By Austen Zuege

By Austen Zuege

Intellectual property (IP) protection for product configurations of comestibles, confections, foodstuffs, and the like have been a matter of dispute in courts for well over a century. A variety of distinct IP rights may be invoked in this context, among them design patents and trade dress (either as a registered or unregistered trademark). Courts have grappled with the limits of such IP rights, seeking to prevent end-runs around the expiration of patent and copyright rights that the Constitution restricts to only limited times.1 Such limits on IP rights embody long-standing Anglo-American legal principles in place since the Statute of Monopolies curbed the English Crown’s practice of granting “odious” monopolies over common commodities to raise funds or bestow favor.2 Cases up to the present highlight continued aggressive assertions of trade dress rights by foodstuff manufacturers—coupled with pushback by courts to deny trade dress rights in purely functional product configurations.

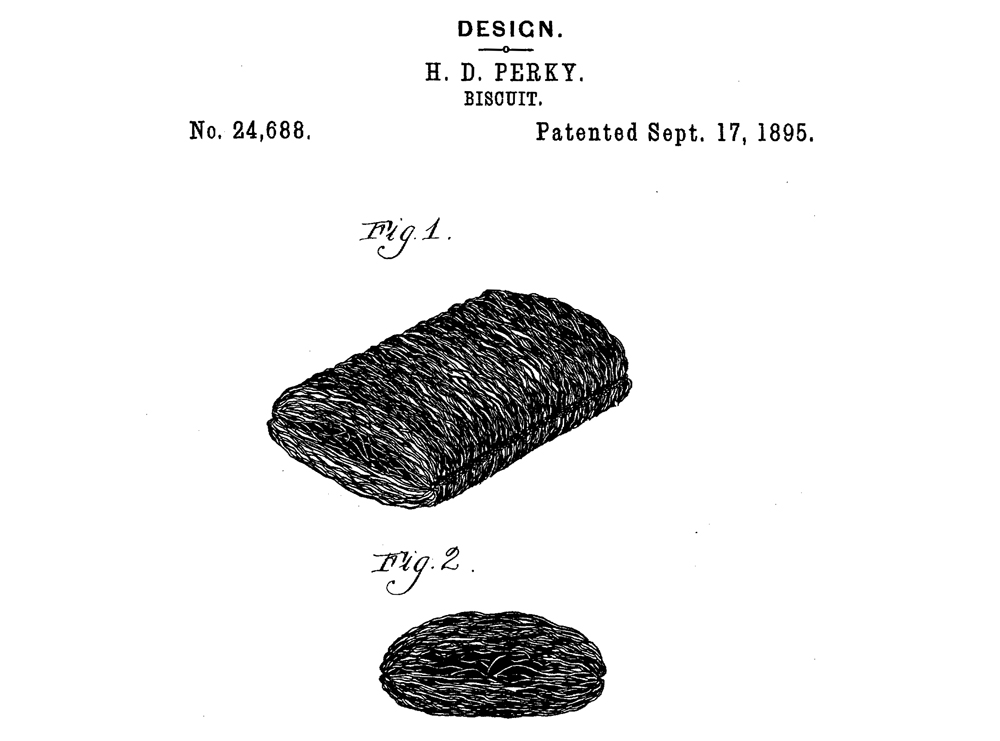

A number of important historical decisions observed the tendency for assertions of trade dress in (food) product configurations/shapes/forms/designs—these terms being used somewhat interchangeably—to inappropriately extend monopoly protections after a patent expired. Judge Learned Hand authored Shredded Wheat Co. v. Humphrey Cornell Co., which dealt with alleged trade dress infringement of the shape of shredded wheat biscuits after the expiration of a design patent to the same biscuit shape.3 He wrote that “the plaintiff’s formal dedication of the design [upon expiration of U.S. Des. Pat. No. 24,688] is conclusive reason against any injunction based upon the exclusive right to that form, however necessary the plaintiff may find it for its protection.”4

Later, the Supreme Court weighed in on a dispute between Kellogg and Nabisco, finding the pillow shape of a shredded wheat biscuit to be functional because “the cost of the biscuit would be increased and its high quality lessened if some other form were substituted for the pillow-shape.”

