A lawyer’s introduction to the exploding field of AI and large language models

By Damien Riehl

“The development of AI is as fundamental as the creation of the microprocessor, the personal computer, the internet, and the mobile phone.” — Bill Gates

The legal profession has long been characterized by daunting hours, high-stress environments, and difficulty in balancing personal and professional lives. Lawyers are well aware of the sacrifice, intellect, and work ethic required to serve clients in this demanding field. What if lawyers could maintain (or increase) revenues while reducing workloads and work hours? What if this same solution could also potentially improve access to justice? Could we navigate the potential benefits and pitfalls? This may be a pipe dream. Or it may be here.

The ascendence of advanced large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and ChatGPT have sparked conversations about the future of the legal profession and how these AI-driven systems might help remedy some of the profession’s less-favorable aspects. Recent, exponential leaps in LLMs have presented both opportunities and challenges that have the capacity to reshape the legal landscape, making the law more accessible and affordable. This article will examine the potential of LLMs like GPT, and how, if approached thoughtfully and ethically, these tools might contribute to a more balanced, efficient, and fulfilling legal career while also improving our society and justice system.

What are large language models?

LLMs like GPT (and PaLM and Dolly) are advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems capable of understanding and generating human-like text. Most people came to know LLMs through ChatGPT, which was released in November 2022, but LLMs’ current technology has its roots in 2017, when a new process enabled exponential leaps in computational linguistic abilities.

LLMs ingest vast amounts of data from the internet, including judicial opinions, cases, statutes, and regulations. The LLMs also ingest law firm websites and blogs, which provide helpful legal information under various states’ laws. LLMs read and incorporate all this text, creating a mathematical data model of ideas and concepts.

They then use all this information to predict the most statistically likely next word, sentence, or paragraph in a given context—representing ideas in a high-dimensional vector space. What is that? Visualize the world’s three-dimensional space. Now try to visualize a fourth dimension. Able to do that? Well now, try to visualize an LLM’s 12,000-plus dimensions. An LLM places words, sentences, phrases, and paragraphs in points among this 12,000-dimensional vector space.

In that 12,000-dimensional space:

- “Force Majeure” is close to “Act of God.”

- “Motion to Dismiss” is close to “Demurrer” (in California).

- “New York Supreme Court” is close to “Trial Court” (remember, New York’s “Supreme Court” is the lowest-level court).

- “Ruth Bader Ginsburg” is close to “Antonin Scalia.”

- “Bob Dylan” is close to “Neil Young” and “Paul Simon.”

In LLMs, closely related terms linguistically are also nearby mathematically (because those terms are in close proximity in the “statistically likely” sense). For example, the blank in the sentence “The hurricane triggered the <BLANK> clause” could be filled with either “Force Majeure” or “Act of God.” They’re both statistically likely. So in vector space, they’re near each other.

The result: LLMs are able to respond to prompts by generating coherent and contextually relevant responses. As LLMs become more sophisticated, and as ingested legal sources become even more comprehensive, LLMs’ potential applications in the legal field will likely expand—allowing them to excel at tasks of increasing complexity.

Why do LLMs matter to the law?

Law’s foundation is built upon words. We as lawyers craft those words to build the framework governing our society. And it turns out that LLMs like GPT are designed to excel at understanding and generating words. The number of GPT-3’s trainable parameters? 175 billion. And GPT-4 is rumored to far exceed that.

This massively eclipses the number of words that any human could ever read, understand, and remember over a lifetime. The size of GPT-3’s vocabulary is approximately 14 million words in 46 languages.1 GPT-4’s size is presumably larger. Bluntly, this dataset is unimaginably massive. As such, its performance at language tasks is currently at the postgraduate level.

LLMs’ extensive knowledge base, combined with advanced analytical capabilities, positions these models as potentially transformative to the practice of law. One might consider an LLM like GPT to be akin to your highly knowledgeable and well-read colleague, but with superhuman writing speed. The vast quantity of legal texts and precedents that LLMs have absorbed can permit the model to provide insights and legal texts with remarkable proficiency. These models can improve (and are already improving) the speed and accuracy of legal work.

Within the legal industry, LLMs could outperform many human lawyers in various tasks (e.g., summarization and drafting), often at a drastically reduced cost. This provides lawyers and law firms with the potential to become more efficient, giving their clients faster, more accurate services. And integrating LLMs into legal workflows could free up valuable time, allowing lawyers to focus on high-level strategic thinking and complex problem-solving.

How good are the most recent LLMs? In March 2023, a team that included U. of Chicago – Kent professor Dan Katz and his partner Michael Bommarito used GPT-4, which powers the most advanced version of ChatGPT, on a simulated multistate bar exam, and GPT-4 outperformed 90 percent of humans.

