By Steven P. Katkov and Jon Schoenwetter

There has long been a consensus among researchers that single-family zoning is bad for housing affordability, bad for the environment, and bad for racial justice.

— Richard Kahlenberg

Minneapolis is now engaged in the most ambitious urban planning experiment in American history—at once hailed as a promising step to combat rising housing expenses and decried as bulldozing the idyllic American neighborhood. Regardless of sentiment, on January 1, 2020, Minneapolis rezoned approximately 70 percent of its land area in one fell swoop.1 For this, the massive Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Plan is responsible.2 Though the plan has many facets, this article focuses on the zoning code revisions and offers an early assessment of the potential impact for affordability and the built environment.

Minneapolis is now engaged in the most ambitious urban planning experiment in American history—at once hailed as a promising step to combat rising housing expenses and decried as bulldozing the idyllic American neighborhood. Regardless of sentiment, on January 1, 2020, Minneapolis rezoned approximately 70 percent of its land area in one fell swoop.1 For this, the massive Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Plan is responsible.2 Though the plan has many facets, this article focuses on the zoning code revisions and offers an early assessment of the potential impact for affordability and the built environment.

Zoning history

Prior to the 20th century, landowners enjoyed virtually complete autonomy over their real property. Landowners could, of course, consent to restrictions by yielding to informal incentives or drafting private covenants.3 But the only means of restricting offensive uses was common law tort remedies based on nuisance and trespass doctrines. Once sufficient to ensure orderly living, the failure of these doctrines to combat the ills of increasing urbanism and the industrial revolution led social reformers and elected officials to whittle away at freedom of ownership with restrictive legislation and rulings.

Initial movers included Washington, D.C., which enacted height restrictions in 1899, and Los Angeles, which created residential districts in 1908. New York City is often cited as the first to employ comprehensive zoning, with the enactment of, among other restrictions, “wedding-cake” setback requirements responsible for the iconic tiered look of the Chrysler and Empire State buildings.4 In 1916, only eight American cities employed some form of zoning ordinance.5

The desire to zone quickly exploded and, 20 years later, achieved near ubiquity with some 1,254 cities employing it in one way or another, evincing a clear preference for single-use properties and the primacy of the single-family home.6 The US Supreme Court weighed in on the discussion as early as 1909, holding in the case of Welch v. Swase7 that building height restrictions were a constitutional exercise of the police power and laying the foundation for broad police power exercise over land use in 1915 in Hadacheck v. Sebastian.8 With the landmark Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. decision in 1926, the Court unequivocally stamped land-use controls with a resounding seal of constitutional approval.9

Economic, racial, social, and political theories abound, each seeking to explain why land use restrictions developed the way they did. The authors submit that the most compelling explanation is the rise of modern transportation infrastructure. Prior to the last century, most people had little choice but to walk to work and, not surprisingly, favored seeing their immediate neighborhoods develop commercially. Accordingly, our cities were largely a patchwork of uses with homes and businesses in the same area.

Many of the justifications that underlie modern zoning districts arose naturally because of the limited mobility of the workforce. The immense inconvenience and expense of non-foot travel kept higher densities localized. Further, the most noxious of uses—industrial—naturally aggregated around the docks and railyards. Accordingly, distance both caused and insulated naturally occurring residential enclaves.

The early 20th century saw mass proliferation and economization of trolley systems, passenger buses, and, most important of all, the automobile. The urbanite was increasingly free to live in one area and work in another. Trucks similarly unchained industrial structures from the docks and railyards. Enticed by the lower cost of land and liberated by transit, de facto “residential” areas came under assault by the higher densities.10

As people began to live and work in different areas, the development incentive that existed in the live-work neighborhood began to erode. Now the homeowner was able to support downzoning without risking economic ruin. The prospect that an unsavory use could invade a residential neighborhood and depress home values became real. Accordingly, the homeowner had clear economic incentives to re-confine industrial, commercial, and high-density residential back to the transit corridors they had previously occupied. Consequently, zoning codes created zoning districts, dividing the city into areas with similar uses. They provided buffers and transitions between districts with dissimilar uses, such as industrial and residential.11