5 The Court stated,

“The plaintiff has not the exclusive right to sell shredded wheat in the form of a pillow-shaped biscuit — the form in which the article became known to the public. That is the form in which shredded wheat was made under the basic [utility] patent. The patented machines used were designed to produce only the pillow-shaped biscuits. And a design patent [U.S. Des. Pat. No. 24,688] was taken out to cover the pillow-shaped form. Hence, upon expiration of the patents the form... was dedicated to the public.”6

Kellogg has remained the touchstone for cases on the limits of trade dress protection, and not just for foodstuffs. Subsequent decisions have elaborated on the non-functionality doctrine without changing the basic framework.7

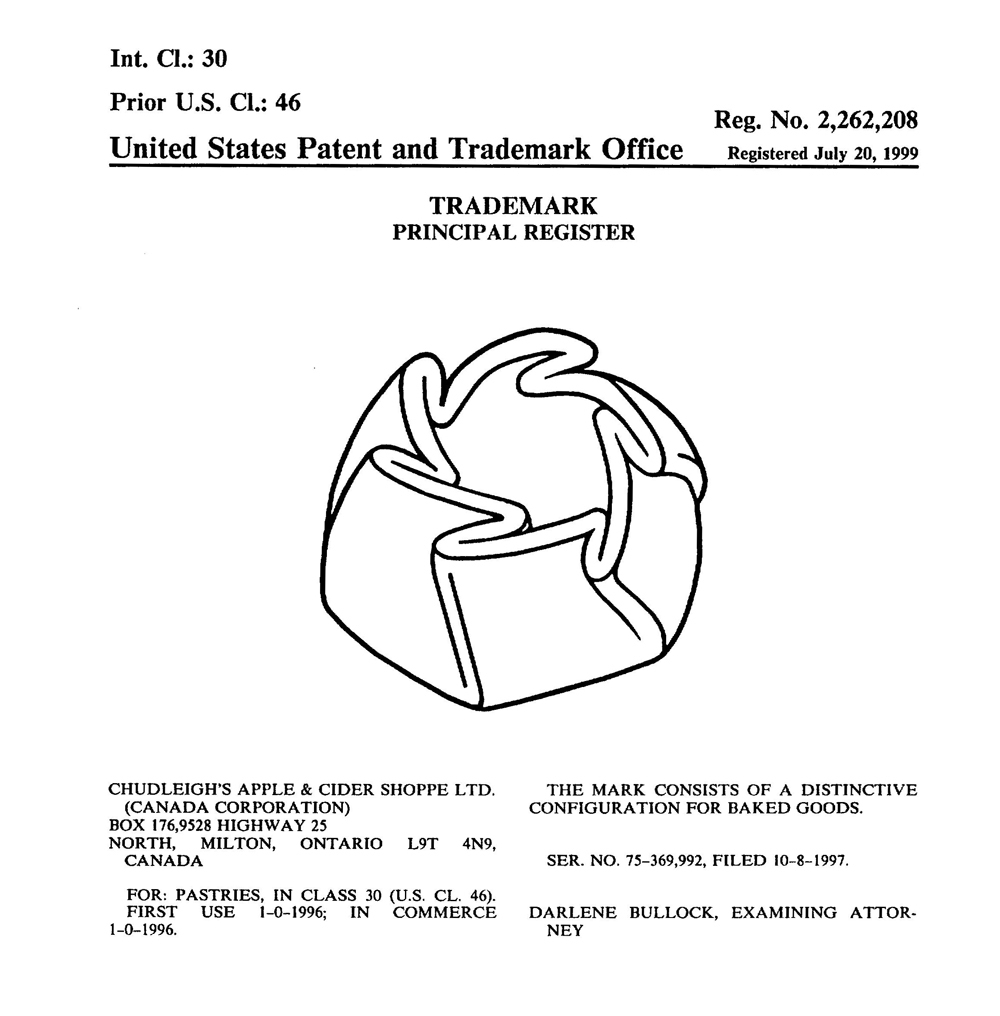

In a more modern case, Sweet Street Desserts, a “Blossom Design” for a round, single-serving, fruit-filled pastry with six folds or petals of upturned dough was held to be functional and, accordingly, unprotectable as trade dress because the product’s size, shape, and six folds or petals of upturned dough were all essential to the product’s ability to function as a single-serving, fruit-filled dessert pastry.8 Only incidental, arbitrary, or ornamental product features that identify the product’s source are protectable as trade dress. Chudleigh’s trade dress Reg. No. 2,262,208 was cancelled.9