This is a significant leap from GPT 3.5, which only three months earlier (December 2022) scored in the bottom 10 percent. It’s remarkable: In three months, machines went from “bottom 10 percent” to “top 10 percent” of their human-lawyer competitors.

This astonishing improvement within a three-month timeframe underscores the LLM technologies’ increasing prominence in the legal sector. The whirlwind speed of their exponential advancements invites contemplation about the evolving nature of the legal profession. As AI continues advancing rapidly, how will it redefine the roles of lawyers and other legal professionals?

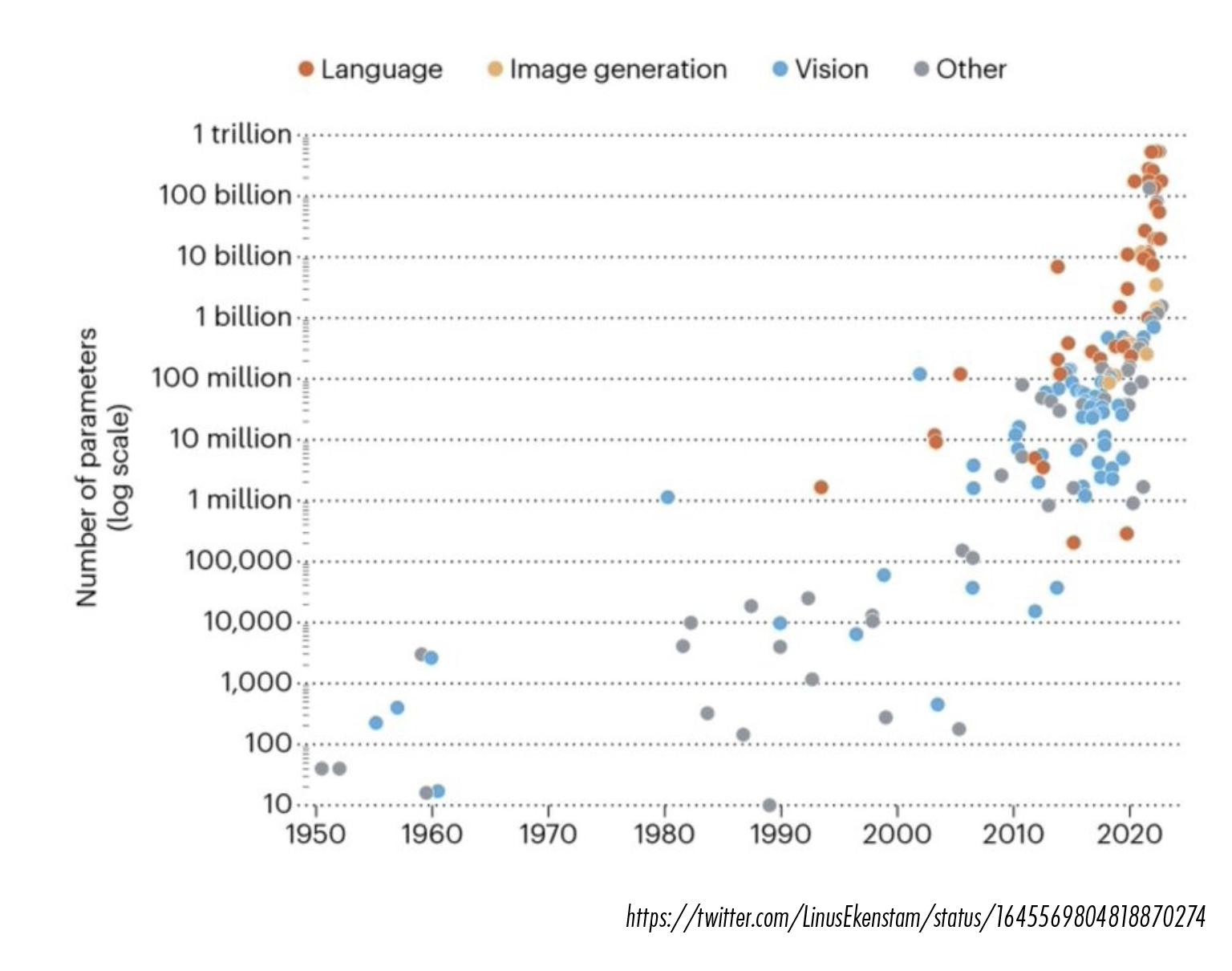

To give a sense of acceleration, below are graphs demonstrating the progress on various metrics — all related to LLMs’ number of parameters, which enhance its ability to perform natural-language (e.g., English) tasks and reasoning:

Notably, the scale of the vertical axis is not linear; it is logarithmic—each horizontal line is 10x the line below it. This type of acceleration on a linear scale would be impressive; seeing this exponential acceleration on a logarithmic scale is mind-boggling. This technology is moving very, very quickly.