Affordable housing crisis

Our cities are the product of these zoning practices, and simple intuition indicates that they have had something to do with making our housing so expensive. The growing evidence suggests that (1) the lowest-income renters increasingly outnumber the supply of units they can afford, (2) low-rent stock in most metropolitan areas has declined substantially since 2011, and (3) housing affordability has dropped from 77.5 percent in 2012 to 56.6 percent in 2018.12 This issue seemed to reach a breaking point in 2019, when a flood of new legislation and ideas around housing peppered the public discourse to an unprecedented degree.13 Last year, two states enacted rent control measures to stem the tide of unaffordability among renters.14

While affordable housing means different thing to different people, the HUD definition of “housing with monthly costs that are no more than 30 percent of a household’s income” is a decent place to start. To the average Minneapolitan, this breaks out to approximately $1,400 per month for housing-related expenses.15 In December 2019, the median sales price of a residential property (condominium, townhouse, single-family, new or used, any size, any price) in Minneapolis was $280,000, up approximately $40,000 from two years earlier.16 While more expensive, this home is still “affordable” for the average Minneapolitan.17

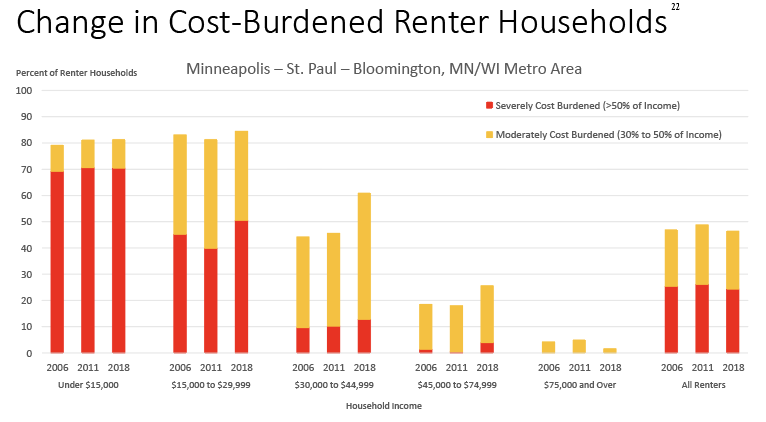

The rental market is somewhat different. The average monthly rent is over $1,500,18 but this figure is slightly misleading, as the market is highly segmented in terms of product. For example, the Star Tribune reported the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment to be $1,847, while the average one-bedroom unit could be had for $1,253.19 Accordingly, the consumer has some control over whether the housing choice they make will be affordable. Regardless, the National Association of Home Builders reports that 45 percent of metro-area renters are “cost burdened,” meaning that they spend more than 30 percent of their pre-tax household income on housing expenses.20 The 30-percent-of-income-standard, while imperfect and no stranger to controversy, presents a real and significant problem for Minneapolis residents.21

Minneapolis 2040 is clearly not just about the “average” Minneapolitan. Indeed, the plan operates on a more expansive idea of affordability: to enable those with less skills and wealth to access the tremendous economic synergies of the Minneapolis area. The ability of Minneapolis 2040 to serve those residents who may make less than 30 percent of the area median income (AMI) has been called into question.23 Currently, the 30th percentile AMI for a single-member household is $21,000; for a four-member household, $30,000.24 Affordability for these households means housing-related expenses of less than $525 and $750 per month, respectively. Between 2011 and 2017, the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan Area lost 35.5 percent of its $800-and-under rental stock, and as such, it’s clear that affordable housing is not occurring at rates commensurate with economic reality.25

The subject is so complex that Gov. Mark Dayton convened a nonpartisan task force in December 2017 to develop solutions to alleviate Minnesota’s housing challenge. The Governor’s Task Force on Housing identified six major themes suggestive of a healthy, affordable housing market, and its final report includes no fewer than 30 action steps aimed at increasing both housing choice and affordability across its 70 pages.26 The report affirms that the state’s building code and regulations need to be transformed to “encourage innovation without sacrificing safety and quality standards.”27 An important driver in the cost of housing in Minneapolis is simply the cost of construction; for a variety of reasons, home construction costs are simply too high in Minnesota to make meaningful progress in this regard.28

Nuts and bolts

Aiming to help reverse this trend, Minneapolis has made a bold declaration through a usually mundane event. By statute, Minnesota cities are required to adopt and update a “comprehensive plan” every 10 years.29 The most recent iteration is Minneapolis 2040, adopted by the City Council on October 25, 2019 and made effective January 1, 2020.