In

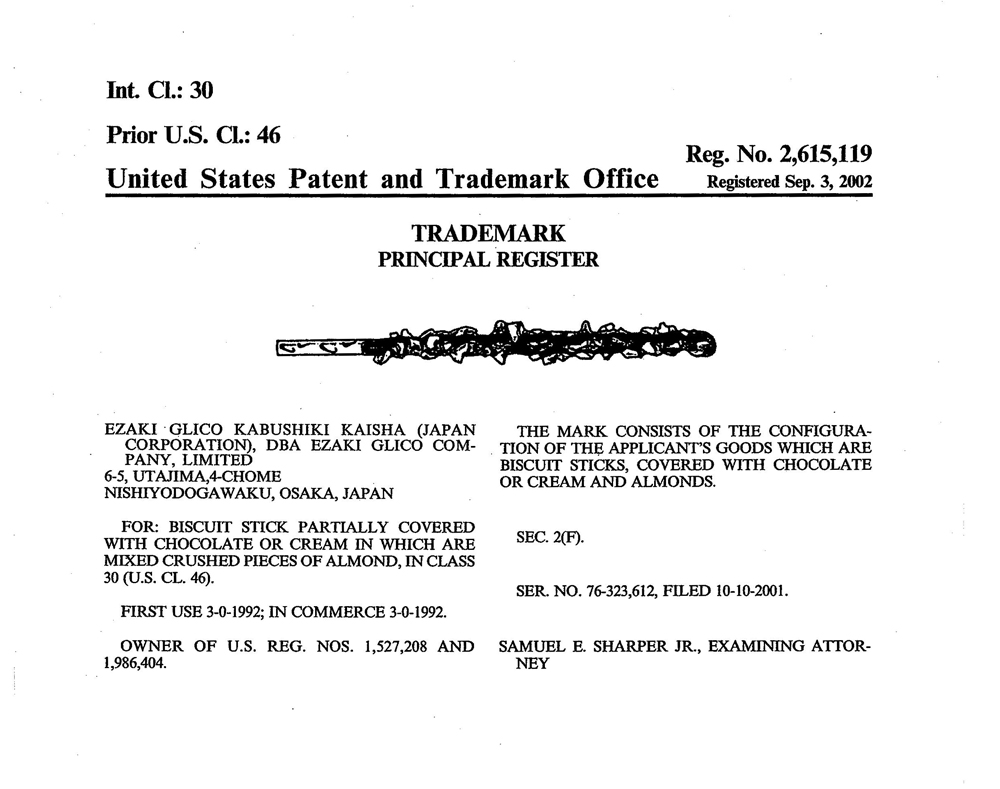

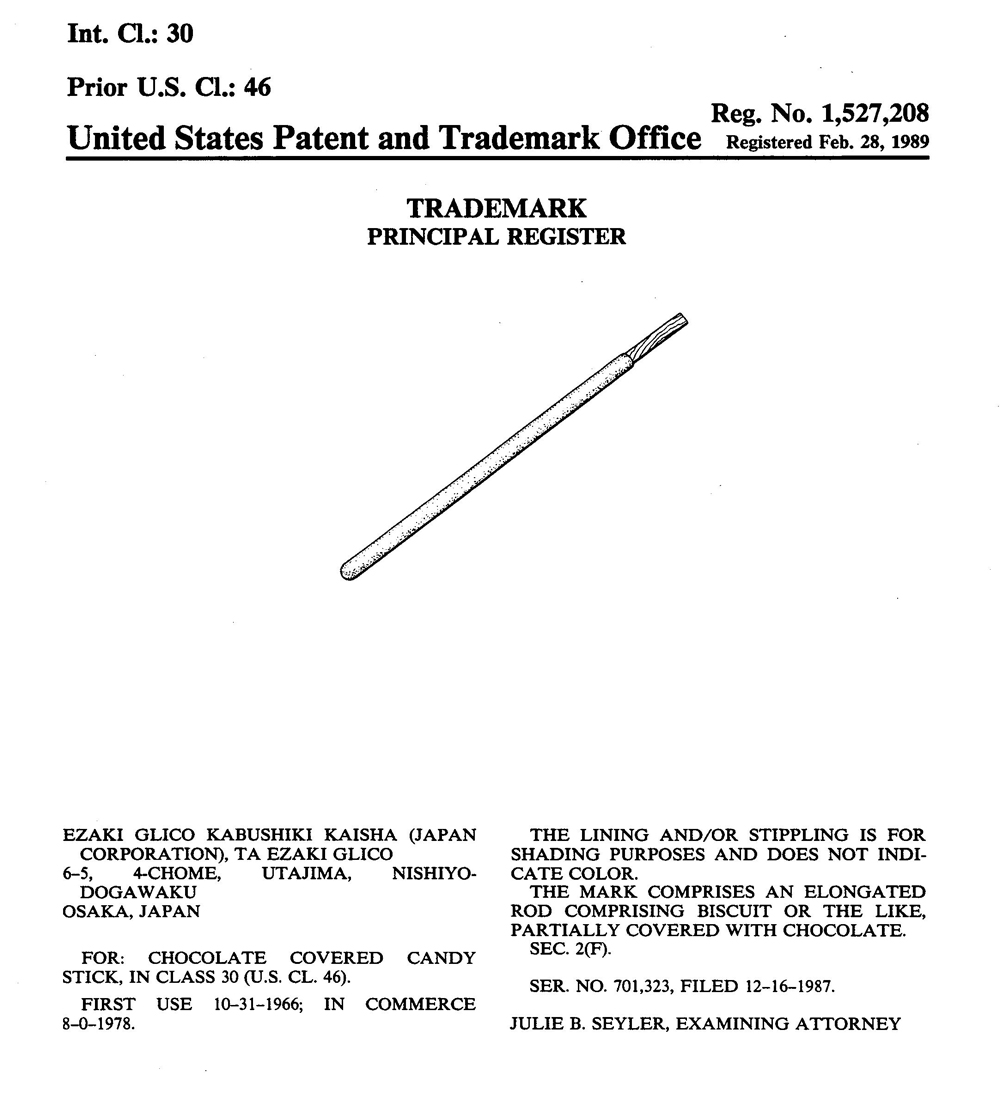

Ezaki Glico v. Lotte, the non-functionality requirement was assessed in connection with Ezaki Glico’s POCKY® treats—thin, rod- or stick-shaped cookies partially coated in chocolate (with optional nuts)—and Lotte’s competing PEPERO® treats.

10

The core dispute was how to define “functional” for product configuration trade dress. Ezaki Glico argued a narrow reading, equating “functional” with “essential.” The court disagreed, reading Supreme Court precedent to say that product configuration features need only be useful to be functional. That is, a product shape feature is “useful” and thus “functional” if the product works better in that shape, including shape features that make a product cheaper or easier to make or use. The 3rd Circuit held that a product feature being “essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article”11 is merely one way to establish functionality.12 A product feature is also unprotectably functional if exclusivity would put competitors at a significant, non-reputation-related disadvantage.13 The rejection of a narrow reading of the functionality doctrine echoes cases in other circuits characterizing the Supreme Court’s TrafFix case as setting forth two ways to establish functionality.14 There are several ways to establish functionality that are not limited to merely “essential” product features.

Functionality in the trade dress context is commonly assessed through the following types of non-dispositive evidence, as summarized in Ezaki Glico:

“First, evidence can directly show that a feature or design makes a product work better.... Second, it is ‘strong evidence’ of functionality that a product’s marketer touts a feature’s usefulness. Third, ‘[a] utility patent is strong evidence that the features therein claimed are functional.’ Fourth, if there are only a few ways to design a product, the design is functional. But the converse is not necessarily true: the existence of other workable designs is relevant evidence but not independently enough to make a design non-functional.”15

There was evidence of practical functions of holding, eating, sharing, or packing the POCKY treats. Ezaki Glico’s internal documents showed a desire to have a portion of the stick uncoated by chocolate to serve as a handle. The court also noted how the size of the sticks allowed people to eat them without having to open their mouths wide and made it possible to place many sticks in a package. Ads for POCKY treats also emphasized the same useful features. Ezaki Glico proffered nine examples of partially chocolate-coated treats that do not look like POCKY treats, but the court found that evidence insufficient to avoid the conclusion that every aspect of POCKY treats is useful.

Finally, the court concluded that Ezaki Glico’s utility patent U.S. Pat. No. 8,778,428 for a “Stick-Shaped Snack and Method for Producing the Same” was irrelevant. The court’s rationale for that conclusion, however, is rather unconvincing. The utility patent was applied for in 2007, with a 2006 Japanese priority claim, which was long after Ezaki Glico began selling POCKY treats in the U.S. in 1978, and also long before Lotte began selling the accused PEPERO treats in 1983 and the first explicit allegations of misconduct in 1993. That patent was also still in force (i.e., unexpired). The utility patent corresponded to an “ultra thin” version of POCKY treats and Ezaki Glico argued that its patent addressed only one of many embodiments covered by its trade dress.