Notably, the scale of the vertical axis is not linear; it is logarithmic—each horizontal line is 10x the line below it. This type of acceleration on a linear scale would be impressive; seeing this exponential acceleration on a logarithmic scale is mind-boggling. This technology is moving very, very quickly.

One might argue that even if GPT beat 90 percent of humans on the bar exam, legal practice is far different. And of course that’s true. But how many legal tasks—the kind for which lawyers bill clients every day—are easier than the bar exam?

While the bar exam doesn’t represent all, or even most, aspects of legal practice, how many of lawyers’ daily legal tasks involve reading, writing, and analyzing information? And how quickly can you ingest legal writings and synthesize those writings into text? Faster than LLMs? Better than LLMs?

Today, LLMs can perform many of these tasks faster and perhaps more accurately than many human lawyers, especially when performance is compared to the first drafts from junior lawyers (such as first-year associates). Today’s LLMs perform at a post-graduate level. Tomorrow’s LLMs will be better. (See exponential growth curve, above.)

As LLMs become increasingly sophisticated and capable of handling complex legal tasks, that performance increase will also raise questions about the role of traditional legal education. Do today’s law schools prepare lawyers for practice in an LLM world? If LLMs perform better than junior associates and this results in fewer junior associate hires, how much will law school enrollments drop? What prospective student will want to pay $150,000-plus for a legal education that won’t get them jobs?

Everyone should consider these questions: How much could a “trusted LLM associate” improve lawyers’ work quality and increase productivity? How can we prepare our law students for the jobs they’ll have upon graduation? And can the adoption of LLMs spur new developments in legal technology, enabling the creation of novel tools and services to better serve clients?

Unquestionably, LLMs’ costs are far, far lower than employing human lawyers: A GPT-4 prompt costs a fraction of a penny. And the newest open-source LLM models (e.g., Dolly 2) are free. How much could this increased affordability increase legal demand, as more individuals and businesses seek advice and assistance? Previously underserved markets may be able to gain access to legal services, further expanding the reach of the legal profession.

How well do LLMs perform on legal tasks?

Personal experience and anecdotal evidence indicate that LLMs’ current state provides impressive output in various legal tasks. Specifically, they provide extraordinary results on the following:

- Drafting counterarguments.

- Exploring client fact inquiries (e.g., “How did you lose money?”).

- Ideating voir dire questions (and rating responses).

- Summarizing statutes.

- Calculating works’ copyright expiration.

- Drafting privacy playbooks.

- Drafting motions to dismiss.

- Responding to cease-and-desist letters.

- Crafting decision trees.

- Creating chronologies.

- Drafting contracts.

- Extracting key elements from depositions.

While the output generated by LLMs might not be acceptable as a final draft, it usually surpasses the quality of work produced by junior lawyers (and even some senior lawyers).

Before you think “I don’t trust it, and I don’t want to edit a machine,” ask yourself this: When was the last time you accepted an associate’s draft without edits? How about your similarly experienced peers? Everyone needs an editor. And with LLMs, more experienced lawyers can begin editing output after waiting mere seconds, not days.

LLMs have increased performance in other language-based tasks—as demonstrated by related fields. For example, Michael Bommarito and Dan Katz founded two software companies, one before the advent of GPT and one afterward. In the first company, they hired 20 employees, and it took 24 months to build a product that they then sold, exiting the company. For the second company, they used a GPT-powered coding tool called GitHub Copilot that Michael Bommarito estimates allowed him to improve coding speed and accuracy by between 10x and 100x. So the second company didn’t take 24 months to build; it became operational in just three months. And given Mike’s 10x performance increase, they didn’t have to hire 20 employees; they’ve hired none. The job market for coders decreased by 20. Those jobs no longer exist.

For coding, LLMs are transformative. Because LLMs are great at producing code. And LLMs are also great at producing words. Law is words.

A transformed business of law?

Because lawyers spend much of their time reading, writing, and analyzing words, and because words are the currency of the LLM realm, the potential for LLMs to improve efficiency in legal tasks is substantial.

While it’s difficult to quantify the exact performance increase that LLMs can provide to lawyers, the potential for significant improvements in efficiency is evident. The impact of LLMs on the legal industry could be akin to the effect of steam engines on the Industrial Revolution. Just as steam engines revolutionized manufacturing and transportation, drastically increasing productivity, LLMs could similarly reshape legal work by streamlining research and analysis. Lawyers could be enabled to tackle more complex cases and serve a broader range of clients, while also reducing overall costs.

