By Stephanie Angolkar

One October morning in 2021, I prepared to return to in-person oral arguments before the Eighth Circuit in St. Paul, Minnesota. After checking in for my argument, I entered the courtroom and quickly saw that I was the only woman in the room. That only changed when the court clerk entered at the start of arguments. The panel clearly had been looking forward to returning to in-person arguments and was very active.

Appellate attorneys often sit in the gallery during the arguments of other cases. One of the cases argued was the appeal of a sex trafficking conviction, United States v. Taylor.1 The engaged panel asked questions about the meaning of a “happy ending.”2 These questions, which can be listened to online, addressed such details as the placement of a hand towel and other hypotheticals. I do not need to tell you the panel was all-male because you know the odds of that in the Eighth Circuit—where we have only one female judge.

So there I sat, trying to identify this feeling I was experiencing. It was a sensitive case, so of course they would need to ask some sensitive questions about the details, right? But I could not help wondering, would the makeup of this audience before the court change the way the questions were asked? The very detailed hypotheticals? Then I started to wonder how these questions might change if there were a woman arguing. Would they be asked the same way? And what if there was a woman among the three judges? Would the questions change? Would they be asked differently? Then my thoughts turned even bolder: What if there were three women on the panel?

The argument ended, and it was time to leave. I pushed the thoughts and questions about more women on the bench aside. But the argument that morning started me on a quest to join a long-standing argument regarding the need for more women on the Eighth Circuit.