The lower court discussed utility patent disclosures regarding stick warping formulated like a problem-solution statement16—somewhat akin to obviousness analyses in European patent practice. But unmentioned was how the patent’s disclosed stick holder necessarily produces a partial chocolate coating.17 The 3rd Circuit’s reasoning about the irrelevance of the utility patent is superficial to the point of being mere tautology. The appellate opinion did not address Kellogg’s statement that the form in which a food article was made under an expired “basic” patent was relevant to trade dress eligibility or other circuits’ cases that deemed a prior manufacturing method patent to be relevant. Moreover, the court did not address the way mere descriptiveness of just one good bars registration of a trademark for an entire group of goods encompassing additional, different goods.18 Whether a later-filed patent can ever provide grounds to cancel an earlier trade dress registration for functionality is a question the court essentially avoided deciding.

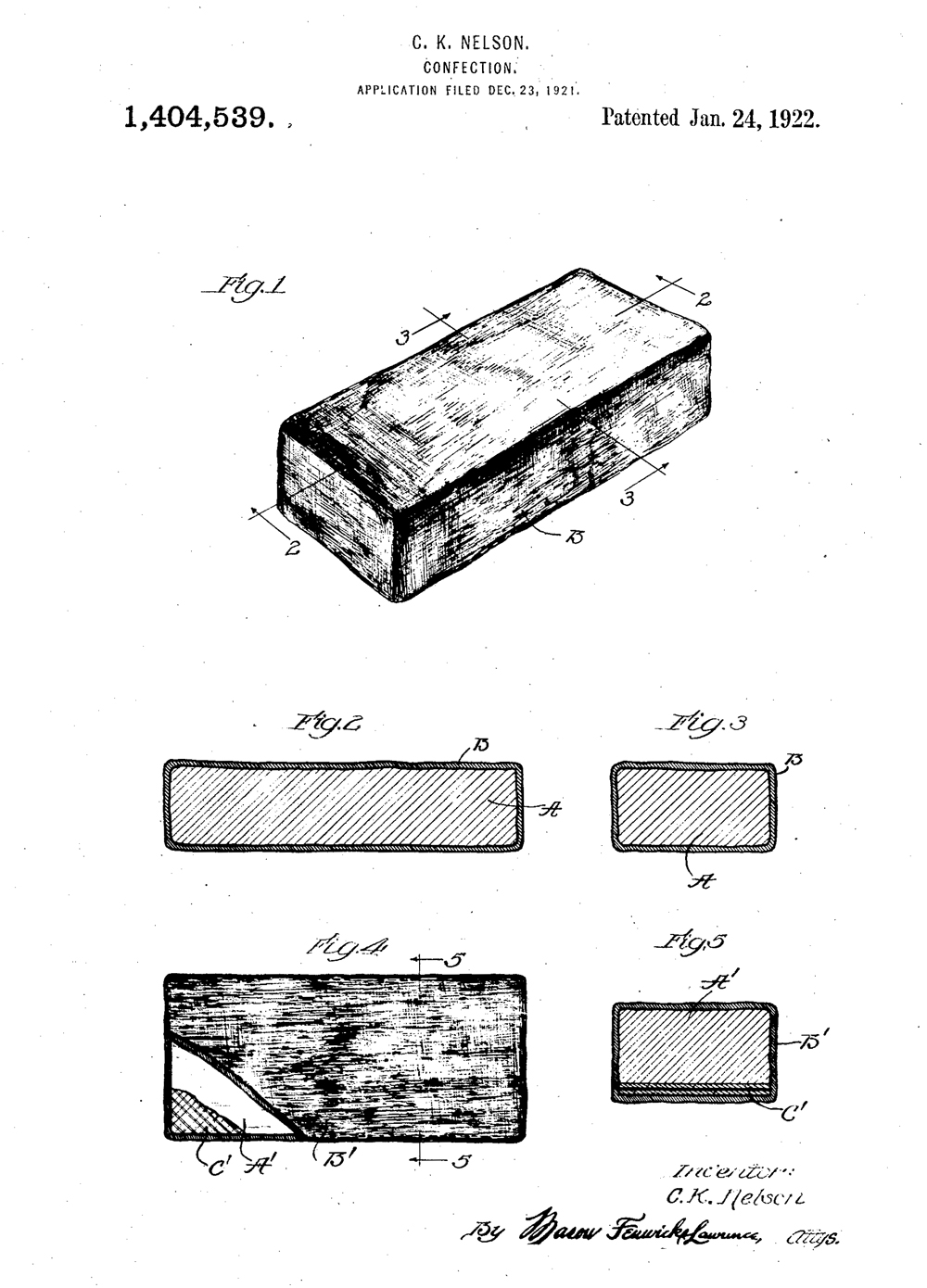

Something else not discussed in Ezaki Glico was the 3rd Circuit’s decision nearly a century ago in the Eskimo Pie case.19 There, the validity of U.S. Pat. No. 1,404,539 on the original ESKIMO PIE chocolate-covered ice cream treat was at issue. The court held the utility patent invalid, reasoning with regard to claim 6 (in which the core and casing form a “substantially rectangular solid adapted to maintain its original form during handling”) that “[t]here is no invention in merely changing the shape or form of an article without changing its function except in a design patent.”20 The rectangular solid shape was found non-functional and therefore unable to distinguish the prior art in a utility patent claim. The lower court had already pithily reached these same conclusions:

“The gist of the invention, if there be one, is in sealing a block of ice cream in a sustaining and self-retaining casing of chocolate. A rectangular piece of ice cream is coated with chocolate…. All that the patentee does is to take a small brick of ice cream and coat it with chocolate, just as candies are coated. [In the prior art,] Val Miller took a round ball of ice cream and coated it, just as candies are coated. In one case the ice cream is round in form, and in the other case it is rectangular. In both cases there is a sustaining and self-retaining casing, sealing the core of ice cream…. There is no invention in form alone.”21

In a fascinating

Wired article from 2015, Charles Duan located correspondence with the inventor’s patent attorney and other pertinent historical information in museum archives.

