Two recent Supreme Court cases shift the emphasis in Minnesota divorce law

By m boulette, Seungwon Chung, and Abby Sunberg

As divorce lawyers, we can’t make many promises. Family court outcomes are notoriously uncertain and the classic lawyerly “it depends” is often the only answer. But there was at least one promise we could always make: By the time this is over, you’ll be divorced. Once and for all. But after recent cases from the Minnesota Supreme Court, even that answer may now depend.

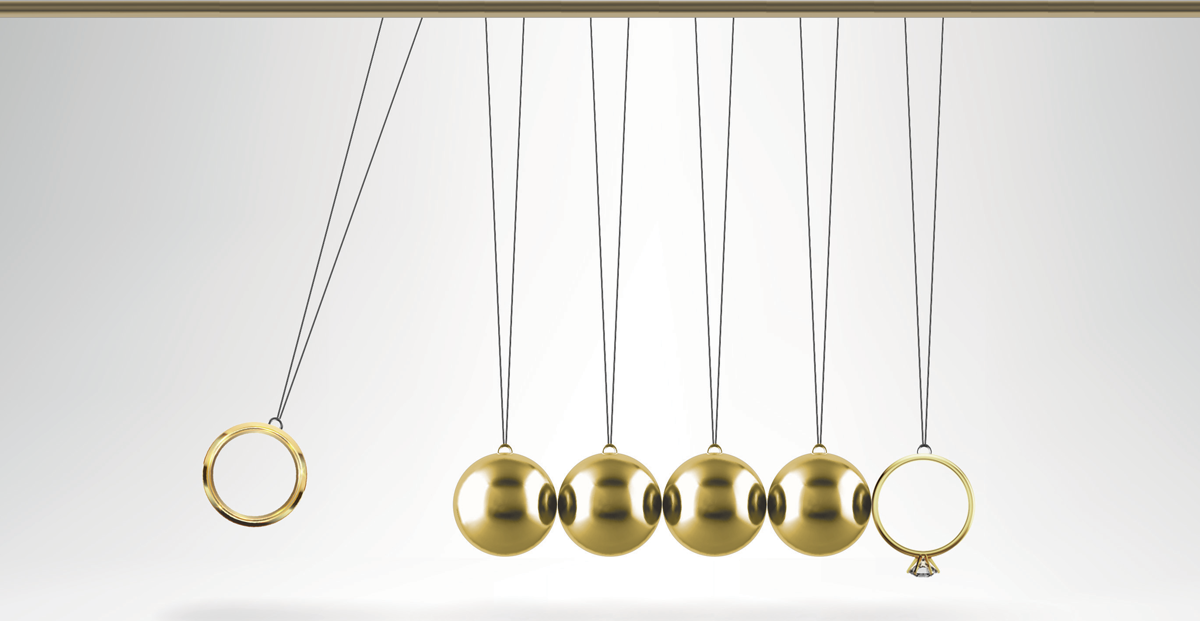

In 2022, the Court decided two cases that make finality less certain for divorcing parties—Bender v. Bernhard1 and Pooley v. Pooley.2 In both, the Minnesota Supreme Court prioritized a more equitable approach to relief in divorce over the traditional principles of finality. Now, Minnesota family law practitioners must grapple with Bender and Pooley’s consequences, finding ways to firmly close the door once more or at least mitigate the risks of leaving it slightly ajar.

With this newfound uncertainty, what’s a lawyer to do? We’ve attempted to boil down 30 years of history into three basic chapters. In the first, we explain how the initial approach to post-decree relief—granting such relief when equity required—left couples at risk of a life spent in litigation purgatory. In the second, we describe the Legislature’s solution—Section 518.145, subd. 2—and the Court’s prior commitment to limiting grounds for relief in favor of finality. And in the most recent, we illustrate the road back to equity in Bender and Pooley. We then end with some guidance for lawyers trying to navigate this new world.

Chapter 1: Inherent authority bends toward equity.

When it comes to finality, divorces have always been different. On one hand, ex-spouses can always return to change issues like child custody, support, and maintenance,3 res judicata be damned.4 On the other hand, the civil rules traditionally omitted divorce decrees from the general rules on post-judgment relief.5 As a result, parties could only obtain relief from a divorce decree by resorting to the inherent power of courts.6

But that inherent authority was limited. While civil rules provided a broad array of grounds for relief from final judgment,7 courts “ha[d] no authority to open up a divorce decree” unless there was a showing of “fraud on the court and the administration of justice.”8

For such a simple rule, courts struggled mightily to apply it, as more and more cases arose that cried out for relief but didn’t fit traditional notions of “fraud on the court.” Lindsey v. Lindsey,9 for instance, involved a wife seeking relief from a divorce decree based on a “severe mental illness” that prevented her from remembering “any event dealing with the dissolution.” Though Lindsey did not include typical facts that support fraud, the Minnesota Supreme Court in Lindsey seemingly broadened the definition of “fraud on the court” to cover equitable circumstances that mirrored some of the grounds in Rule 60.02.10

Not long after, Tomscak v. Tomscak11 outlined even more circumstances in which parties would be allowed to “set aside” stipulated divorce decrees on the grounds of “fraud, duress or mistake.”