Minneapolis 2040 has 14 goals:

- eliminate disparities;

- more residents and jobs;

- affordable and accessible housing;

- living-wage jobs;

- healthy, safe, and connected people;

- high-quality physical environment;

- history and culture;

- creative, cultural, and natural amenities;

- complete neighborhoods;

- climate change resilience;

- clean environment;

- healthy, sustainable, and diverse economy;

- proactive, accessible, and sustainable government; and

- equitable civil participation system.

By far the most-discussed of these is goal 3, affordable and accessible housing—specifically, the allowance of triplexes on formerly single-family lots. At its core, Minneapolis 2040’s revisions amount to a simple upzoning of residential property. Prior to Minneapolis 2040, the city’s most restrictive zoning, R-1, permitted only one single-family detached structure per parcel. Now, this same zone will accommodate, as of right, three-family attached structures. While simple in concept, its implementation is complex.

On November 13, 2019, Mayor Jacob Frey approved zoning code revisions responsive to Minneapolis 2040.30 The primary revisions are definitional in nature, with “Three-Family Dwelling” largely replacing prior references to single- and two-family items: Three-family dwellings are now permitted in R1-R6 zones.31 Aside from this global modification, the revisions have also coopted variance changes to meet the new three-family dwellings.32 Specifically, Minneapolis may now:

- grant minimum width variance for three-family dwellings located on lots 40 feet or less in width;33

- grant a variance for new enclosed storage requirements;34 and

- grant a variance for curb-cut requirements.35

The revised code also relaxes many existing restrictions in favor of greater density. Some of these changes, like adjusting the per-dwelling minimum lot size requirement, necessarily follow the permission for three-family dwellings.36 Perhaps the most striking change is the abolition of off-site parking requirements. Under the revised code, single-, two-, and three-family dwellings need only provide 200 square feet of enclosed storage, which may or may not be used to house vehicles.37 Also relaxed are the minimum width requirements, from 20 feet to 18 feet,38 and, for many lots, the hard-cover requirement, from 60 to 65 percent.39

Also noteworthy is the new front yard setback mechanic.40 While the revised code maintains the existing front yard setbacks, it provides for an adjustment pursuant to new Sections 546.160(b) and (c). This mechanic allows for reduced front yard setback where the average front yard setback of the majority of residential structures on the same block-face are less than the required distance, provided certain other conditions are met.41 This starkly contrasts with the old code, where front yard setback increased where the immediately neighboring homes were set further back than required.

The revised code also provides for converting existing single-family homes into three-family dwellings.42 Of note, fire escapes and stairs to walk-up units are permitted on the rear exterior of the building (or may be enclosed within). Mechanical boxes must be located on the side or rear of the building and street-facing materials must be comparable to the existing ones. Notably, developers will be permitted to convert already non-conforming single-family structures to three-family dwellings.43

As revolutionary as these changes are, much of the existing regulatory scheme with which developers and homeowners are familiar remain in place and, importantly, Minneapolis did not create one universal residential zone. Accordingly, the differing bulk, yard, and setback requirements still apply to all development. For example, the same three-family dwelling will have to abide by a 25-foot front yard setback on an R1 property and a 15-foot one on an R4 property. In short, develop-ability will vary based on the existing “R” classifications.44 Specifically:

- The design standards remain constant for single-, two-, and three-family dwellings.45