22 Duan highlighted how the invention, if anything, was really about the particular formulation of chocolate that allowed it to work effectively as a coating on a frozen ice cream treat, while the patent contains no disclosure in that regard and its claims were intended to be preemptive.

23 Invalidation of the ESKIMO PIE patent opened the door for the KLONDIKE® ice cream treat, introduced in 1928, which was later the subject of an 11th Circuit trade dress case about product packaging (as opposed to product configuration) for a wrapper with a pebbled texture, images of a polar bear and sunburst, bright coloring, and square size that, in combination, were held non-functional.

24

Courts have tended to be more lenient on (food) packaging trade dress when it comes to functionality.25 This held true when the 11th Circuit later found the unregistered product design of DIPPIN’ DOTS® multi-colored flash-frozen ice cream spheres/beads to be functional and thus ineligible for trade dress protection.26 An unexpired utility patent (U.S. Pat. No. 5,126,156)—later held invalid and unenforceable27—was specifically cited as evidence of functionality of the product design, along with judicial notice that certain colors connote ice cream flavor.28

So, in 1929, the 3rd Circuit ruled that the configuration of an ESKIMO PIE treat was ornamental and non-functional, and therefore unpatentable in a utility patent; whereas, in 2021, the 3rd Circuit ruled that the configuration of a POCKY treat was functional, and therefore ineligible for trade dress protection. How can these decisions be reconciled?

The only way to square these cases is to say that “functionality” in the trade dress context means something legally different than in the patent context. So, an ice cream treat’s shape/configuration was insufficiently functional to support a utility patent claim though a cookie treat’s shape and configuration was too functional (useful) to support trade dress protection. But courts and other commentators often stop well short of explaining why “functionality” differs in these two contexts, or what specific evidence would differ—aside from the separate need to prove inherent or acquired distinctiveness to establish trade dress rights.29

The ultimate conclusions in the two cases, however, are very consistent in seeking to limit overreaching IP assertions. The functionality doctrine for trade dress has long been used to scrutinize attempts to secure a potentially perpetual trademark monopoly on product feature(s) that consumers desire apart from any unique but optional source-identifying function(s) of product configuration—as well as manufacturer’s concerns about ease and cost of manufacturability.

