By Amy Lindgren

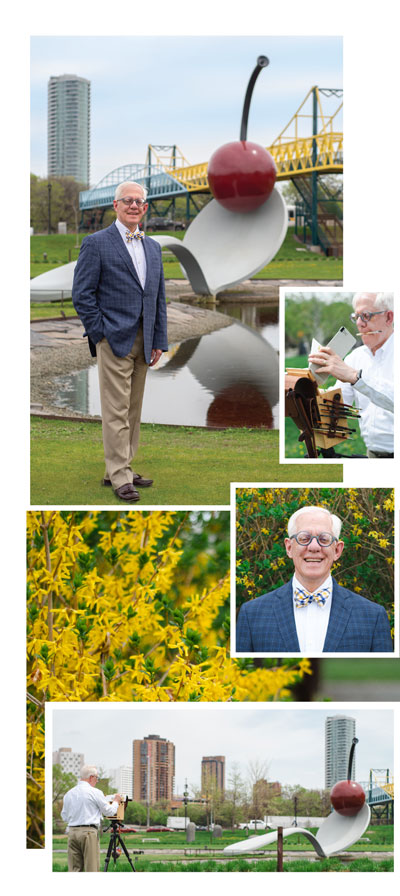

If you ask Paul Floyd how he sees himself, the response won’t be glib or simple. He’s been thinking about this for a while; as the incoming president of the Minnesota State Bar Association, he knows he’ll be introducing himself to 13,000 members statewide, becoming the public face of the organization that both serves attorneys and gives them a voice. Eventually Floyd does settle on an answer: He sees himself as a person who builds bridges, creating a conduit for communication and a pathway for people with divergent viewpoints to connect and find previously unrecognized common ground.

“Building bridges,” he says, “is a theme that runs throughout my childhood, my adulthood, my role as a senior attorney, and now in my role as the bar president.” Those are the broad strokes covering his 67 years; the specifics include 40 years of law practice, a seminary degree, 25 years of volunteering for a Ukrainian-based nonprofit, leadership of two bar associations (MSBA makes three), and more than two decades as an adjunct professor for two universities—all built upon a foundation of barely speaking or reading in the first years of his life and growing up with the expectation of being a housepainter.

Hard times

According to Floyd’s twin sister, Leslie Floyd, she, Paul, and their older brother, David, grew up impoverished—a fact Paul didn’t seem to register until his mother completed their financial forms for college grants. “That’s when I realized we were poor,” she recalls Paul saying. But Leslie, a historian by profession, remembers in scholarly detail the turn-of-the-century farmhouse the family rented in Lima, Ohio after moving from nearby Cuyahoga Falls when their parents divorced. The weathered home had bats in the attic and no upstairs heat, despite winter temperatures that regularly dipped below freezing. Paul and David shared one of the two bedrooms, while Leslie and their mother shared the other. The family of four had no car, which meant a four-mile walk for the kids to hang out at the mall and a somewhat embarrassing weekly ride to church in the funeral home director’s black limousine. “My mother didn’t feel comfortable at the Baptist church because she was divorced,” Leslie recalls, “but she encouraged us to go. The local funeral home guy would come get us and we used to lie flat in the back so the neighbors wouldn’t see us in the limousine.”

These stories are told with a laugh and the acknowledgement that a lot of people were “of modest means” in their community. Like other kids, the Floyds earned extra money delivering the newspaper, and Paul played with his friends in the back lot of the nearby ball-bearing plant, more than once sustaining injuries that required stitches. The 1960s and ‘70s were a tumultuous time to grow up in Lima, an industrial town that experienced racial discord and violence, accompanied by frequent lockdowns at their high school. Through it all, their mother went to work every day in advertising at the Montgomery Ward store, and the Floyd children walked to school and back. Their parents had divorced when the twins were five, and their dad returned to South Carolina, where he’d been raised. Paul says they didn’t have much contact with him except for one conversation he remembers from his teens when his dad called from jail. The state of Ohio had apparently caught up with their father for not paying child support, resulting in a six-month stint on a chain gang down south.

