By Paul M. Floyd

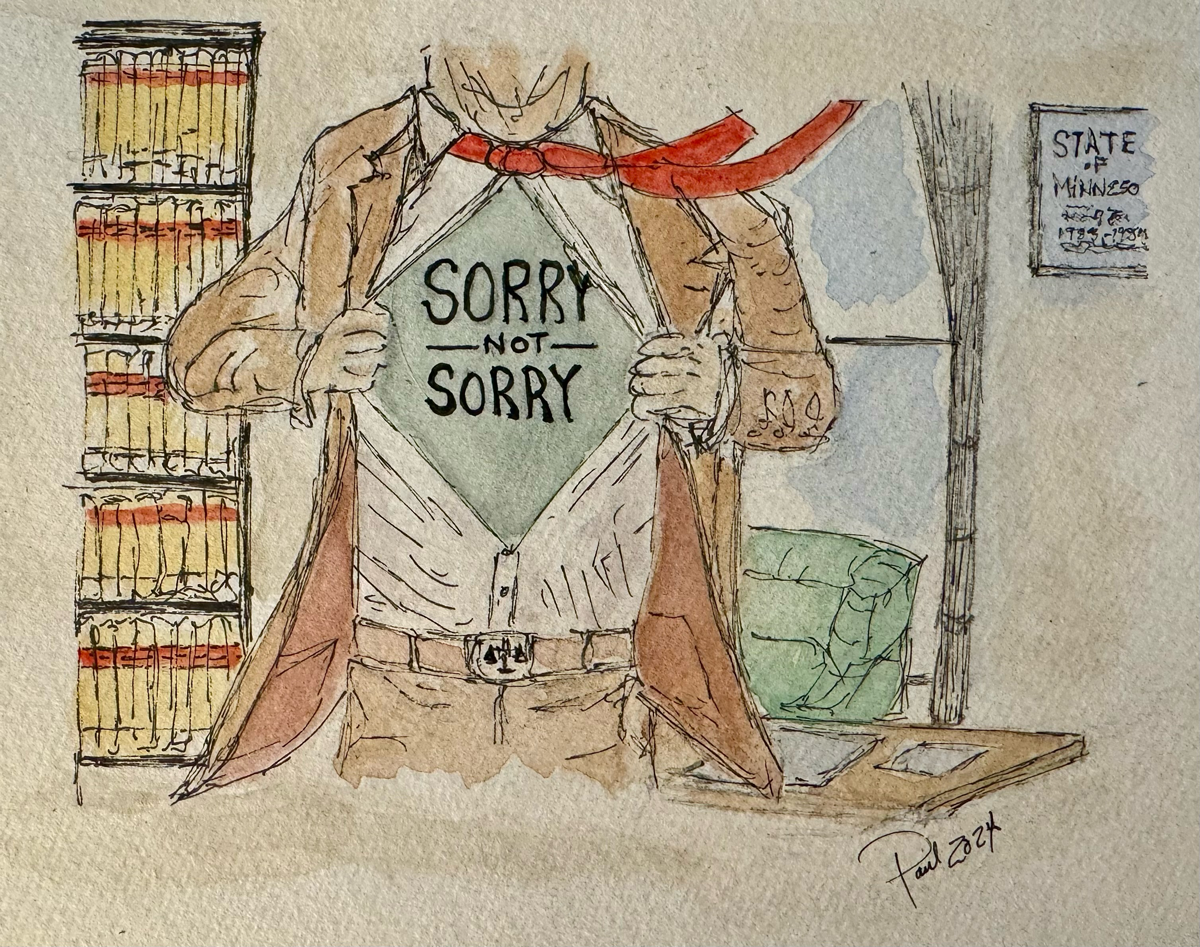

Much has been written and said about the lack of civility in the practice of law. But sometimes what appears to be a lack of civility is really a clash of conversational styles. Recognizing the difference can avoid unnecessary conflict and cultivate an appreciation for the upbringing and cultural background of the other person.

Here in Minnesota, locals are known for their “Minnesota Nice” manner of communicating—which, according to the 1994 book Minnesota Nice: A Transplant’s Guide to Surviving and Thriving in Minnesota, boils down to seven characteristics: polite friendliness; aversion to confrontation; not wanting to intrude; emotional restraint; resistance to change; passive aggressiveness; and understatement.