And so it went. While the inherent authority to reopen a divorce was presumably limited in nature, courts struggled to address the variety of “peculiar facts” that seemed to justify reopening.12 And as more peculiar facts arose, this once-limited power expanded into a far more robust form of equitable relief available to right all manner of wrongs. With each new exception, case law created more and more ways a divorce could unravel, even years after it was supposed to be over.

Chapter 2: Finality ascendant.

In search of a more definitive standard, the Minnesota Legislature adopted a new statute grafting a more limited version of the civil standard for post-judgment relief into family actions (with a notable exception).13 This 1988 statute, Section 518.145, subdivision 2, thus provided parties with a mechanism to reopen divorce decrees or other family court orders for one of five enumerated reasons:

(1) mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect;

(2) newly discovered evidence which by due diligence could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial under the Rules of Civil Procedure, rule 59.03;

(3) fraud, whether denominated intrinsic or extrinsic, misrepresentation, or other misconduct of an adverse party;

(4) the judgment and decree or order is void; or

(5) the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged, or a prior judgment and decree or order upon which it is based has been reversed or otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judgment and decree or order should have prospective application.14

At the outset, section 518.145 appeared to provide most of the relief that was available under the Rules of Civil Procedure (with the exception of the general “any other circumstances” bases). And not long after the statute’s enactment, Minnesota courts began directing parties away from equitable arguments, and directing them to section 518.145.15

Eventually, the Minnesota Supreme Court held that the days of ever-expanding equitable relief were gone and that finality governed. Shirk v. Shirk16 thus involved an ex-wife seeking to amend her divorce decree due to improper behavior by her divorce attorney, who was investigated by the professional board. Just as courts had done in the years prior to section 518.145, the district court and court of appeals vacated the decree based on the “serious violation of trust” and “incompetence of counsel.”17 Yet the Shirk Court reversed, finding that the section 518.145, subdivision 2 excluded all relief “not among the listed grounds.”18 In this way, Shirk represented a shift away from the equitable principles that sought to provide parties relief and instead prioritized the finality of the divorce decree.

Over the following decades, courts held the line, defending section 518.145’s relief as narrowly tailored and limiting. Courts thus distinguished section 518.145’s relief from the “open-ended power” granted to Rule 60.02.19 Thus even seemingly broad relief, such as inequitable prospective application, couldn’t be used as a “catchall provision” but had to be applied with “due caution.”20 Following Shirk, spouses could no longer seek relief for incompetent counsel, their own lack of capacity, or unanticipated consequences of their decree.21

Finality, it seemed, was the order of the day. And divorced spouses could rest assured that their decree would remain final, subject only to the limited, enumerated grounds set by the Legislature rather than the vast bounds of equity.

Chapter 3: Equity strikes back.

Such was the state of the laws for nearly two decades, until equity’s pull began to assert itself once more.

In 2022, the Minnesota Supreme Court chipped away at Shirk’s limited view in Bender v. Bernhard and Pooley v. Pooley, paving two additional pathways to reopening—post-decree evidence and omitted assets.

Favoring the equitable considerations at play, Bender undercut the principle of finality by redefining Section 518.145’s “newly discovered evidence” ground for relief to include post-decree evidence.22 Before Bender, a party seeking to reopen a divorce decree based on newly discovered evidence could only do so if the evidence existed at the time of the decree. This historical approach preserved finality by barring a reopening due to new or changing circumstances.

Challenging this principle, the mother in Bender moved the district court to extend her ex-husband’s child support payments based on a Social Security Administration report that post-dated the child support order.23 After the district court refused to consider the evidence, a 4-3 majority in Bender reversed, and directed the lower court to reopen the child-support order to consider the new evidence, dispensing with the “bright-line rule” safeguarding finality and instead valuing equitable considerations most of all.24 After Bender, new evidence (not just newly discovered evidence) may upend a decree without concern for finality. By contrast, three members of the Court argued that finality should remain supreme. Per the dissent, to hold otherwise would undermine the purpose of Section 518.145, subd. 2 and judicial certainty.

