By Robert M. Schuneman

What do you think about ______?” is a common question. We ask this question because we recognize that what people think about a particular subject varies based on numerous factors. On many topics, most of us would stipulate to a wide variety of opinions and thoughts.

Suppose we extend that understanding to a different question: “How do you think?” We don’t know how—that is, by what specific processes—our brains think, react, or otherwise process information. Theories abound to explain all manner of neurological functioning, but ultimately, we have few definitive answers about how our brains work. Could there be a diversity of processing and function similar to the observed variety of opinions and thoughts?

Many researchers tacitly acknowledge the lack of understanding of how our brains work by using the black box model, which is defined at Oxfordreference.com as “a model of information processing in which an individual is considered to be a black box into which information flows from the environment. The information is processed in various ways inside the box until it is expressed as observable behavior (the output). Researchers using this model focus mainly on what goes into the box (the information or stimuli) and the behavioral output. Nothing of the structure of the box is known beyond what can be deduced from the behavior.”1

Within this context, medical and psychological fields identify specific behavioral patterns as disorders or diseases, presupposing that the behavior patterns per se represent pathological deviations from the norm. But what if this model is flawed? What if the observed behavioral patterns aren’t deviations but instead are rooted in the diversity inherent in our DNA?2

These seminal questions became the starting point of neurodiversity. Haley Moss, an attorney and neurodiversity movement advocate, defines neurodiversity as an understanding that “we all have different brains. We all think differently, and no two people experience the world in the exact same way. No one brain is better than another.”3 In the words of another activist, John Elder Robison, “neurodiversity is the idea that neurological differences like autism and ADHD are the result of normal, natural variation in the human genome.”4 Judy Singer, the person credited with coining the term neurodiversity, observes, “We are ALL neurodiverse because no two humans on the planet are exactly alike; our planet has a neurodiverse population.”5

Approximating “normal” cognitive information processing

Evaluating whether behavior conforms to a society’s expectations—to a norm—is a straightforward exercise that lawyers regularly undertake, particularly when the expectations are codified as law. But what is a behavior if not an observable result of brain activities and processes that cannot be directly observed? To conclude that the same or similar behaviors result from the exact same brain processes is faulty. Consider, for example, two people who arrive at the courthouse simultaneously. It would be improper to conclude or even theorize that, since they both arrived at the same place contemporaneously, they took the same route or even the same mode of transportation. It would be equally fallacious to conclude that each time the same person goes to the courthouse, they use the same route and method of transportation.

Consequently, while we can evaluate the conformity of behavior to a norm, we cannot assess the underlying brain processes similarly. Observed behavior becomes a proxy representing our assumptions about the underlying brain processes. Without a better method of determining the cause of the deviant behavior, our behavioral assessment prevails. The evaluation of an individual’s behavior becomes associated with—and perhaps inseparable from—the individual. As Damian E.M. Milton has written, “To be defined as abnormal is potentially to be seen as ‘pathological’ in some way and to be socially stigmatized, shunned, and sanctioned.”6

Neurodiversity is a DEI issue

The term “neurodiversity” is political rather than scientific. In her seminal work on the subject, sociologist Judy Singer wrote, “For me, the key significance of the ‘Autistic Spectrum’ lies in its call for and anticipation of a politics of Neurological Diversity, or ‘Neurodiversity.’ The ‘Neurologically Different’ represent a new addition to the familiar political categories of class/gender/race.”7

Singer’s “original conception of Neurodiversity was as an addition to the categories of intersectionality[,] thus an analytical lens for examining social issues such as inequity and discrimination; an umbrella term as a possible name for a civil rights movement for the neurological minorities beginning to coalesce around the pioneering work of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Movement.”8 Singer’s vision of an umbrella concept under which multiple neurological minorities could coalesce reflects today’s neurodiversity movement. As she wrote, “The Neurodiversity Movement refers to the disability rights movement aimed at full inclusion for all neurodivergent9 people.”10

From its roots in autism self-advocacy, the neurodiversity movement umbrella now “encompasses neurocognitive differences such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, Tourette’s syndrome, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, intellectual disability, and schizophrenia as well as ‘normal’ neurocognitive functioning.”11

The neurodiversity movement rallies around its motto, “Nothing about us without us!” while fighting to change conversations about neurodiversity.12 Movement activists decry the status quo in which “[n]eurodivergent people are routinely excluded from key conversations that impact their lives. In high-level policy discussions, social justice and disability rights activism, autism [and other conditions] awareness campaigns, contemporary ‘mainstream’ media discourse, and everyday conversations, autistics and other neurodivergent people are often ‘erased, silenced, [and] derailed.’”13 One of the movement’s animating principles seems both obvious and intuitive: “Disabled people know better than non-disabled people what it is like to be disabled. Disabled people who do activism or advocacy tend to have a keen grasp of issues affecting them and people like them.”14 Yet neurodivergent people are routinely left out of meaningful policy discussions.