Despite not interacting with their father, the Floyd children did travel south many summers to see their paternal grandparents, an experience that deeply impressed Paul. Seeing southern towns that were effectively segregated made him think more critically about race issues and kindled his instinct to be a bridge between the perspectives held by the northern and southern sides of his own family. Floyd says. “I’ve always struggled over the north-south dynamic in our family. I don’t have an answer to it, but I’m sensitive to the reality that was inherently there.” If he didn’t consider himself impoverished as a youth, Floyd sees the picture more clearly now. In particular, he remembers being deemed a remedial student in grade school, which might not have happened in a family with more resources. First came the years when he didn’t speak, relying on his sister to do the talking. That began to clear up just when it was time to learn math and reading—two things he couldn’t seem to master. Someone finally realized when he was eight or nine that he couldn’t see the board, but by the time he received his free glasses from the Lions Club, he was hopelessly behind. A case of dyslexia that wasn’t diagnosed until well into his adult years further complicated his education. For lack of resources and guidance, Floyd did poorly in school. Assuming he wasn’t college material, he set his sights instead on a career working with his hands.

A gift from a stranger

As soon as he was old enough, Floyd took a job selling paint and tools at the local Sears store. He spent his junior and senior years of high school running track, earning Cs and Ds in his classes, and riding his sister’s sparkly purple banana-seat bike back and forth to work. (His own bike had been stolen.) He had chosen house-painting as a likely vocation and probably would have stuck to that plan if something fairly amazing hadn’t happened: A stranger offered to pay half of his tuition if he went to college. To be fair, this wasn’t a complete stranger—it was someone with whom Floyd had struck up a correspondence after hearing him speak at a youth rally. Tony Campolo, a left-leaning evangelical speaker who would eventually become one of President Clinton’s spiritual advisors, made Floyd an offer he couldn’t refuse: Attend one of three religious colleges recommended by Campolo, and he would pay half the cost.

For the first time, Floyd says, college seemed real to him. Of the three options, he chose Judson College outside of Chicago, where he majored in political science and history. It was a tiny campus that was only recently accredited at the time he enrolled, but it had an unbeatable policy: Students earning high grades would be comped half of their tuition—which for Floyd could mean no tuition costs at all because of Campolo’s gift. Floyd threw himself into the challenge, not just earning honors but managing to complete his degree in two and a half years.

For the first time, Floyd says, college seemed real to him. Of the three options, he chose Judson College outside of Chicago, where he majored in political science and history. It was a tiny campus that was only recently accredited at the time he enrolled, but it had an unbeatable policy: Students earning high grades would be comped half of their tuition—which for Floyd could mean no tuition costs at all because of Campolo’s gift. Floyd threw himself into the challenge, not just earning honors but managing to complete his degree in two and a half years.

Floyd still needed student jobs to pay for his room and board, which was a stroke of luck on two counts: It was at one of those jobs that his future wife, Donna, first saw him, while another position led to his interest in law. In truth, Donna would probably have seen him anyway in their time at Judson, since there were only 500 students on campus. But Floyd stood out as one of the college janitors, frequently mopping floors or cleaning the halls as she walked past. They hung out with mutual friends, and Paul eventually asked her out to a drive-in movie. That first date is memorable on many counts, Donna says, not least because Paul’s cousin was in the front seat—Paul still didn’t have a driver’s license, much less a car. The three of them arrived at the movie in his aunt’s Mustang, and the cousin turned halfway around in the driver’s seat to keep up a conversation with Paul and his date in the back. The movie was Blazing Saddles, and it wasn’t until much later that Paul told Donna he wasn’t sure if he should laugh at the more bawdy jokes in front of her.

Despite its cringe-inducing potential, the outing went well enough to yield another. Eventually Donna and Paul set a date to marry two days after graduation. In the meantime, Floyd’s other job as a teaching assistant for his political science professor was helping to set his professional course. His professor was also an attorney in private practice and one day he asked Floyd if he’d like to see an appellate court proceeding. Floyd jumped at the chance, traveling with another student into Chicago to see his professor argue a case at the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. On the same trip, the professor took them to another courtroom in Cook County where they were able to observe a civil trial involving police officers who had shot and killed the Black Panther Party activists Fred Hampton and Mark Clark at their Chicago apartment in 1969. Floyd recalls seeing the courtroom reconstruction of the shooting scene, and the strings used to show the trajectory of the bullets. Between his professor’s intellectual arguments in the first case and the drama of the second, Floyd’s mind was made up: “I knew I wanted to be an attorney.”