Of course, the integration of LLMs into the legal industry presents new business opportunities and challenges. The classic Cravath law firm model, pioneered over 100 years ago by the prestigious Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP, takes the shape of a pyramid: A large base of junior associates supports a smaller group of partners. Associates work long hours, while partners supervise and generate new business. That model has prevailed for over a century, but it might be in need of an update.

With LLMs’ efficiency gains, leveraging associates’ time under the Cravath model could become difficult or impossible: The technology may drastically reduce the time needed for legal research and document review. Tasks that took hours can now take seconds. How will partners leverage associates’ time in a world where all lawyers, including associates, will spend far less time? Where is the leverage? Our industry may need to modify organizational structures and business models to better incorporate LLMs’ unique advantages.

Let’s take a common example: A corporate in-house lawyer needs to answer a legal question. In the age of LLMs, she is faced with two options:

OPTION ONE: Human answer

Client lawyer calls law firm partner.

Partner assigns associate.

Turnaround: Two days

Fee: $2,000? ($400/hr at 5 hours).

OPTION TWO: Ask an LLM

Client lawyer asks LLM (e.g., GPT-4)

Turnaround: 20 seconds

Fee: $0.002 ($20/month for queries)

CLIENT PERCEPTION OF ACCURACY:

Human Lawyer: Perhaps 95 percent?

Large Language Model: Perhaps 90 percent (like the bar exam)?

Will clients believe that a human lawyer’s added value is worth the massively increased time and cost? The traditional model of in-house counsel seeking legal advice from law firm partners, who then assign tasks to associates charging hourly rates, may well be disrupted.

The worst part: That Option One lawyer won’t know why their phone didn’t ring. The client simply didn’t need them.

Hourly fees vs. flat fees

The efficiency and cost-effectiveness of LLMs could well nudge the legal industry away from hourly billing and toward flat fees. How will firms adapt where an hours-long legal task is reduced to seconds? Perhaps you can charge a flat fee—similar to what the lawyer would have earned after a few hours—reflecting not the hours worked but instead the conveyed value.

Value-based pricing models can consider factors like matter complexity, required expertise, and the clients’ potential outcome. By focusing on the value delivered, firms can justify higher fees while maintaining their competitive edge. This shift could also lead to greater billing transparency and improved client satisfaction: Clients understand costs upfront, and lawyers have incentive to increase the efficiencies afforded by LLMs. Combining value-based pricing with LLM-driven efficiency gains could help law firms adapt to the changing dynamics of the legal industry while continuing to provide high-quality services to their clients.

One matter, one lawyer?

The integration of LLMs into legal practice could also shift the focus from a leverage model, where multiple associates work on a single matter, to a model in which one lawyer (perhaps a senior associate or above) works on a single matter. Assisted by an LLM, that senior associate might be able to increase productivity by 10x. And because the senior associate has enough experience to give the LLM the perfect prompts, their performance can exceed that of junior associates, who lack the subject-matter knowledge to prompt effectively.

In this new world, what will be the job prospects for junior associates? And if associates’ job prospects decline, what does that mean for law school enrollment? Again, who will want to spend $150,000-plus on a legal education to enter a legal market that doesn’t need first-year associates?

And if associates become rarer: How will junior associates grow into senior associates? How does one get experience absent the traditional routes to gaining experience?

Increased access to justice?

If we’re moving toward “one matter, one lawyer,” perhaps those junior associates can cut their teeth by hanging out a shingle and serving clients who might not be able to afford a lawyer in today’s system. And because LLMs will make them more efficient, those junior lawyers could serve many more clients.

This approach could expand opportunities for junior lawyers potentially displaced by a “one matter, one lawyer” system. By serving more clients, those junior lawyers could gain valuable experience while simultaneously addressing the justice gap that exists for many individuals and small businesses. Armed with LLMs, junior lawyers could efficiently provide cost-effective legal services to clients who were previously priced out of the market.

By reducing legal costs and increasing efficiency, LLMs have the potential to improve access to justice for individuals and organizations. Could this shift level the playing field for those who were previously unable to afford legal representation?

Specifically legal LLMs

The current LLMs are trained on the entire internet, including low-quality sources such as social media. And it still beat 90 percent of humans in the bar exam.

Now, what if an LLM were trained on high-quality legal documents—such as judicial opinions, statutes, and regulations? How much better would this type of “law foundation model” fare on legal tasks? How much better would its legal reasoning be for items like the Rule of Perpetuities? Or more-complex legal tasks?