Neurodivergence and identity

The freedom to define and express one’s own identity is highly valued and protected, at least on an individual basis, as long as one lives within the framework of generally accepted behavioral norms. Problems commonly arise when aspects of a person’s identity or the expressions of those aspects run counter to those norms. American society typically views neurodivergent conditions as medical or psychiatric anomalies, things to be “treated” and “cured” if possible, or “managed” when a cure is not available. Within the neurodiversity movement, however, and particularly among autism activists, many advocates embrace their neurodiversity as part of their identity. Consider this observation from Jim Sinclair, an early autism activist: “Autism is a way of being. It is pervasive; it colors every experience, every sensation, perception, thought, emotion, and encounter, every aspect of existence. It is not possible to separate the autism from the person—and if it were possible, the person you’d have left would not be the same person you started with.”15

There are two general ways to talk about someone who has a health condition. As the attorney and advocate Haley Moss has written, “Person-first language is intended to keep the human at the center of the conversation and is intended to be respectful of an individual. Identity-first uses the disability as a defining characteristic, similar to race, religion, sex, or gender. Person-first language sounds like ‘Haley has autism’ or ‘Haley is a woman with autism’ and identity-first language sounds like ‘Haley is autistic.”16

A person may have a preference for how they want to be described or referred. The best practice for lawyers is to listen when someone tells them their preference and follow their advice. This is consistent with the emerging practice of communicating using one another’s preferred personal pronouns

What lawyers need to know about neurodiversity

• Neurodiversity is a new term reflecting an old reality—that we’re all different and unique. Yet neurodiversity transcends that common understanding by seeking to value not only the differences but also their source. Complicating factors include the value society places on the differences, the accommodations it is willing to make to include people with differences, and its willingness to recognize their inherent dignity and worth.