But first, there was the matter of his writing. Although Floyd was making good grades, his undiagnosed dyslexia continued to plague his paperwork. Without his asking, a Judson teacher took him aside and stated bluntly, “If you don’t learn how to spell and write and articulate well, people will assume you’re ignorant. No one will believe anything you say and you’ll have no credibility.” As Floyd recalls, she spent a semester tutoring him privately, telling him to forget everything he’d tried to learn in high school and start over. “She actually invested in me,” he says. The lessons took and, although Floyd never fully mastered spelling, he improved to the point that law school no longer seemed out of reach. Even so, he put off enrollment to follow one more piece of advice from his political science professor: Try something else before law school so you know better what kind of law you want to practice. Floyd chose seminary as his “something else,” applying at St. Paul’s Bethel Seminary. Shortly afterward, Donna was offered an actuarial position in Minneapolis. The two moved north and began their married and professional lives.

Launching a career

Launching a career

So, if Floyd went to seminary, why isn’t he a pastor instead of a lawyer? First, because he maintained his love for the law even through four years of theological training and a Master of Divinity degree (with honors) in New Testament Studies. And second? They told him not to become one. Apparently the program’s personality and vocational testing suggested that he would be likely to wash out if he went into pastoral ministry. Not one to ignore good advice, Floyd tilted his studies to the theological side and savored the experience of learning for its own sake. He also enjoyed traveling around the country co-teaching seminars on youth ministry and the exposure to different points of view that it gave him. Three months after graduating from Bethel, he arrived at William Mitchell for his first law school classes; three years later he began his career clerking for Justice C. Donald Peterson at the Minnesota Supreme Court and then moved into a litigation practice as an associate at Arthur Chapman & Michaelson.

Kate MacKinnon, who practices from the Law Office of Katherine L. MacKinnon in St. Paul, remembers meeting Floyd when she started as an associate in the same firm a year after he did. “We were both kind of nerdy,” she remembers, “so we hit it off.” They worked on numerous cases together while also representing the firm at law school recruiting events and sharing what MacKinnon calls “a certain level of dog-with-a-boneyness” in searching for arcane case law to support their legal arguments. She remembers Floyd as being simultaneously very funny and very “buttoned down, even for Minnesota.” For his part, Floyd remembers receiving important advice from MacKinnon. Trying to sound more like his own notion of a lawyer, Floyd had begun swearing in their conversations. To which he says MacKinnon replied: “Stop that. That’s not you. First of all, the f-word is not believable when you say it. You don’t even do it convincingly. And second, you don’t need it. You think it makes you sound stronger but it doesn’t.” Floyd says he hung up the phone from that conversation thinking, “She just gave me a gift. Kate was saying, ‘Go with being the nice guy. Instead of trying to sound tough, be patient, and if the other attorney is being unreasonable, you can give people just enough rope to hang themselves.’”

Sidebar: As a rule, clients want their attorneys to be competent, learned, persistent—but artistic? For Paul Floyd, practicing art as a discipline has been a part of his life since around 2009, or about a third of the time he’s been a practicing lawyer. Read more about the artful lawyer

And so he became a nice-guy lawyer, a bridge builder, a person who holds high standards and helps others do the same. It would take a few more years, but the same process of developing his identity as an attorney would also lead him away from litigation to transactional law, and then to his current focus on helping other attorneys navigate issues in their own practices. Eric Cooperstein, a Minneapolis attorney and friend whose practice is devoted to ethics, has seen some of that evolution since meeting him in connection with a case in 2007. “Even in the time I’ve known him," Cooperstein says, “I’ve seen Paul’s views on things evolve. He’s the kind of person who can engage in self-reflection, and he’s very open-minded.” Cooperstein sees Floyd’s practice as a good fit for his many interests, as well as his goal of helping others. “Paul loves the business side of law,” he says. “I don’t know if there are a lot of lawyers who regularly read the Harvard Business Review, but he does and he applies what he reads with the attorneys he counsels.”