- Height restrictions remain at 25 feet.46

- Rear yard setbacks remain at 5 or 6 feet depending on the R zone.47

- Side yard setbacks remain at 5 to 12 feet depending on lot size.48

- Minimum gross floor area remains at 500 square feet for each dwelling unit.49

- Minimum lot width remains at 50 to 40 feet depending on R zone.50

- Maximum floor area remains at .5x or 2,500 feet.51

Finally, the revised code provides several clarifications regarding egress windows,52 window area requirements,53 and entranceways.54 While the last of these communicates a preference for a shared front entrance, the revised code permits separate entrances, even where two of the three entrances are located on the side of the structure.55

Lack of building code revisions

As indicated previously, the new three-family dwelling presents significant changes for Minneapolis. But Minneapolis 2040 has not produced any meaningful liberalization in building restrictions. Developers will have to abide by the height restrictions and lot line setbacks with which they are familiar. Most importantly, three-family dwellings are not eligible for the height increase mechanism available to single- and two-family dwellings.56 The only notable liberalization is that developers will no longer have to provide off-street parking, though they will have to provide a 10 x 20 foot storage facility instead. No specific revisions to the building code have materialized as of the date of this article, but should be forthcoming this year and beyond.

Long-term policy considerations

The evidence suggests that single-family zoning has contributed to the pattern of ever-increasing housing costs in many American cities. New housing stock has historically either been pushed to neighboring exurbs, increasing automobile emissions and traffic congestion; or it’s been foisted upon poor, minority communities with the effect of gentrification and displacement. This result is by no means unique to Minneapolis but rather is a national phenomenon, where most metropolitan land area is devoted specifically and exclusively to the single-family home.57

Historically, government has enjoyed a number of options to address affordable housing. First, government controls building codes and land use restrictions. To the extent that authorities require more expensive building practices (e.g., Minnesota’s failed residential sprinkler system requirement), housing will likely be more expensive. A similar outcome can be expected where authorities enact zoning ordinances favoring light density. Second, government provides housing subsidies directly to consumers. Such subsidies increase the consumer’s purchasing power, making more of the existing housing stock affordable. Section 8 vouchers are a prominent example. Third, government participates directly in the housing market by constructing units and then renting them at sub-market rates. The Minneapolis Public Housing Authority is one such example. As an operator of nearly 6,000 public housing rental units—including apartment buildings, single-family homes, townhomes, and senior apartment complexes in Minneapolis—it attempts to address affordable housing directly. Finally, government can institute rent control policies that restrict the amounts that landlords can charge. California and Oregon, where rent increases are now capped, respectively, at 5 and 7 percent annually, are examples.

Each of these avenues to affordability comes with consequences. Removing restrictions may lead to greater profits rather than cheaper houses. Rent subsidies merely mask the underlying affordability issue for recipients. Public housing tends to aggregate poverty. Rent control discourages development and pushes housing elsewhere. What is clear amidst this sea of unintended consequences is that our society needs to pull these levers differently if the affordable housing crisis is to be ameliorated. Seen in this light, Minneapolis 2040 is certainly a refreshing initiative.

Theoretically, Minneapolis 2040 paves the way for greater housing supply, which should reduce housing costs. Socially, it promises to reduce racial segregation and promote access to high-opportunity, low-crime neighborhoods. Environmentally, it provides consumers the option to select smaller living footprints and shorter commute times. While these anticipated benefits are largely speculative today, it is clear that forging ahead to more decades of omnipresent downzoning policies is no longer a viable option.58

Looking forward

As a whole, it is difficult to find a single revision to the Zoning Code that will make developing residential property more difficult or expensive. Indeed, the only item that adds to the developer burden is a new tree-density requirement.59 Accordingly, it is easy to conclude that Minneapolis 2040 is more development-friendly than many of its critics have insisted. Yet we also have substantial justification for concluding that, over time, the liberalization of restrictive single-family zoning will create more affordable housing.