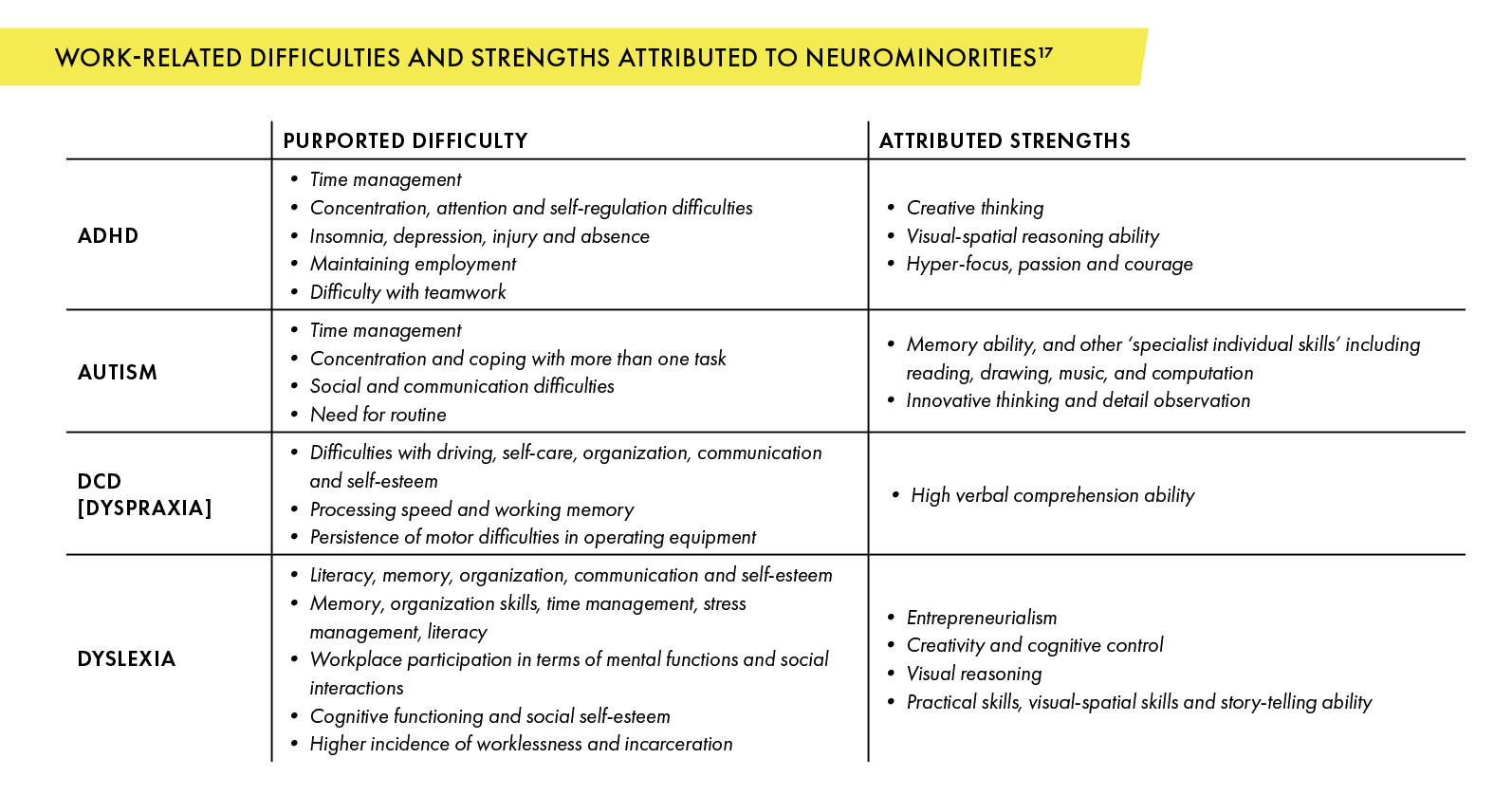

• The neurodiversity movement challenges the conventional “medical model of disability.” The movement seeks recognition that specific neurological conditions have occurred throughout history and may not result from “disease” or “defect” but instead from the diversity inherent in the human genome. Furthermore, while these conditions are typically associated with their deficits, they can also confer benefits upon those who have them. (See table.) Not all neurodivergent people experience the attributed strengths to the same degree, if at all.

Work-related difficulties and strengths attributed to neurominorities17

• Neurodivergent people experience implicit bias, stigma, and preconceptions based on stereotypes. Many of the barriers to inclusion encountered by neurodivergent people result from implicit bias, stigma, and preconceived notions of what “a person with x condition” can and cannot do. These same barriers encourage neurodivergent people to “act the part” of a “normal” person to the extent they are able.

Perhaps we’re asking the wrong question when we ask “how should we deal with” neurodiversity and related issues. A better question might be, “how can we better support our neurodivergent clients and colleagues?” As Haley Moss observed, “[W]e ultimately are a service profession providing access to justice and need to be sure to be equitable and accessible to those who are often denied access to justice—neurodivergent people are often silenced and unheard in the legal system.”18 I’d add an observation that, for most people, interacting with lawyers and the legal system is stressful, which can exacerbate many neurological conditions.

Within a person-centered service model, a lawyer goes beyond a mere presumption of the client’s competence to develop an understanding of the context within which the client’s legal issue arose. This context can be, and often is, best understood by recognizing a client’s neurodivergence and adapting to it. For example, an autistic client may be quite capable of managing a list of three tasks related to their case, but a list with 20 items might be overwhelming. This limitation doesn’t affect the client’s competence, yet it would affect the client’s ability to participate in their case within the lawyer’s deadlines. It may be more work for the lawyer to break down the more extensive list into smaller chunks. Still, increased client satisfaction and participation should justify the extra effort both for our clients and ourselves.

Lawyers are people too

Many neurodivergent legal professionals, including lawyers, excel at their jobs, although some may hide their neurodivergence. As a profession, we all benefit when each member is encouraged to do their best work and welcomed for the unique set of skills, experience, and perspective they bring.

In addition, countless legal professionals have wrestled—and continue to grapple—with mental illnesses or addictions. “Depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are three common characteristics that exist in every law firm,” noted writer Terry Carter in an ABA Journal article. “The reality is that firms are dealing with this whether it’s in the open or not.”19

Maybe instead of trying to “deal with” these issues as though they are problems with potential solutions, we should instead ask, “how can we create an environment where everyone can do their best work?” Imagine a workplace organized around supporting and encouraging everyone to do their best work.

