By Bryce Riddle and Kyle WillemsSpecial purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) are shell companies that raise capital in initial public offerings for the purpose of merging with or acquiring a privately held company. While SPACs are nothing new, they are being hailed as the next big thing in the securities industry. And with good reason: Over the past few years, the number of SPAC listings have skyrocketed in the United States. In 2019, 59 SPACs were created, with $13 billion invested; in 2020, 247 were created, with $80 billion invested; and in 2021, 613 were created, with $145 billion invested.1

As SPACs have gained popularity, public opinion has started to view them as a better alternative to traditional IPOs. With sponsors ranging from venture capitalists to celebrities, all signs indicate that SPAC investment will continue to rise. But, not surprisingly, SPACs’ rise in popularity has coincided with an increase in SPAC-related litigation—and this trend is not expected to slow anytime soon. This article examines what SPACs are and discusses current legal trends that have arisen in the SPAC space.

History

SPACs first appeared as “blank check” corporations in the 1980s and were not well regulated. They were often associated with penny-stock fraud and cost investors more than $2 billion by the early 1990s. Congress ultimately enacted much-needed regulation, such as requiring that the proceeds of blank-check IPOs be held in regulated escrow accounts and barring their use until the mergers were complete.2 With a new regulatory framework in place, blank-check corporations were rebranded as SPACs.

In the decades that followed, SPACs became a cottage industry for boutique law firms, auditors, and investment banks to support sponsor groups that lacked national recognition or investment training. But that changed in 2019, when investors began launching SPACs in significant numbers. Established hedge funds, private-equity and venture firms, and senior operating executives were all drawn to SPACs for various reasons, including:

- excess available cash;

- a proliferation of start-ups seeking liquidity or growth capital;

- regulatory changes that standardized SPAC products; and

- the ability to help private companies go through the IPO process on an expedited timetable and with less regulatory oversight.

Investors, too, have flocked to SPACs, enticed by the excitement of investing with a favorite brand name investor or celebrity, unique redemption rights, and the possibility of high returns.

As expected, the pros have not come without cons. Growing criticisms include:

- fee arrangements that can create competing interests between sponsors and shareholders;

- high failure rates (including the failure to merge with targets and a high overall fail rate);

- a lack of transparency;

- imbalance between the protections afforded to sponsor and shareholder rights; and

- conflicts of interest between SPAC sponsors and shareholders.

To better understand current trends in SPAC litigation, it is helpful to understand how a SPAC operates, who the interested parties are, and the goals of each party over a SPAC’s lifecycle.

Sponsors, shareholders, and target companies form the core group of stakeholders in any SPAC transaction, each with distinct goals and perspectives. Sponsors initiate the SPAC process by investing risk capital in the form of nonrefundable payments to bankers, lawyers, and accountants to cover operating expenses while the SPAC searches for target companies to acquire. If the SPAC fails to effectuate a combination within a set time frame (almost always two years), the SPAC must be dissolved and the sponsors lose their risk capital.

Shareholders invest in a SPAC once it goes public, but before a target company has been identified. From there, the shareholders trust the sponsors to locate an appropriate target company. After the sponsor announces an agreement with a target company, the shareholders vote on whether to move forward with the deal or cash out a pro rata share of the funds that remain in the SPAC’s trust account, with interest.

Target companies are typically start-up firms that have been through the venture capital process and are looking to grow. At this stage, SPACs are attractive due to their customization and time to market, assuming the target company’s business and financials are in order.