Setting aside limited developments in the last decade, a strong case can be made that we live under the most restrictive, down-zoned regimes in the nation’s history. These restrictions contribute to costs that, according to the National Association of Home Builders, account for 25 percent of the sticker price on new single-family homes.60 There is undebatable merit in zoning and building codes that promote quality of living, health, and safety. Today’s big question is not whether our codes meet these goals, but whether they are detrimentally excessive. Minneapolis 2040 answers affirmatively. Indeed, if the plan stands for anything, it’s that we can no longer ignore the value of supply-driven solutions as part of an effective regulatory system.

It is, however, unlikely that the triplexes contemplated by Minneapolis 2040 will be, in and of themselves, “affordable” housing units. Indeed, the authors believe it would be unrealistic to expect new triplexes in Minneapolis for less than $250,000 per unit in the existing marketplace. To the extent that this upzoning initiative does impact area affordability, it will take time.

In the near term, the authors expect that upzoning will have little tangible impact on affordability. Indeed, a recent study in Auckland, New Zealand revealed that upzoning actually increases the cost of housing as existing lots are repriced according to their new development value.61 Following these results, Minneapolis’ single-family lots with older, smaller homes will see noticeable price increases as developers compete for initial triplex pads.62

These triplexes will likely serve two demographics—first, young professionals looking to secure more space who are either unwilling to forego the ease-of-use that flows from professional property management or unprepared to purchase a single-family home; and second, existing homeowners who are looking to right-size their living footprint but are unwilling to accept high-density living. Neither of these groups is among the “less well-off” demographics that Minneapolis 2040 clearly aims to fight for.

As the market for triplexes begins to mature, there is ample reason to believe these initial price increases will be offset by the growing availability of housing stock. First, triplex residents become removed from the marketplace. In sufficient numbers, this will help readjust vacancy rates back to historic levels and give landlords more incentive to reduce rents. Second, it is expected that many new triplex residents will be moving from existing single-family homes. This will assist the existing homes in “filtering down” and, given sufficient numbers, becoming viable candidates for triplex redevelopment themselves.63 Most promisingly, Minneapolis 2040 offers to bring down housing costs in affluent areas and allow more people to access the localized opportunities there. This objective is something that traditional programs, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit or Housing Choice Voucher System, have struggled to do. Indeed, a 2012 RAND study found that only 10 percent of housing created through the LIHTC program, and 7 percent under the choice voucher program, are located near low-poverty-rate schools.64

It is simply true that subject to structure, quality, and location, large houses on big lots cost more to buy or rent than smaller ones. Though it’s necessarily still hypothetical, simple math suggests that the opportunity to replace a single unit with three dwelling spaces militates in favor of increasing the available housing stock. So in time we can reasonably expect triplex units to be more affordable than comparably finished and located single-family homes. By permitting Minneapolitans to go smaller, Minneapolis 2040 offers a previously unavailable way to reduce housing costs. While it’s clearly not a panacea for our city’s housing crisis, it is a step that, in conjunction with other measures, will aid in the cure.65

STEVEN P. KATKOV is a partner in the real estate practice group of Cozen O’Connor. He has a diverse real estate practice of a national scope and is a leading cannabis attorney. Steve is a graduate of the University of Minnesota Law School, where he served as the managing editor of the Law and Inequality Journal.

JON SCHOENWETTER is an associate in the real estate practice group of Cozen O’Connor, working on all manner of real estate transactions around the nation. Jon is a graduate of the University of Minnesota law school, where he published an article in the Law and Inequality Journal on the subject of diversity in the granting of municipal contracts by the City of Minneapolis.

Notes

1 Richard D. Kahlenberg, How Minneapolis Ended Single-Family Zoning (The Century Foundation, 10/24/2019) (identifying approximately 70% of Minneapolis’ land area as reserved for single-family residential use), https://tcf.org/content/report/minneapolis-ended-single-family-zoning/?agreed=1

2 Weighing in at roughly 1,250 pages replete with studies, Minneapolis 2040 may be found online here: https://minneapolis2040.com/.