Researchers from NYU, MIT, Chicago, and Stanford are currently exploring the potential of such specialized large-language legal models. By building a foundational model solely on legal text, the researchers believe that the legal LLM might know the law “natively.” And as such, the legal LLM might be even more capable of completing tasks of ever-increasing complexity.

By focusing on authoritative and reliable sources of legal information, this specialized legal LLM would likely demonstrate a deeper understanding of the intricacies of legal reasoning and the nuances of various doctrines and complex concepts. This enhanced knowledge base might enable the legal LLM to tackle a broader range of tasks with greater accuracy and efficiency, providing even more value to lawyers and clients alike.

With a “law first” legal LLM, the legal industry could witness a further transformation in the way it approaches and resolves legal issues. This new model could be capable of not only handling tasks of increasing complexity, but also of contributing to the evolution of legal practice. The LLM could handle increasingly complex research and analysis, while human lawyers would be permitted to focus more on strategic decision-making, advocacy, and negotiation.

This would move our industry from “Lawyers vs. Robots” to “Lawyers with Robots.” (Centaurs!) Symbiotic relationships between legal professionals and advanced LLMs could lead to the emergence of a more agile and adaptive legal ecosystem, capable of addressing our increasingly diverse clients and our increasingly regulated corporate clients.

Implications for courts

As LLMs become more widely used by lawyers and clients alike, courts may face new challenges that require new solutions. Today, courts are often overwhelmed by the volume of cases. Current court backlogs are substantial. With litigants and their lawyers aided by LLMs, might those backlogs get longer?

To address the current backlog, which may be exacerbated by the potential rise in caseload, courts might choose to employ AI-powered tools. This would be a modern approach addressing access to justice, while ensuring fairness. Judges and courts could use these tools to help prioritize cases based on urgency or complexity, automatically generate first-draft procedural orders, and identify issues that can be quickly resolved. By streamlining initial litigation, courts could then allocate resources to focus on cases that require more judicial attention.

Other tools could help in the judicial decision-making process. For example, courts could use AI tools to compare the parties’ briefs, more quickly demonstrating “apples to apples” arguments, elucidating logical gaps, and expediting judicial drafting. These tools could not only expedite the decision-making process, but also better ensure that judicial decisions are consistent with established legal principles.

Of course, any technical assistance must be guided by the bright lights of human oversight. Judges and their staff must always guide those processes. Additionally, one could imagine platforms that help pro se litigants navigate the legal system more effectively, reducing the burden on court staff and judges. (Of course, the widespread use of AI tools could potentially increase caseloads by increasing the volume and viability of pro se litigation, but that is a subject for another article.) These platforms could also be designed to encourage early settlement or resolution, further easing judicial strain.

By embracing AI-driven solutions to manage and decide cases more efficiently, the judiciary can adapt to the changing landscape of litigation and continue to uphold the principles of justice and fairness.

Conclusion

LLMs like GPT-4 have given the legal profession the potential to positively transform society. But this is, of course, just one possible future. It might not happen. Our profession, our clients, and our courts could shrug their collective shoulders and go back to business as usual. We could continue practicing law with the same business model and substantive habits that we’ve used—and the access-to-justice crisis that we’ve endured—for many decades.

But this time, it might really be different. As LLMs become more sophisticated and specialized, they could help streamline legal processes, reduce costs, and improve access to justice. While the integration of LLMs into the legal profession raises many questions about the future roles of lawyers and the business of law, it could benefit lawyers individually and collectively, as well as improving society more broadly.

The rise of LLMs presents an opportunity for the legal profession to address long-standing issues, such as the access-to-justice gap and the need to streamline dispute-resolution mechanisms. By leveraging LLMs, lawyers can provide more affordable and accessible legal services to a broader range of clients, helping to bridge the justice gap and promote greater equity within the legal system.

Lawyers, technologists, and policymakers should work together to address ethical, regulatory, and practical challenges. But LLMs like GPT-4 have the potential to improve the legal profession and redefine the way legal services are delivered. We can improve how the law serves society. By embracing change and proactively adapting to the evolving legal landscape, the legal industry can potentially lead the way to a more efficient, accessible, and just legal system.

DAMIEN RIEHL is a technology lawyer with experience in complex litigation, digital forensics, and software development. Coding since 1985, he clerked for the chief judges of state and federal courts, litigated with Robins Kaplan for over a decade, led cybersecurity and forensics investigations, and uses AI to build legal software. Damien co-chairs the MSBA working group on AI and the Unauthorized Practice of Law (UPL).