SPAC lifecycle

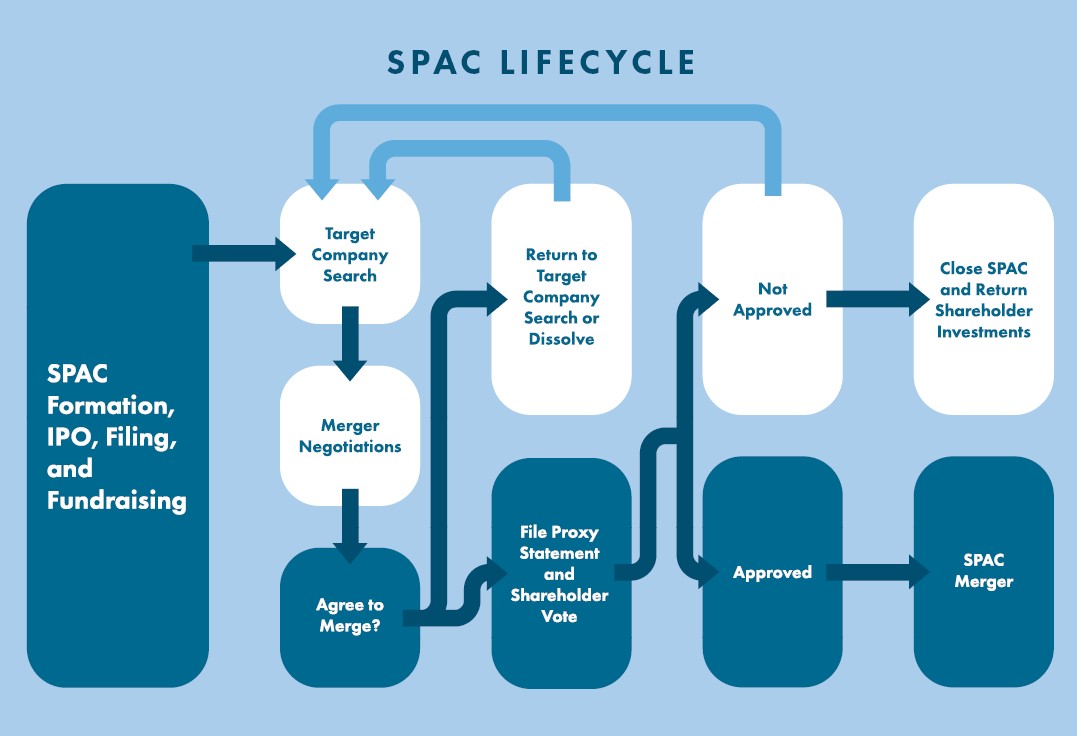

A typical SPAC has four phases in its life cycle: formation, target search, shareholder approval, and merger. Below is a timeline of a typical SPAC’s life cycle.

SPAC formation

SPACs start as a concept. These concepts are brought to life by a sponsor who creates a SPAC IPO plan, invests risk capital for operating expenses, and announces a board of directors. A SPAC’s IPO plan is typically based on an investment thesis focused on a sector and geography, such as the intent to acquire a media company in North America, or a sponsor’s experience and background. The risk capital invested often translates to an approximate 20 percent interest in the SPAC and is commonly referred to as founder shares.

The SPAC then goes through the typical IPO process. Sponsors staff the SPAC operations team with underwriters, file an IPO registration statement with the SEC, clear SEC comments, and seek to raise capital from shareholders. Because SPACs have no historical financial results to disclose or assets to describe, SPAC financial statements in the IPO registration statement are very short and can be prepared in a matter of weeks. In essence, the IPO registration statement is mostly boilerplate language—aside from the typical practice of vaguely identifying the industry in which the target company might be operating.

Investment in SPACs during IPO phase

During the initial public offering, shareholders are sold “units” that comprise one share of common stock and, typically, a fraction of a warrant to purchase a share of common stock in the future. A full warrant, or multiple warrants per shareholder, may be issued to entice shareholders to buy into a SPAC that may be perceived as particularly risky. Nearly all SPACs sell units for $10. Following the IPO, the units become separable so that the public can trade units, shares, or whole warrants, with each security separately listed on a securities exchange.

Search for target companies begins

Following the IPO process, proceeds are placed into a trust account. At this stage, the SPAC typically has up to 24 months to identify and complete a merger, seek an extension, or return all invested funds to shareholders, at which point the sponsors typically lose their founder shares and risk capital. The SPAC management team begins discussions with privately held companies that may be suitable merger targets.

Raise additional capital, if necessary

Once a SPAC and target company reach an agreement to merge, additional funds may be required to consummate the purchase. If the situation so demands, the SPAC then attempts to validate the target company’s valuation and raise additional funds in a private investment in public equity (PIPE) funding.

Finalize terms of the merger

Once all funds are secured, the SPAC and target company file a proxy that outlines the financial history of the target along with merger terms and conditions.