That would be a fantastic place to work. Let’s build it.

ROBERT M. SCHUNEMAN practices civil litigation and business law in Apple Valley. He brings substantial practical experience as a business executive and educator to his practice. Before joining the Tentinger Law Firm in February 2022, he served as outreach coordinator for Minnesota Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers.

Notes

1 Oxford Reference, Black Box Model, available at https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095509539.

2 See Thomas Armstrong, The Myth of the Normal Brain: Embracing Neurodiversity, AMA J. Ethics, 17 (4):348-352 (April 2015).

3 Haley Moss, Great Minds Think Differently: Neurodiversity for Lawyers and Other Professionals, ABA Senior Lawyers Division, (2021), pp. xvii.

4 John Elder Robison, What is Neurodiversity?, Psychology Today (blog) (10/7/2013), available at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/my-life-aspergers/201310/what-is-neurodiversity.

5 Judy Singer, What is Neurodiversity?, Reflections on Neurodiversity: Afterthoughts, Ideas, Polemics, Not always serious (blog), available at https://neurodiversity2.blogspot.com/p/what.html.

6 Damian E. M. Milton, On the Ontological Status of Autism: the ‘Double Empthy Problem’, Disability & Society, 27 (6):883-887, (2012).

7 Judy Singer, Neurodiversity: The Birth of an Idea, (2017) (ebook), loc. 90 (quoting a book chapter she authored in Disability Discourse, Open University Press, UK (1998), p. 64.)

8 Judy Singer, What is Neurodiversity?, Reflections on Neurodiversity: Afterthoughts, Ideas, Polemics, Not always serious (blog), available at https://neurodiversity2.blogspot.com/p/what.html.

9 “Neurodivergent individuals are those whose brain functions differ from those who are neurologically typical, or neurotypical.” Jessica M. F. Hughes, Increasing Neurodiversity in Disability and Social Justice Advocacy Groups, Autism Self Advocacy Network, (2016), p. 3.

10 Supra note 8.

11 Id. Lists of included conditions vary by source. See Mirriam Moeller, et al., Neurodiversity can be a workplace strength, if we make room for it, The Conversation (9/8/2021), available at https://theconversation.com/neurodiversity-can-be-a-workplace-strength-if-we-make-room-for-it-164859 (listing “[t]he most common are: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Dyslexia, Dyspraxia, Dyscalculia, and Tourette syndrome). See also Judy Singer, What is Neurodiversity?, Reflections on Neurodiversity: Afterthoughts, Ideas, Polemics, Not always serious (blog), available at https://neurodiversity2.blogspot.com/p/what.html (containing a graphic of The Neurodiversity Movement depicted as a large umbrella under which are smaller umbrellas labeled autism, ADHD, DYS+ [representing dyslexia, dyspraxia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia], tics [a class of disorders including Tourette’s syndrome, essential tremors, and related neurological movement disorders], LD [learning disabilities], speech, and “other?”).

12 Jessica M. F. Hughes, Increasing Neurodiversity in Disability and Social Justice Advocacy Groups, (2016), p. 4.

13 Id. at p. 3. (quoting A. Hillary, Erased, silenced, derailed, Yes That Too (blog) (3/5/2013), available at http://yesthattoo.blogspot.com/2013/03/erased-silenced-derailed.html ).

14 Id. at 4. (quoting Lydia Brown, Autistic Representation Crisis in Massachusetts (but dying of not surprise), Autistic Hoya (blog) (2/3/2016), available at https://www.autistichoya.com/2016/02/autistic-representation-crisis-massachusetts.html ).

15 Jim Sinclair, Don’t Mourn for Us, Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies, vol. 1, no. 1 (10/3/2012).

16 Moss, pp. 23-24.

17 Nancy Doyle, Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults, British Medical Bulletin, 2020, 135:108-125, p. 116 (internal references omitted; each element in the table is supported by one or more references).

18 Moss, p. 25.

19 Terry Carter, The biggest hurdle for lawyers with disabilities: preconceptions, ABA Journal (6/1/2015), available at https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/the_biggest_hurdle_for_lawyers_with_disabilities_preconceptions