3 Notably, rudimentary zoning restrictions, often related to fire safety, can be traced to the 19th century. See e.g., William A. Fischel, An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for Its Exclusionary Effects 13 (12/18/2001). https://www.dartmouth.edu/~wfischel/Papers/02-03.pdf

4 Fischel, at 3.

5 Elizabeth Winkler, ‘Snob Zoning’ is Racial Housing Segregation by Another Name, Wash. Post (9/25/2017). https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/09/25/snob-zoning-is-racial-housing-segregation-by-another-name/

6 Id. (with ordinances on the books in 1,254 cities).

7 214 U.S. 91 (1909).

8 239 U.S. 394 (1915) (holding that cities may restrict uses without committing a 5th Amendment taking).

9 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

10 Fischel, at 15 (“”[N]ew modes of transportation allowed people to separate where they lived from where they worked and… the development of the bus and truck undermined traditional means of protecting neighborhoods.”).

11 Indeed, a segregating effect was and is clearly the goal of zoning ordinances. See, e.g., Gabriel Metcalf, Sand Castles Before the Tide? Affordable Housing in Expensive Cities, 32 J. of Econ. Perspectives 69, n. 1 (Winter, 2018) (“[F]or the country as a whole, the restrictive housing policies of the cities in expensive metro areas leads to the segregation of the wealthy into zoned enclave communities; a reduced ability of lower-income people to move to areas of higher opportunity; a diversion of enormous wealth into rent-seeking behavior by landowners; and a decrease in economic productivity for the country as a whole, because labor is not able to be allocated to the most productive economic clusters.”). While segregating uses seems morally neutral, ordinance drafters rather quickly realized that zoning could be used for a more nefarious purpose: segregating people. For example, one of the first implementations of zoning in the county—Baltimore’s 1910 ordinance—prohibited selling or renting property in majority-white neighborhoods to blacks, and vis versa. Silver, at 1. The prevalence of race-based zoning continued until the Supreme Court struck down a Louisville, Kentucky law similar to the Baltimore ordinance in 1917. See Buchannan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) (holding the ordinance violated the freedom to contract under the 14th Amendment). With affirmative race-based exclusionary zoning policies “out,” in stepped the proxy of private deed covenants, later struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). While it would be disingenuous to suggest that this narrative is the only explanation for the early-century explosion in zoning practice, it was undeniably an early and significant force.

12 Source: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, available at: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/data-and-charts/?ra=affordability.

13 See, e.g., Richard Florida, How Housing Supply Became the Most Controversial Issue in Urbanism (Citylab, 5/23/2019), https://www.citylab.com/design/2019/05/residential-zoning-code-density-storper-rodriguez-pose-data/590050/); Richard D. Kahlenberg, Minneapolis Saw That NIMBYism Has Victims (The Atlantic, 10/24/2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/10/how-minneapolis-defeated-nimbyism/600601/ ; Laura Kusisto & Peter Grant, Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (Wall St. J., Apr. 2, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/affordable-housing-crisis-spreads-throughout-world-11554210003; Alcynna Lloyd, NAHB: Most Homeowners now view Housing Market’s Affordability Problem as a Crisis (Housing Wire, 9/13/2019), https://www.housingwire.com/articles/50149-nahb-most-homeowners-now-recognize-the-housing-markets-affordability-problem-as-a-crisis/ The issue has even inspired the creation of a White House Council to study it. See Exec. Order No. 13878, 84 C.F.R. 30853.

14 Oregon and California are the first to employ state-wide rent control. Jenna Chandler, Here’s How California’s Rent Control Law Works (Curbed Los Angeles, 1/6/2020), https://la.curbed.com/2019/9/24/20868937/california-rent-control-law-bill-governor; Lauren Drake, Rent Control is Now The Law In Oregon (Oregon Publ. Broad., 2/28/2019), https://www.opb.org/news/article/oregon-rent-control-law-signed/ New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and Washington D.C. all have some form of local level rent control. National Multifamily Housing Council, Rent Control Laws by State (NMHC, 9/20/2019).