Hold shareholder vote on merger

Once the proxy statement is filed, the SPAC’s public shareholders must then approve the transaction or elect to redeem their shares. The proxy statement will contain various matters seeking shareholder approval, including a description of the proposed merger and governance matters. It will also include financial information of the target company, such as historical financial statements, management’s discussions and analysis, and pro forma financial statements showing the effect of the merger.

Complete the merger

If the deal is approved, the merger is completed shortly thereafter using the assets remaining after any withdrawals. The SPAC and PIPE proceeds are invested in the target company, the governance structure of the SPAC is dissolved, and the target starts trading under its own name and ticker symbol.

Recent trends in litigation

Unfortunately, not all stakeholder incentives are perfectly aligned, and litigation ensues. Data indicates that as SPAC usage increased, so too did litigation.

| Year | SPACs Created3 | SPAC-Related Federal Class Action Filings4 |

2019 | 59 | 1 |

2020 | 248 | 5 |

2021 | 613 | 32 |

A review of SPAC-centered lawsuits shows that most claims, whether brought by a class or not, fall into two broad categories: misrepresentations in financial documents and breach of fiduciary duties.

Misrepresentation and omission in financial documents

Common law and statutory claims for misrepresentation are the driving force for SPAC-related litigation. Typically, these claims arise out of allegations that a SPAC and/or its sponsors made material misrepresentations or omissions in the initial registration statement, the proxy statement, post-merger statements, other formal statements, Securities and Exchange Commission filings, or SPAC-related agreements.

Claims for misrepresentations and omissions are often brought under a combination of typical common law claims (including negligence, breach of contract, etc.) and various statutory claims—most notably those set forth in the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. The tip of the spear tends to be alleged violations of Section 14(a) (a cause of action that is narrowly limited to the truthfulness and accuracy of representations that relate to proxy statements, with a requirement that the defendant acted negligently) and Section 10(b) (a cause of action that broadly relates to the truthfulness and accuracy of representations that relate to publicly traded securities, which requires both a showing of negligence and scienter).5

There is little litigation surrounding a SPAC’s initial registration statement. This makes sense, given the fact that SPACs are “blank check” companies that are allowed to have initial registration statements that can contain nothing more than a vague statement about the SPAC’s purpose. The bulk of SPAC-related litigation concerns alleged misrepresentations and omissions in the proxy statement, which is the first substantial document that shareholders rely on when voting on the merger. Claims that arise out of the proxy statement tend to fall into two camps: those that arise before the merger and those that arise after.

Claims made pre-merger are often easy to dispatch of by revising the proxy statement to correct alleged misrepresentations or omissions. This renders claims moot, and the SPAC and/or its sponsors will pay a settlement that Wall Street litigators colloquially refer to as a “mootness fee.”6

More problematic for SPACs and their sponsors are post-merger misrepresentation and omission claims that relate to the proxy statement. These tend to relate back to alleged misrepresentations and omissions made in the proxy statement, and a common theme is that they arise when plaintiff-shareholders have buyers’ remorse because they are not getting the return on investment they hoped for. Two well-known examples of this happening are In re Heckmann Corporation Securities Litigation7 (commonly referred to as the “China Water” case) and Welch v. Meaux8 (commonly referred to as the “Waitr” case).

In the China Water case, the plaintiffs-shareholders asserted Section 10(b) and 14(a) claims (among other claims) based on allegations that the proxy statement misstated the target’s (China Water and Drinks, Inc.) operations and financial wellbeing. After three and a half years of complex and expensive litigation, the China Water case settled for $27 million.

The China Water case is a particularly important SPAC lawsuit, because it resolved well before the SPAC boom kicked off in 2019. It sent a message that SPACs would not be immune from complex, expensive litigation if proper disclosures were not made—particularly via the proxy statement.

The Waitr case came several years after the China Water case, during the current SPAC boom. In the Waitr case, plaintiffs sued under Section 10(b) (among other claims) on allegations that there were material deficiencies with the SPAC’s proxy statement and the post-merger registration statement. Specifically, the plaintiffs allege that they were not properly informed of known risks and that the target company’s financial valuation was inflated.9

The Waitr case built on the lessons learned in the China Water case and highlighted some additional issues that SPACs face. While SPACs may be able to dash through the IPO process with less overhead and scrutiny, the failure to perform sufficient due diligence and make proper disclosures may mean aggrieved plaintiff-shareholders will look to key representations made by sponsors, officers, directors, and the SPAC, such as those made in the proxy statement, to create an avenue to recovery if the SPAC does not make returns as expected.