Six months later, the Court—dividing along the same 4-3 lines—returned to a similar issue in Pooley v. Pooley,25 further weakening finality by allowing allocation of any assets not addressed in a prior divorce decree.26 In keeping with Shirk’s holding, the district court denied the wife’s request to divide husband’s previously omitted retirement account.27 Once again, the Supreme Court reversed, this time holding that despite the six years since the divorce, wife could still seek to divide these assets as “omitted” from the original decree, and thus outside the scope of 518.145 limits.28 In choosing equity over finality, the Pooley Court coined an analogy that explained how one could carve out an equitable result from the principles of finality of section 518.145:

. . . . If a court’s decree is a box that contains everything the parties agreed to and what the court has approved as equitable, that box can only be reopened if the factors of section 518.145 are met. But it is not reopening the box to address items that were never inside the box. Multiple items in this case, including waivers of spousal maintenance, are inside the box and cannot be altered unless a party satisfies the requirements of section 518.145. But the retirement assets were never inside the box, as the dissolution court never approved any division as equitable, and it is therefore not reopening the decree to equitably divide those assets….29

Persuaded again by equity, the Court remanded for division of the Pooleys’ omitted assets.30

Leading the dissent, Justice Hudson asserted that the majority “effectively overruled [the Court’s] holding in Shirk and destabilized the finality and reliability of dissolution judgments.”31 In divorce, the dissent emphasized, “the need for finality takes on central importance.”32

The message from the Bender-Pooley Court was clear. Going forward, equity would stand (at least) on par with finality, and courts must vigorously exercise their equitable oversight in divorce matters, even at the risk of uncertainty. In so doing, the Bender-Pooley duo harkened back more than 30 years to the more expansive use of inherent power available to right a broad range of unfairness and misconduct.

Epilogue: What’s a lawyer to do?

While the pivot back to equity will be a welcome relief for some, the fears of opening Pandora’s box aren’t unwarranted.

As earlier case law illustrates, equity may solve some problems, but it invites others—especially for practitioners. And by ringing in a return to equity, Bender and Pooley may raise at least as many questions as they answered. Those unanswered questions will likely first be addressed by practitioners, and the district courts, as matters of first impression.

In getting to these answers, practitioners will first address them as drafting issues. And they might begin by retuning an old tool in the box. Even prior to Pooley, practitioners would occasionally include a clause to account for items unlisted in the decree.33 These “omitted asset” clauses should be revisited in light of Pooley. In reviewing prior drafts of “omitted asset” clauses, practitioners should consider whether including an “omitted assets” clause puts those assets “in the box” for approval by the district court, and thus, applies the timing requirements of section 518.145.

At the same time, practitioners should be careful when choosing how omitted assets are divided. It’s reasonable to conclude that a court could approve an “omitted assets” clause that divides those assets “equitably” or “equally.” In choosing between those words, practitioners remember that equitable does not necessarily mean equal.34 By contrast, it’s less likely that a court could approve as equitable an “omitted assets” clause that divides those assets “to each party in their own name,” or “to each party who possesses the property.”

The drafting issues don’t end there. Practitioners will be left to confront what it means for an asset to be “inside the box” under Pooley. While Pooley provided a framework, Pooley did not decide the various permutations in how practitioners address assets in decrees.35 Parties have offered divorce decrees that exclude the value of their marital assets to protect their privacy. Or parties simply state that personal property and furnishings have been divided equitably between the parties. Is listing the property, but not the value, enough to keep an asset “inside the box”? In confronting these problems, practitioners can revisit (or discover) ways to provide to the district court the necessary information to approve a stipulation as equitable, while preserving the parties’ desire for privacy.36

Pooley and Bender won’t just be a challenge for drafting. Those cases will continue to impact how practitioners litigate post-decree issues. For instance, when does finality even begin? Already the appellate courts struggle to delineate between a final decree and post-decree motions, like a motion for amended findings.37 In a similar vein, practitioners and courts will need to consider when a modification motion is finally decided. Minnesota statute provides that modification of child support and maintenance is retroactive only to the date of service of the motion.38 Bender’s equitable approach to newly discovered evidence may yet extend the reach of that retroactive motion, leaving obligors uncertain as to the finality of their obligations.39

Ultimately, the shift from finality to equity might be a matter of trial and error (and breaking old habits). But even as old habits die hard, practitioners will begin reassessing to prepare for what may hopefully be the final chapter in this journey.

M BOULETTE is an attorney at Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP. They litigate high-stakes divorce and child custody cases, regularly handling multi-million-dollar divorces involving closely held businesses, commercial real estate valuation, fraud and concealed assets, executive benefits, trusts, and inherited wealth, in addition to high-conflict custody cases with allegations of abuse, alienation, or mental health complications.

SEUNGWON CHUNG is an associate in Taft’s domestic relations group. He was part of a team of Minneapolis attorneys recognized as 2022 Attorneys of the Year by Minnesota Lawyer.