15 US Census Bureau, QuickFacts: Minneapolis City, Minnesota (U.S. Census Bureau, 7/1/2018) (reporting median household income as $55,270 in 2017 dollars). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/minneapoliscityminnesota

16 NorthstarMLS, Infosparks Market (10K Research, 1/13/2019).

17 Submitting that $1,400 per month can sustain a $300,000 thirty-year, fixed-rate mortgage at 4 percent.

18 RentCafe, Minneapolis, MN Rental Market Trends (Sept., 2019). https://www.rentcafe.com/average-rent-market-trends/us/mn/minneapolis/

19 C.J. Sinner, How Much is Rent in Twin Cities? This Guide Breaks it Down by Area, Unit Type (StarTribune, 6/14/2019). http://www.startribune.com/how-much-is-rent-in-twin-cities-this-guide-breaks-it-down-by-area-unit-type/414996293/

20 National Association of Home Builders, Housing Fuels the Economy (NAHB, 2019). http://www.nahbhousingportal.org/states/minnesota/?tab=afford

21 Christopher Herbert, Alexander Hermann & Daniel McCue, Measuring Housing Affordability: Assessing the 30-Percent of Income Standard (Joint Ctr. For Housing Studies, Sept., 2018). http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_Herbert_Hermann_McCue_measuring_housing_affordability.pdf

22 Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2006–2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates using the Missouri Data Center MABLE/geocorr14, available at: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/son-2019-cost-burdens-map.

23 Jack Cann, Objections to Minneapolis Draft Comprehensive Plan (1/22/2019). https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6024160-Objections-to-Minneapolis-Draft-Comprehensive-Plan.html

24 NeighborWorks Home Partners, Area Median Income, (NeighborWorks Home Partners, 2019).

25 Joint Center for Housing Studies, The Low-Rent Stock in Most Metros has Declined Substantially Since 2011 (Joint Ctr. For Housing Studies, 2019) (adjusting contract rents and household income to 2017 dollars).ttps://

26 Minnesota Legislature, Governor’s Task Force on Housing (Minn. Legis. Ref. Libr., 8/21/2018), https://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/agencies/detail?AgencyID=2312

27 Governor’s Task Force on Housing, More Places to Call Home: Investing in Minnesota’s Future 25 (8/21/2018), https://www.leg.state.mn.us/docs/2018/other/180809.pdf

28 Housing First Minnesota, Solutions to the High Cost of Housing in Minnesota (2019) (noting that 2018 legislation had increased the cost of producing a new single-family home in Minnesota by $17,000). https://www.mnhousingtaskforce.com/sites/mnhousingtaskforce.com/files/media/25.%20Housing%20First%20reply%20to%20Call%20for%20Ideas.pdf

29 Minn Stat. §473.85171 (Metropolitan Land Planning Act).

30 Minn. Ord. No. 2019-048 (11/16/2019), https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/Download/MetaData/15355/2019-048_Id_15355.pdf The Minneapolis Code of Ordinances can be accessed online here: https://library.municode.com/mn/minneapolis/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=MICOOR_TIT20ZOCO#TOPTITLE.

31 Id., at T. 546-1.

32 We presume that the legal standards applicable to the granting of a variance under Minnesota law will apply to this section of the plan, permitting affected property owners to oppose any variance request under Minn. Stat. Section 462.357 and its case law. If true, the plan’s effectiveness could be limited by disqualifying more challenging lots from consideration because the property owner cannot reasonably demonstrate that strict enforcement would cause the owner “practical difficulties.” See In re Stadsvold, 754 N.W.2d 323 (Minn. 2008). The authors predict that any variance applications under Minneapolis 2040 will be met with vocal public opposition.

33 Id., at 525.520(12).

34 Id., at 525.520(30).

35 Id., at 525.520(31).

36 Id., at T. 546-3 “Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (providing that single, two-, and three-family dwellings must have a minimum lot area of 6,000 feet); T. 546-5 “R1A Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (providing a minimum lot area of 5,000 feet); T. 546-7 “R2 Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (same); T. 546-9 “R2B Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (same).

37 Id., at 530.300.

38 Id., at 535.90.

39 Id., at 546.150(b) (if the lot does not have second street frontage or access to a public alleyway, and is less than 6,000 square feet, hard cover is permitted on 65% of the lot).