Gender balance in the courts

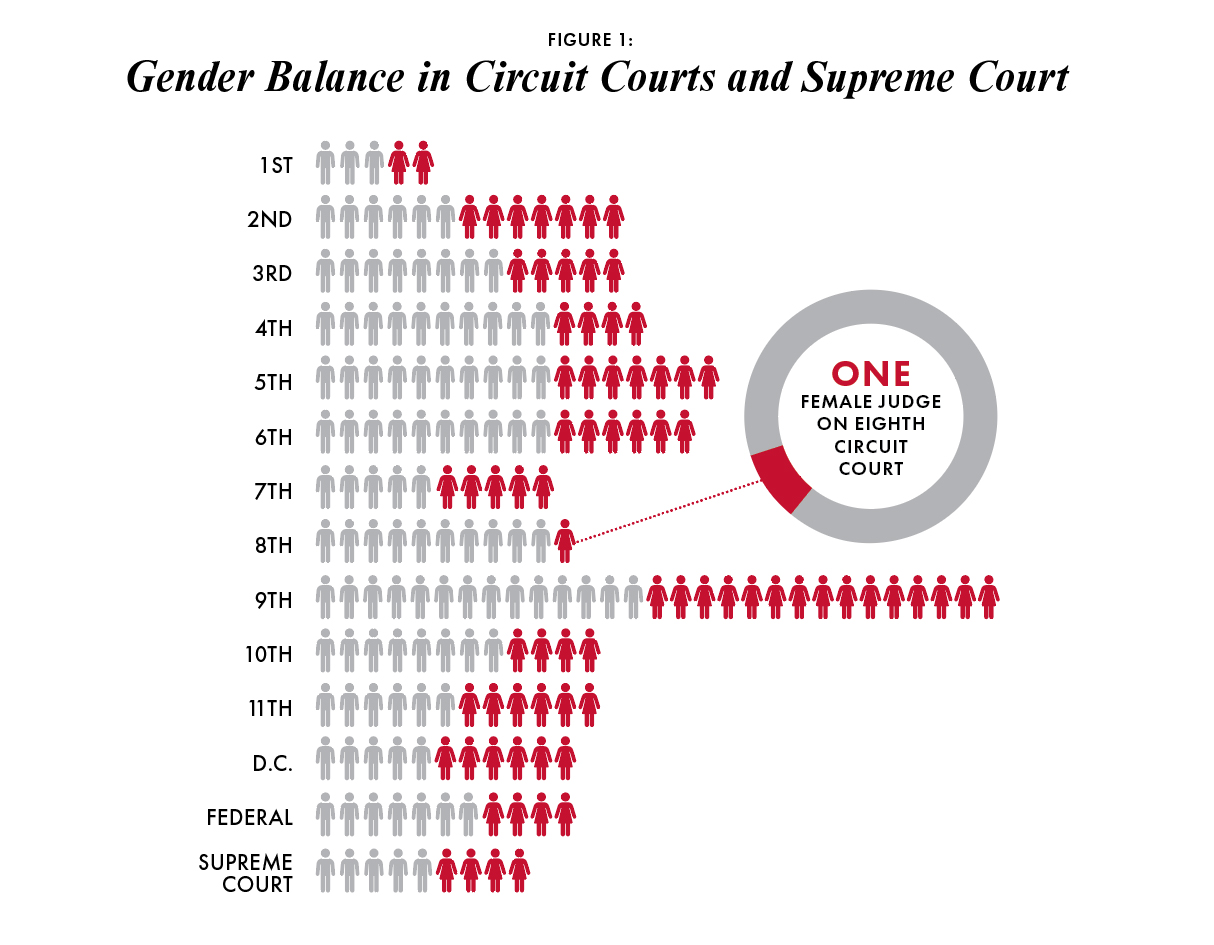

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals has only one female judge. In its history, only two women have served: Judge Diana Murphy (deceased) and Judge Jane Kelly. Since Judge Kelly’s appointment in 2013, four white men have been appointed. In contrast, other Circuit Courts of Appeal reflect more gender balance (see Figure 1).

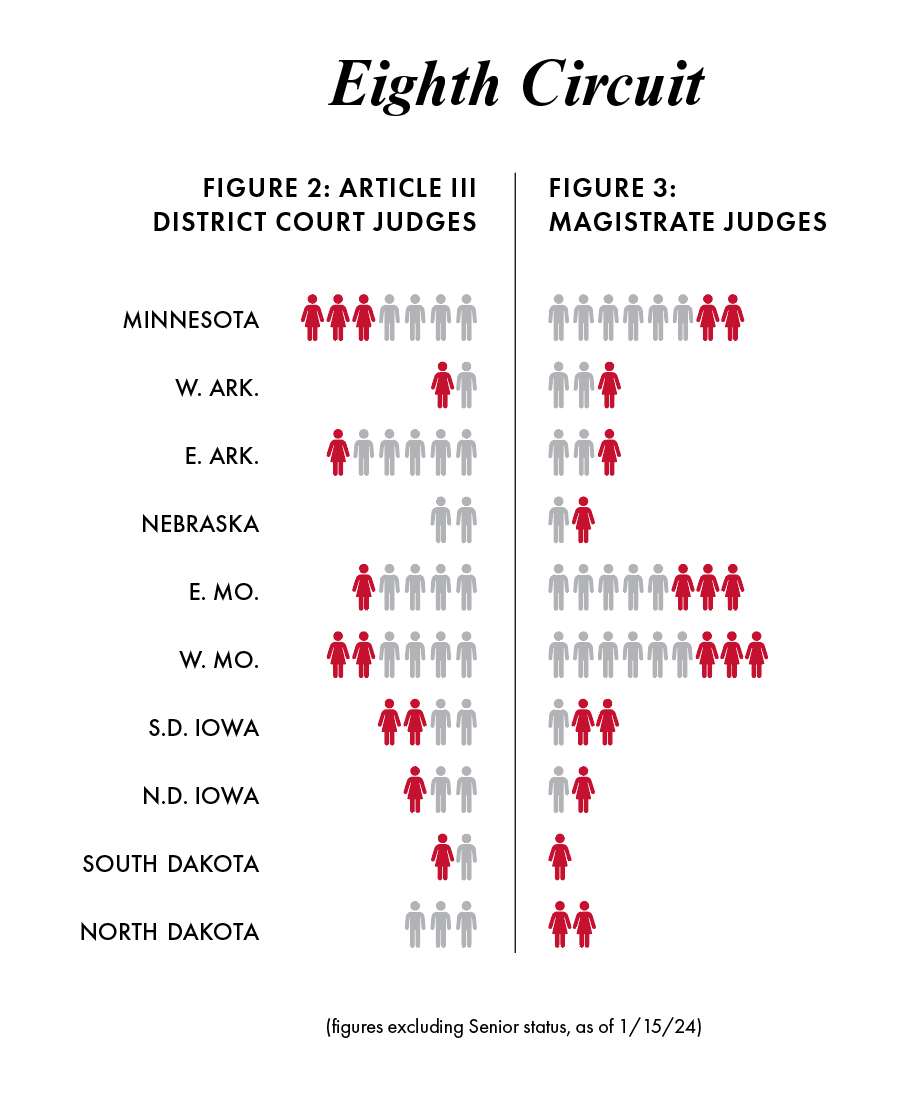

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals serves the region including North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas. Within those states’ federal district courts, too, there is still work to be done to improve gender balance (see Figure 2).