If the change in his practice fits Floyd’s evolving vision of himself, so too does his consistent level of volunteer and leadership work. Whether it derives from wanting to pay back the investment others have made in him, or a simple desire to be of service, Floyd has managed to give away thousands of hours of high-level work in his career. His volunteering has ranged from leadership roles in churches where he and Donna have been members to his affiliation since 1997 with Shepherd’s Foundation, a nonprofit serving people in Ukraine, where he has traveled more than a dozen times. Dr. Marshall Wade, the foundation’s board chair, credits Floyd (currently the organization’s president) with a huge impact, particularly on the Ukrainian side of the operations. “Paul is a fantastic consultant in terms of the business side, and certainly the legal ramifications of decisions,” Wade says.

Wade notes that the level of corruption in Ukraine in the early days of Floyd’s involvement was pervasive, making his style of ethical leadership even more impactful as he helped the group adapt from its original mission of providing health services to becoming a camp for disabled children to its current role as an assistance center for war refugees since the Russian invasion. Located about 90 miles south of Kyiv, the foundation considered closing at one point because of problems with government compliance. As Wade relates, “Paul just kept working the problem. He said, ‘I think we can do this,’ and he just kept pushing through, breaking it down until we got through it. Paul was pivotal in just working the problem and not giving up.”

In addition to his work with nonprofits and churches, Floyd has also contributed significant time to multiple bar associations. Besides the MSBA leadership track now culminating in his year as president, he has also served as president of both the Hennepin County Bar Association (2016) and the Minnesota Chapter of the Federal Bar Association (1993-1994). Leny Wallen-Friedman, Floyd’s recently retired law partner, describes Floyd as “dedicated to public service. You can just see that from what he’s done. He has a very good vision and he’s effective at moving organizations forward. A lot of people are willing to help but they’re not skilled at it the way he is.” Wallen-Friedman, who was Floyd’s partner for more than 20 years before retiring, also notes with a laugh that Floyd was never driven to find work when they practiced together. “We always had enough work,” Wallen-Friedman says, “but he was never interested in working extremely hard. He always wanted to have a balance so he could do these other things in his life. To a certain degree he was ahead of his time on that.”

One of those other things in Floyd’s life has been teaching, a pursuit he took up in 2005 as an adjunct professor for Bethel University, where he currently serves as a lead faculty member in the MBA program. In 2018, he began teaching on business subjects at the University of St. Thomas School of Law. In his sessions with students, Floyd acts as an instructor and as a mentor, and also shares from his own life in the hopes of helping others with unseen difficulties. He has been open about his own dyslexia, and that openness is sometimes rewarded when students approach him for advice or support for their own learning disabilities.

Another of those “other things” Floyd has made time for throughout his career has been international travel and bike trips with Donna, as well as more local bike trips with friends such as Dennis Smith, an attorney and long-time mentor who now lives in Colorado. Smith calls his friend “an exceptional cyclist” who makes trips fun. At 67, Floyd is still biking, still practicing law, still volunteering, still providing bar leadership. At an age when many are slowing down, he seems to be picking up speed, adding pursuits such as art to his list of activities (see sidebar, next page).

Another of those “other things” Floyd has made time for throughout his career has been international travel and bike trips with Donna, as well as more local bike trips with friends such as Dennis Smith, an attorney and long-time mentor who now lives in Colorado. Smith calls his friend “an exceptional cyclist” who makes trips fun. At 67, Floyd is still biking, still practicing law, still volunteering, still providing bar leadership. At an age when many are slowing down, he seems to be picking up speed, adding pursuits such as art to his list of activities (see sidebar, next page).

As Floyd enters his MSBA leadership year, he intends to continue building bridges, contributing his skills as a mediator and advocate. “I think what I bring is the ability to listen and to allow people to have a voice and feel like they’re part of the bar association,” he says. “It’s not an initiative or an agenda, because I’ve learned that the process is more important. If the people in the room feel they have made a contribution, the decision will reflect them and they’ll be more likely to support it. I can be a bridge to make that happen, to let the bar association find its own voice.” Cooperstein, who served as HCBA president just ahead of Floyd, says his friend does well in leadership roles because “he’s driven by service, not by ego. He’s not afraid to ask for help or new ideas.” Cooperstein believes Floyd will get that help if he asks, because of the bridges he has taken care to build during his career. “Paul knows a lot of lawyers and he’s stayed in contact with them over the years,” Cooperstein says. “He’ll be bringing that to the table when he’s president.”