40 Id., at 546.160(c).

41 Id., at 546.160(c)(1)-(2) (no fewer than four residential structures on same block face; setback not less than the two immediate side neighboring residential structures).

42 Id., at 535.90(e)

43 Id., at 535.90(f) (provided that the nonconformance is not increased).

44 Id., at 546.200 et. seq.

45 Id., at 530.280.

46 Id., at 546.110 (33 feet at highest point).

47 Id., at T. 546-2 “R1 Yard Requirements” (6 feet); T. 546-4 “R1A Yard Requirements” (same); T. 546-6 “R2 Yard Requirements” (same); T. 546-8 “R2B Yard Requirements” (same).

48 Id. (5 feet for lots less than 42 feet; 12 for lots in excess of 100 feet).

49 Id., at 535.90 (350 feet for studio units).

50 Id., at T. 546-3 “R1 Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (50 feet); T. 546-5 “R1A Lot Dimensions and Building Bulk Requirements” (40 feet); Table 546-6 “R2 Yard Requirements” (same); T. 546-8 “R2B Yard Requirements” (same).

51 Id.

52 Id., at T. 535-1 (providing that egress windows must be at least 3 feet apart and not more than 3 egress wells may project closer than 5 feet to an interior side lot line).

53 Id., at 535.90(c).

54 Id., at 535.90(b)(1).

55 Id., at 535.90(b)

56 Id., at 546.240(f) (proving that “the maximum height of single- and two-family dwellings may be increased...”) (emphasis added).

57 Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: a House With a Yard on Every Lot (N.Y. Times, 6/18/2019) (“It is illegal on 75 percent of the residential land in many American cities to build anything other than a detached single-family home.”). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html

58 Consider Los Angeles, which, despite increasing population, has lost 60% of its population capacity to downzoning between 1970 and 2010. Gregory D. Morrow, The Homeowner Revolution: Democracy, Land Use and the Los Angeles Slow-Growth Movement, 1965-1992, ii (2013). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6k64g20f

59 Minn. Ord. No. 530.295 (requiring one tree for every 3,000 feet of lot area).

60 National Association of Home Builders, Housing Fuels the Economy (NAHB, 2019). http://www.nahbhousingportal.org/

61 Ryan Greenway-McGrevy, Gail Pacheco & Kade Sorenson, Land Use Regulation, the Redevelopment Premium and House Prices, 2 (Univ. of Auckland: Economics Working Paper Series, Sept. 2018). https://www.aut.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/163542/AUT_wp_2018_02_updated.pdf

62 Id., at 12.

63 Stuart S. Rosenthal, Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing? Estimates from a “Repeat Income” Model, 104 Am. Econ. R. 104, 687, 704 (2014); John C. Weicher, Frederick J. Eggers & Fouad Moumen, The Long-Term Dynamics of Affordable Rental Housing 3 (Hudson Inst., 9/15/2017) (“Filtering added 4.6 million units to the affordable rental inventory and gentrification removed 1.7 million, for a net contribution of 2.9 million units to the affordable rental housing stock [between 1985 and 2013].”). https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.hudson.org/files/publications/AffordableRentHousing2017.pdf

64 Hickey, at 4.

65 For those new to the discussion of duplex and triplex construction on single-family lots, the idea is neither novel nor recent. As early as the 1980s, the town of Chester, New Hampshire battled this very issue with an enterprising developer, Raymond Remillard. Chester had a zoning ordinance, in effect since 1985, that provided for a single-family home on a two-acre lot, a duplex on a three-acre lot and excluded multi-family housing from all five zoning districts. Remillard owned 23 acres and tried for 11 years to obtain a permit to construct a multi-unit housing complex primarily for low- to moderate-income families. He ultimately succeeded in his quest when the New Hampshire Supreme Court struck down Chester’s exclusionary zoning ordinance as unconstitutionally restrictive, evincing a clear prejudice “for people who can afford a single-family home on a two-acre lot or a duplex on a three-acre lot.” See Britton v. Town of Chester, 595 A.2d 492 (N.H. 1991).