At the magistrate judge level, gender balance in the states within the Eighth Circuit is progressing (see Figure 3).

In some cases, a woman’s perspective can influence the result. In Safford Unified School District v. Redding,3 a case involving the strip-search of a 13-year-old-girl, the Supreme Court justices questioned the seriousness of the charge during oral arguments. Only Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg expressed deep concern. Justice Ginsburg is believed to have influenced the eventual 8-1 vote, and she later explained, “They have never been a 13-year-old girl.”4

There are many studies and resources analyzing the impact of gender on decisions of the courts.5 A diverse bench also improves public confidence in the courts. There is something powerfully affirming for the public in seeing judges that look like them or have a relatable background.

The Infinity Project

The argument for more women in the Eighth Circuit was amplified in 2007. That year, Judge Mary Vasaly, Marie Failinger, Lisa Brabbit, and Sally Kenney founded The Infinity Project in Minnesota. Their mission was to increase gender diversity on the Eighth Circuit bench. The Infinity Project believes it is necessary to have a bench reflecting society as a whole so that judicial decisions take into account varied life experiences and points of view.

The Infinity Project has a busy Applicant Support Committee, recently honored with a Minnesota Lawyer Attorneys of the Year award for diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. This committee assists women applying for judicial positions, whether it be brainstorming sessions, application and cover letter feedback, or mock interviews.

The committee works with women and diverse candidates applying for judgeships at state and federal levels in multiple states within the Eighth Circuit. The Infinity Project hopes its efforts supporting women at multiple levels will grow the pipeline to the Eighth Circuit--and that these efforts could be more formally replicated in other states. This is particularly important since federal judges often have prior judicial experience. For example, the Hon. Wilhelmina Wright served at all levels of the judiciary in Minnesota before her appointment by President Biden to the United States District Court of Minnesota, and she was a strong contender when he considered an appointment to the United States Supreme Court.

Let’s think, too, about the demographics of who is appearing before the court. Are there concerns about the legitimacy of courts and the ethics of judges? How does it feel to appear in a judicial system that more accurately reflects the diversity of our communities? When there is more balance, it feels like a system working for all of us, resulting in more trust from all of us.

I speak from my own perspective as a female attorney. I treasure a moment from a jury trial several years ago in which I, female co-counsel, female opposing counsel, and Judge Ann Montgomery were addressing a trial matter outside the presence of the jury. I do not even remember what it was about. What stands out to me is that we were all women in the courtroom at that time. It is a moment I have yet to replicate in practice. When I appear before a woman judge or am working with other women attorneys in my heavily male-dominated practice area, there is a boost in my self-esteem that affirms and validates my presence in this profession and practice area.

Lived experiences have an impact on judicial philosophies. And the makeup of our bench has an influence on those appearing before it, their trust in the system, and their own feelings of self-worth and possibility.

At a time when diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are under attack, it is important to reflect on why these efforts are important. It is not about evening out numbers or meeting a ratio, though certainly data points help. Rather, if we view a judicial branch that more closely reflects the diversity of our society, we add legitimacy, buy-in, and ownership by the public in this system.

How you can help

If you are curious to learn more about the Infinity Project, visit www.theinfinityproject.org/minnesota. The Infinity Project is a nonpartisan organization that relies on donations from granting agencies, law firms, and individuals to cover expenses for the volunteer-based organization.

Stephanie Angolkar is a partner at Iverson Reuvers in Bloomington, Minnesota, who regularly handles appeals before the Eighth Circuit and trials in federal and state court in civil rights and complex civil litigation matters. She is president of The Infinity Project, based in Minnesota. She is also an MSBA-certified civil trial law specialist.

Notes

1 44 F.4th 779 (8th Cir. 2022).

2 This was one of the issues raised in the appeal. The court affirmed the jury’s conviction of sex trafficking offenses.

3 557 U.S. 364 (2009).

4 Hayes, Hannah, Diversity on the Bench: Why It Matters in a Polarized Supreme Court, American Bar Association, (8/17/2022), (available at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/diversity/women/publications/perspectives/2022/august/diversity-the-bench-why-it-matters-a-polarized-supreme-court/).

5 See, e.g. Haire, Susan and Laura Moyer, Gender, Law, and Judging, Oxford Research Encylopedias, (4/26/2019) (available at: https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-106#:~:text=In%20an%20analysis%20of%20sex,recent%20cohorts%2C%20the%20effect%20disappears.