But the courts have yet to make explicit the precise role, if any, of the relevant consumer’s perspective in this analysis, which would seem to be a legitimate inquiry in the trade dress context in a way it would not be in the utility patent context, for instance. Admittedly, the “ordinary observer” test used for infringement of design patents blurs this distinction somewhat, especially given that one appeals court has held that conflation of the trademark likelihood-of-confusion test and the design patent ordinary-observer test is harmless error.30 But evidence of non-reputational consumer desires, such as a consumer survey or similar expert testimony, would appear to be rather unique to product configuration trade dress considerations and in closer cases might not always be answered or rendered unnecessary by the admissions or conduct of the alleged trade dress owner.

Certainly, many trade dress product configuration cases do turn on admissions or statements (such as ads) by the owner that indicate functionality or the failure of the owner to meaningfully rebut the persuasive articulation of functionality readily observable in the product itself. Additionally, parties aggressively enforcing trade dress have often also pursued or obtained another form of protection, such as a patent, and statements made in or while obtaining a patent on the same or similar subject matter can be relevant to trade dress functionality.31 The Supreme Court has gone so far as to explicitly note that invoking trademark rights as patent rights expire is suspicious enough to create “a strong implication” the party is seeking to improperly extend a patent monopoly and that summary disposition of anticompetitive strike suits is desirable.32 This means consumer surveys or the like should not become routinely necessary. Yet cases may arise where consumer perceptions of functionality (or usefulness) are not immediately apparent from the product configuration itself, or the plaintiff has not made damaging statements, making survey evidence informative in the absence of more straightforward grounds for assessing functionality. This seems like a potential additional (fifth) category of functionality evidence not spelled out in cases like Ezaki Glico.

Foodstuff product configuration trade dress disputes provide an excellent case study of how courts have sought to preserve consumer access to functional product features, as well as producer access to easy and economical manufacturing techniques. Unless product configurations are relatively easily avoided by competitors making basically the same products, assertions of trade dress protection in pure product configurations have often been rejected. While courts remain sensitive to potential confusion over a product’s source, valid product configuration trade dress rights, as a matter of branding, should include a prominent, non-functional feature related to reputation that does not significantly diminish consumer enjoyment or ease of manufacturability.

AUSTEN ZUEGE is an intellectual property attorney & officer with Westman, Champlin & Koehler, P.A. in Minneapolis. Views expressed are the author’s own.

Notes

1 U.S. Const., Art. I, §8, cl. 8

2 See Graham v. John Deere Co. of Kansas City, 383 U.S. 1, 5-6 (1966); Darcy v. Allein, 11 Co. Rep. 84, 77 Eng. Rep. 1260 (K. B. 1603).

3 Shredded Wheat Co. v. Humphrey Cornell Co., 250 F. 960 (2d Cir. 1918).

4 Id. at 964.

5 Kellogg Co. v. National Biscuit Co., 305 U.S. 111, 122 (1938); see also Graeme B. Dinwoodie, “The Story of Kellogg Co. v. National Biscuit Co.: Breakfast with Brandeis,” Intellectual Property Stories (Dreyfuss and Ginsburg, eds., Foundation Press, 2005) available at https://works.bepress.com/graeme_dinwoodie/28 .

6 Kellogg, 305 U.S. at 120-21; see also “Henry Perky: Patents,” Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Perky#Patents (last visited 1/7/2021); U.S. Des. Pat. No. 48,001.

7 See TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 28-32 (2001); Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Brothers, Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 213-16 (2000); Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 164-65 (1995); Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763, 771,775 (1992); Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc., 489 U.S. 141 (1989); Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 850 n.10 (1982); Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. Stiffel Co., 376 U.S. 225, 228-32 (1964); Compco Corp. v. Day-Brite Lighting, Inc., 376 U.S. 234, 238 (1964); see also Scott Paper Co. v. Marcalus Mfg. Co., Inc., 326 U.S. 249, 255-57 (1945).

8 Sweet Street Desserts, Inc. v. Chudleigh’s Ltd., 69 F. Supp. 3d 530, 532-33 and 546-50 (E.D. Pa. 2014) aff’d 655 F. App’x 103 (3d Cir. 2016); see also 15 U.S.C. § 1064(3).

9 Sweet Street Desserts, Inc. v. Chudleigh’s Ltd., No. 5:12-cv-03363 (E.D. Pa., 1/15/2015) aff’d 655 F. App’x 103.

10 Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte Int’l Am. Corp., 986 F.3d 250 (3d Cir. 2021) cert denied 595 U.S. ___ (11/1/2021).

