Of course, as any legislator knows, there are often multiple and sometimes competing public interests implicated in a statute.

40 See S.M. Hentges & Sons, Inc. v. Mensing, 777 N.W.2d 228, 232 (Minn. 2010).

41 Charles W. Sexton Co. v. Hatfield, 116 N.W.2d 574, 580 (Minn. 1962).

42 Minn. Stat. §176.001 (2022).

43 Act of May 19, 2023, ch. 52, art. 19, §45, 2023 Minn. Laws 1, 327 (amending Minn. Stat. § 363A.02 (2022)).

44 Minn. Stat. §363A.04 (2022)).