Five facts about Paul

1) He graduated 8th in his law school class and served as editor of Law Review despite his undiagnosed dyslexia.

2) He has listened to approximately 100 of The Great Courses on tape, on topics ranging from art and literature to history and game theory.

3) He and Kate MacKinnon, a fellow associate at an early job, once researched so deeply for relevant case law that they ended up giving their firm’s partner something they found from the Queen’s Bench in England—the 19th-century Victorian era of British case law. Of note: This was pre-internet.

4) He was on the cover of Minnesota’s Journal of Law & Politics not once but twice in the 1990s—a rare distinction even if the covers were partly a spoof of his buttoned-down demeanor.

5) In 2000, he put his practice on pause for several months to study psychology and marriage and family therapy before deciding to re-launch a law practice focused on helping attorneys build and manage their own businesses.

Bio bits on Paul Floyd

Family

- Raised in Cuyahoga Falls and Lima, Ohio by a single mother, Patricia Ann Floyd

- Siblings: older brother David and younger sister Leslie (Paul’s twin, born seven minutes later)

Education

- Post-graduate studies in Marriage & Family Therapy, Bethel Theological Seminary (2000-2001)

- Juris Doctorate, cum laude, William Mitchell College of Law (1983)

- Master of Divinity, Bethel Theological Seminary (1980)

- Bachelor of Arts with Honors, Political Science, Judson College (1976)

Legal career

- Shareholder, Wallen-Friedman & Floyd, PA, Minneapolis (2002-present)

- Shareholder, Paul M. Floyd, PA, Minneapolis (2000-2002)

- Partner, Rau & Floyd, PLLP, Minneapolis (1996-2000)

- Partner and associate, Fruth & Anthony, PA, Minneapolis (1987-1996)

- Associate attorney, Arthur Chapman & Michaelson, Minneapolis (1984-1987)

- Judicial law clerk, Justice C. Donald Peterson, Minnesota Supreme Court (1983-1984)

Professional leadership roles & memberships (selected)

- President, Minnesota State Bar Association (2023-2024); Executive Council member (2020-present)

- Chair, MSBA Solo Small Firm Council (2019-2020); council member (2018-2020)

- President, Hennepin County Bar Association (2016-17); Executive Council member (2013-2017)

- Board of Directors, Hennepin County Bar Association (2005-2007; 2012-2018)

- Member, Hennepin County Bar Foundation (2003-2007; 2013-2018)

- President, Hennepin County Bar Foundation (2006-2007)

- Co-Chair, MSBA Challenges to the Practice of Law Task Force (2013-2015)

- Member, Ethics Panel, Hennepin County Bar Association (1992-1998; 2000-2003)

- 8th Circuit vice president, Federal Bar Association (1996-1999)

- President, Minnesota Chapter of the Federal Bar Association (1993-1994)

Additional work experiences

- Adjunct professor, St. Thomas University School of Law (2018-present)

- Adjunct professor, Bethel University College of Adult & Professional Studies (2018-present)

- Adjunct professor, Bethel University MBA program (2005-present) (lead faculty)

- Adjunct professor, Bethel University College of Arts & Sciences (2005-2009; 2016-2023)

Certifications & bar admissions

- Minnesota

- Federal Circuit Court of Appeals

- United States District Court, District of Minnesota

- 8th Circuit Court of Appeals

- United States Supreme Court

Honors

- Minnesota Super Lawyer, 10+ years

- AV rating by Martindale-Hubble, since 1997

- American Jurisprudence Awards in law school (1st in class) for civil procedure, contracts, professional responsibility, and wills/trusts

Civic volunteering

- Shepherd’s Foundation, Ukraine (1995-present) team member, board member, current president of the Board of Directors

- Call for Justice, LLC, Minneapolis, board member (2010-2016); chair (2015-2016)

- Judson University, Elgin, Illinois, trustee (2015-2018)