ABBY SUNBERG is a Taft litigation associate with experience in commercial litigation, domestic relations, and wealth transfer litigation. She was part of a team of Minneapolis attorneys recognized as 2022 Attorneys of the Year by Minnesota Lawyer.

Notes

1 Bender v. Bernhard, 971 N.W.2d 257, 259 (Minn. 2022).

2 Pooley v. Pooley, 979 N.W.2d 867, 870 (Minn. 2022).

3 See Minn. Stat. §518.18 (modification of custody); Minn. Stat. §518.175, subd. 5 (modification of parenting time); Minn. Stat. §518A.39, subd. 2 (modification of support and maintenance).

4 See e.g. Loo v. Loo, 520 N.W.2d 740, 743–44 (Minn. 1994) (“[T]he principles of res judicata apply to dissolution proceedings subject to the limitation that either party may petition for modification of maintenance….”); Kiesow v. Kiesow, 270 Minn. 374, 383, 133 N.W.2d 652, 659 (1965) (noting that “the doctrine of res judicata is not applied with the same degree of finality in a matter involving the amendment of a divorce decree as in some other actions”);

5 See Minn. R. Civ. P. 60.02 (applying the rule to “a final judgment (other than a marriage dissolution decree”)); Bredemann v. Bredemann, 253 Minn. 21, 24, 91 N.W.2d 84,87 (1958).

6 Bredemann, 253 Minn. at 24, 91 N.W.2d at 87; Lindsey v. Lindsey, 388 N.W.2d 713, 716

(Minn. 1986).

7 The six enumerated grounds under Rule 60.02 are:

(a) Mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect;

(b) Newly discovered evidence which by due diligence could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial pursuant to Rule 59.03;

(c) Fraud (whether heretofore denominated intrinsic or extrinsic), misrepresentation, or other misconduct of an adverse party;

(d) The judgment is void;

(e) The judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged or a prior judgment upon which it is based has been reversed or otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judgment should have prospective application; or

(f) Any other reason justifying relief from the operation of the judgment.

Minn. R. Civ. P. 60.02.

8 Bredemann, 253 Minn. at 25, 91 N.W.2d at 87.

9 388 N.W.2d at 715–16.

10 Id. at 716 (“We must point out, however, that a finding of fraud upon the court and the administration of justice must be made under the peculiar facts of each case.”).

11 352 N.W.2d 464, 466 (Minn. Ct. App. 1984).

12 Lindsey, 388 N.W.2d at 716.

13 Maranda v. Maranda, 449 N.W.2d 158, 164 n.1 (Minn. 1989); 1988 Minn. Laws. 1007, 1011.

14 Minn. Stat. §518.145, subd. 2.

15 See Maranda, 449 N.W.2d at 164.

16 561 N.W.2d 519, 522 (Minn. 1997).

17 Id. at 521.

18 Id. at 522.

19 Harding v. Harding, 620 N.W.2d 920, 923 (Minn. Ct. App. 2001).

20 Id.

21 Anton v. Sparks, A16-0518, 2016 WL 7337097, at *6–7 (Minn. Ct. App. 12/19/2016); Hestekin v. Hestekin, 587 N.W.2d 308, 310 (Minn. Ct. App. 1998).

22 Supra note 1.

23 Id. at 260.

24 Id. at 266.

25 The Court split along identical lines in both Pooley and Bender, with Justices Chutich, Thissen, and Moore joining Justice McKeig’s majority opinion and Justices Hudson, Gildea, and Anderson dissenting.

26 Supra note 2.

27 Id. at 872, 76–77 (citing Shirk v. Shirk, 561 N.W.2d 519, 522 (Minn. 1997)).

28 Id. at 877.

29 Id. at 877 (footnote omitted).

30 Id. at 879.

31 Id. at 884.

32 Id. at 881 (citing Shirk, 561 N.W.2d at 522) (internal quotation omitted).

33 For example, a clause might state: “In the event there are any marital assets that are omitted from this Decree, those assets shall be divided equally between the parties.”

34 See Olness v. Olness, 364 N.W.2d 912, 915 (Minn. Ct. App. 1985).

35 979 N.W.2d at 877.

36 See Minn. Gen. R. Prac. 308.03; Minn. R. of Pub. Access to Records of Jud. Branch 4.

37 Wiel v. Wahlgren, No. A22-0359, 2023 WL 353891, at *5 n.8 (Minn. Ct. App. 1/23/2023); Blessing v. Blessing, No. A21-1709, 2023 WL 1093864, at *8 n.4 (Minn. Ct. App. 1/30/2023).

38 Minn. Stat. §518A.39, subd. 2(f).

39 Snyder v. Snyder, 212 N.W.2d 8669, 875 (Minn. 1973) (commenting that finality is important to allow spouses “to make reasonable plans for the future based on the economic obligations imposed upon [them] by the decree of divorce”).