11 Qualitex, 514 U.S., at 165 (quoting Inwood, 456 U.S. at 850, n.10).

12 Ezaki Glico, 986 F.3d at 257.

13 Id. (quoting TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 32).

14 Dippin’ Dots, Inc. v. Frosty Bites Dist., LLC, 369 F.3d 1197, 1203 (11th Cir. 2004); Groeneveld Transp. Efficiency, Inc. v. Lubecore Int’l, Inc., 730 F.3d 494, 506-09 (6th Cir. 2013); Schutte Bagclosures Inc. v. Kwik Lok Corp., 193 F. Supp. 3d 245, 261-62 (S.D.N.Y. 2016) aff’d 699 F. App’x 93, 94 (2d Cir. 2017).

15 Ezaki Glico, 986 F.3d at 258 (internal citations omitted); but see James J. Aquilina, “Non-Functional Requirement for Trade Dress: Does Your Circuit Allow Evidence of Alternative Designs?” AIPLA (5/5/2020) available at https://www.quarles.com/content/uploads/2020/05/Non-Functional-Requirement-for-Trade-Dress.pdf .

16 Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte Int’l Am. Corp., No. 2:15-cv-05477, 2019 WL 8405592 at *6 (D.N.J., 7/31/2019).

17 See holder (61). U.S. Pat. No. 8,778,428, FIG. 5 and col. 5, lines 15-18 & 45-50.

18 See TMEP §1209.01(b) (Oct. 2018).

19 Eskimo Pie Corp. v. Levous, 35 F.2d 120 (3d Cir. 1929).

20 Id. at 122; see also, e.g., E.H. Tate Co. v. Jiffy Ents., Inc., 196 F. Supp. 286, 298 (E.D. Pa. 1961); James Heddon’s Sons v. Millsite Steel & Wire Works, 128 F.2d 6, 13 (6th Cir. 1942).

21 Eskimo Pie Corp. v. Levous, 24 F.2d 599, 599-600 (D. N.J. 1928).

22 Charles Duan, “Ice Cream Patent Headache,” Wired (10/20/2015) available at https://slate.com/technology/2015/10/what-the-history-of-eskimo-pies-says-about-software-patents-today.html .

23 Id.; cf., Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 223-24 (2014); Mayo Collab. Servs. v. Prometheus Labs, Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 72-73 (2012).

24 AmBrit, Inc. v. Kraft, Inc., 812 F.2d 1531, 1535-38 (11th Cir. 1986), cert. denied, 481 U.S. 1041 (1987), abrogated by Wal-Mart, 529 U.S. at 216, but see The Islay Co. v. Kraft, Inc., 619 F. Supp. 983, 990-92 (M.D. Fla. 1985).

25 E.g., Spangler Candy Co. v. Tootsie Roll Inds., LLC, 372 F. Supp. 3d 588, 604 (N.D. Ohio 2019); Fiji Water Co., LLC v. Fiji Mineral Water USA, LLC, 741 F. Supp. 2d 1165, 1172-76 (C.D. Cal. 2010).

26 Dippin’ Dots, 369 F.3d at 1202-07; see also 15 U.S.C. §1125(a)(3). The court incorrectly stated unregistered product configuration trade dress can be inherently distinctive, a position abrogated by Wal-Mart.

27 Dippin’ Dots, Inc. v. Mosey., 476 F.3d 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

28 Dippin’ Dots, 369 F.3d at 1205-06.

29 See Keystone Mfg. Co., Inc. v. Jaccard Corp., No. 03-CV-648, 2007 WL 655758 (W.D.N.Y., 2/26/2007).

30 Unette Corp. v. Unit Pack Co., 785 F.2d 1026, 1029 (Fed. Cir. 1986); see also Converse, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 909 F.3d 1110, 1124 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (calling the standards “analogous”).

31 TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 29-32; Dippin’ Dots, 369 F.3d at 1205-06.

32 Singer Mfg. Co. v. June Mfg. Co., 163 U.S. 169, 181 (1896); Wal-Mart, 529 U.S. at 213-14; see also Morton Salt Co. v. G.S. Suppiger Co., 314 U.S. 488 (1942) (misuse of patent on machine to restrain unpatented salt tablet sales); Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003) (improper trademark assertion after copyright expiration); Korzybski v. Underwood & Underwood, Inc., 36 F.2d 727, 728-29 (2d Cir. 1929) (election of protection doctrine bars copyright after obtaining patent).