Breach of fiduciary duties

SPAC-related breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims are also common, and SPAC sponsors, officers, and directors are closely tracking legal developments, because a successful breach of fiduciary duty claim means a finding of personal liability.

Typically, these claims arise out of allegations that officers and directors violated the duties of loyalty and due care (among other duties, depending on the situation) that they owe the corporation and its shareholders. Often, officers and directors respond to breach-of-fiduciary claims by citing a variety of protections, such as those afforded to them by the business judgment rule and contractual exculpatory clauses.

Given the broad protections afforded to officers and directors, breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims often take a back seat in SPAC-related litigation and there has not been a bevy of fiduciary duty lawsuits as of late.

But that may be changing. The SPAC world has been closely tracking the case of Kwame Amo v. MultiPlan Corp, et al.10 In Kwame Amo, the plaintiff-shareholders alleged that the sponsor, officers, and directors created a compensation structure for themselves that incentivized them to get the SPAC at issue to merge—even if the resultant merger was detrimental to the plaintiffs-shareholders.11 The plaintiff-shareholders also alleged that the sponsor, officers, and directors failed to make proper disclosures in the proxy statement.12 And, had proper disclosures been made, the plaintiff-shareholders would have exercised their redemption rights.13

As expected, the sponsors, officers, and directors brought a motion to dismiss and argued that the deferential business judgment rule standard of review applied. In a recent ruling, the Court of Chancery rejected the defendants’ argument and applied the more plaintiff-friendly “entire fairness” standard—which shifts the burden of proof to the defendants to show that the complained-of transaction was entirely fair to the plaintiff-shareholders.14 The case, which is still pending, is being closely monitored.

Kwame Amo suggests that breach of fiduciary duties may play a growing role in SPAC-related litigation, and it shows that SPAC-related litigation may be a driving force for changes in fiduciary duty law.

Other claims

Numerous other legal issues have emerged around SPACs. These include claims made under the Securities Act of 1933,15 various common law claims, and numerous SEC actions against SPACs. But we anticipate that the leading edge of SPAC litigation will be claims under the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 and breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims.

Conclusion

It’s hard to determine whether SPACs are a flash-in-the-pan trend on Wall Street or they are here to stay. But one thing is certain: There is a significant amount of SPAC-related litigation and more is expected to arise from current and future transactions. As such, understanding SPACs and the constant legal developments that surround them is paramount for any attorney who practices in this space.

NOTES

2 See the Securities Enforcement Remedies and Penny Stock Reform Act of 1990, Public Law 101-429, available

here.

5 See 15 U.S.C. §78 j and n; see also 17 C.F.R. 240.10b-5 and 240.14a-9 (which are the SEC equivalents to Sections 10(b) and 14(a)).

6 See, e.g., Wheby v. Greenland Acquisition Corp., No. 1:19-cv-01758-MN (D. Del.), ECF Nos. 1, 4.

7 See generally In re Heckmann Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 1:10-cv-000378 (D. Del).

8 See generally Welch v. Meaux, No. CV 19-1260 (W.D. La.).

9 See generally id., ECF No. 1 (9/26/2019).

10 See generally, Kwame Amo v. MultiPlan Corp, et al., Consl. C.A. No. 2021-0300-LWW (Del. Ch.).

11 See generally, Id., (Filed 3/25/2021).

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 Id. (Decided 1/3/2022).

15 Codified as 15 U.S.C. §§77a-77mm (1934).

BRYCE RIDDLE is an associate at Bassford Remele, P.A. Mr. Riddle focuses his practice on business litigation, with an emphasis in complex commercial disputes, employment litigation, and class actions.

KYLE WILLEMSis a shareholder with the law firm Bassford Remele, P.A. Mr. Willems is a business litigation attorney who handles various types of finance-related litigation, including shareholder disputes and directors and officers liability.