Minnesota Nice can be confusing and even frustrating for those who weren’t raised in Minnesota. This is particularly true for law students, lawyers, and their families when they have recently moved to the area. Coming from Ohio, I had no experience with the concept until I arrived here for graduate school. In meetings and small group discussions, I found that others had a tendency to avoid direct confrontation and to use euphemisms rather than address an issue head-on. For example, people would say “isn’t that interesting” when they really meant that something was unappealing or even disgusting. Minnesota Nice goes beyond just avoiding confrontations; it is also a common means of indirect communication.

In Minnesota, interrupting another person and talking over them may be perceived as disrespectful and demonstrating a lack of civility, even to the point of feeling bullied. However, to a transplanted East Coaster, interruptions are simply an accepted way to keep the conversation moving along. Native Minnesotans expect conversations to include “positive lag time,” a delay of a few seconds between the end of one person’s sentence and the start of the other person’s sentence. To an East Coaster [yawn], these seconds can feel like an eternity. Instead, they may be used to a “negative lag time” of two to three seconds. In other words, they start talking before the other person finishes their thought, and expect that the other person will talk over the end of their sentences as well. A Minnesotan might find this rude but, in fact, it is the opposite of being disrespectful because it means that the listener is actively participating in the conversation and cares enough to enter into a dialogue with the speaker.

Of course, there are times when a lawyer is required to interrupt another person as they are speaking, such as when they have to raise objections in depositions and in court. It is also entirely appropriate for a judge to interrupt a witness’s testimony or a lawyer’s argument in court, particularly when the speaker blatantly disregards the judge’s instructions. In these situations, Minnesota Nice needs to give way to straightforwardness in an attempt to control the situation. A lawyer who cannot bridge that gap may be perceived as timid or lacking competence. But as with so many things, context matters. Carrying over cross-examination techniques into personal relationships has soured more than one friendship or marriage.

For most lawyers, the way we communicate in everyday situations, not just in court or during depositions, is crucial. This includes our interactions with business partners, staff, clients, and others. Our communication styles are significantly influenced by our upbringing and the prevalent communication norms of our culture. Additionally, family and community expectations shape our communication habits, teaching us when and how to engage effectively. It’s challenging to adopt beneficial communication strategies and discard ineffective ones. But just as in many aspects of relationship management, possessing a diverse set of communication tools (that include knowing when and how to speak and when to listen) is essential for achieving professional and personal success.

As a colleague reminded me years ago after leaving a heated board meeting, sometimes we are clueless about how we come across in interacting with others, especially in a more public setting. He said, “You don’t know what you don’t know.” Even the most introspective of us may have blind spots. Consider asking a close friend or someone whose opinion you trust, “How did I do?” “Was I too pushy?” “Did I go too far or not far enough in making my point?” Then listen, and follow up with “How could I have handled that better?” And if you want to take it to the next level, ask yourself, “What is it about my personality that could not let it go?” The answer you come up with may really help you understand how to communicate more effectively in the future.

Of course, even if you come from a culture where interrupting during conversations is normal, it’s important to consider whether this style is appropriate for your audience. Interruptions can disrupt and even halt a conversation entirely. It is not enough to understand what your own style is; it is as important or more important to be able to adapt to the communication style of the person you’re speaking with. So when you encounter a style that’s vastly different from your own, try to be patient and understanding. They may feel the same about your way of communicating.

Paul M. Floyd is one of the founding partners of Wallen-Friedman & Floyd, PA, a business and litigation boutique law firm located in Minneapolis. Paul has been the president of the HCBA, HCBF, and the Minnesota Chapter of the Federal Bar Association. He lives with his wife, Donna, in Roseville, along with their two cats.

Paul M. Floyd is one of the founding partners of Wallen-Friedman & Floyd, PA, a business and litigation boutique law firm located in Minneapolis. Paul has been the president of the HCBA, HCBF, and the Minnesota Chapter of the Federal Bar Association. He lives with his wife, Donna, in Roseville, along with their two cats.