What to expect as courts work to deliver justice through the rest of the pandemic

By Kristi J. Paulson

When I opened my eyes on New Year’s Day 2020, I looked forward to a year of work that would revolve around trials. Two cases that had been languishing were finally scheduled for trial, and my mediation practice calendar was already filled with dates running into the summer and fall.

When I opened my eyes on New Year’s Day 2020, I looked forward to a year of work that would revolve around trials. Two cases that had been languishing were finally scheduled for trial, and my mediation practice calendar was already filled with dates running into the summer and fall.

And then—well, you know. Beginning in March, the coronavirus closed courthouse doors across the nation. Jury trials, the backbone of the American system of justice, were stopped or suspended by court order.

After months of closures, courts necessarily began to reopen. Slowly. Technologies such as Zoom had been adopted to allow pleas, sentencings, and motions to go forward. But the jury trial—since its inception, an in-person process—challenged the court system and threatened to stall justice. Courts faced the unprecedented challenge of rethinking every stage of the process, from how voir dire is used to select the jury all the way through the delivery and rendering of the verdict by that same jury.

Courts nationwide suddenly were faced with the tricky task of redesigning the jury trial to balance the health of the jurors—compelled by law to serve—with the jury trial rights of defendants, many of whom had seen their cases stall for months. Courts struggled to address defendants’ rights to speedy and public trials while also treating fairly the involvement of a variety of outside individuals.

September marked the first civil jury trials to take place in Minnesota’s court system since the start of the pandemic; two trials proceeded in Hennepin County on the same floor on the same day. Those two cases were tried to verdict and demonstrated that, with proper care and precautions, justice could go forward.

Though an autumn surge in covid infections in Minnesota and around the Midwest once again put in-person proceedings on hiatus, we can expect that jury trials will be resuming in Minnesota courts under pandemic precautions and that the system will continue to operate in that mode for the foreseeable future as the long process of inoculating the American public proceeds in 2021.

So what will courtrooms look like as we return to jury trials in the not-too-distant future?

What can we expect our courthouses to look like?

Courts across the country have recognized the need to implement communicable disease safety protocols. This is an expensive and time-consuming process for the courts, many of which were already facing funding and staffing challenges.

Going forward we can expect to keep seeing what has become known as the “covid questionnaire” to screen for possible exposure. Individuals will be subject to temperature checks. Without question, masks will remain mandatory. There will be hand-sanitizing stations throughout the courthouses. Many jurisdictions have reported increasing the size of cleaning crews for use during the jury process.

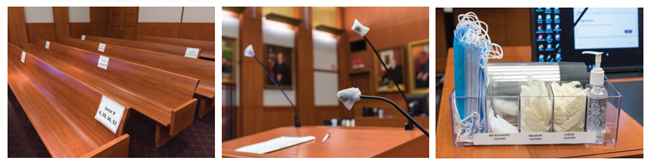

In this time of “six feet apart,” physical logistics will pose a whole new set of headaches: how many people a jury box can safely hold; how far apart witnesses need to be; where lawyers and clients can be in relation to the judge. Strategically placed plexiglass will fill courtrooms to provide barriers and shield jurors, witnesses, and court personnel. One or two courtrooms will be identified as jury trial courtrooms. Counsel tables will be equipped with plexiglass barriers to protect attorney and client. Jury trials will be limited. The U.S. District Court in Minnesota has indicated that when jury trials resume, only one jury trial will be conducted at a time until the court is comfortable with the process—and that no more than two trials at one time will be conducted in either Minneapolis or St. Paul.

U.S. District Court Chief Judge John Tunheim’s Minneapolis courtroom has been extensively modified with plexiglass partitions and covid-related supplies and signage. (Stan Waldhauser)

What role will technology play in trials?

Technology isn’t just underwriting more remote participation; courtrooms are seeing an increase in the use of devices to permit communication between counsel and the court. Some courtrooms are being supplied with tablets to enable such communication, and headsets with microphones that allow for private communication are now being integrated into the courtroom scene. Zoom appearances are becoming more the norm than the exception, and courtrooms are being outfitted with monitors and devices to allow jurors and the parties to adequately see and hear witnesses presenting testimony.

What will pre-trial stages look like?

Pretrial hearings and conferences are essential elements to address potential issues that will come up in trial. Generally, these are in-person meetings between the judge, counsel, and parties; for the foreseeable future, most pretrials will be taking place via Zoom instead. And these conferences are likely to become even more important as courts try to minimize evidentiary disputes and bench conferences. Being prepared will prove more important than ever: Advance determinations regarding motions in limine, the marking of exhibits, and agreements as to evidence and witnesses can greatly speed along the trial process.

For the short term, case selections are likely to be carefully considered. There may be a tendency to avoid complex and lengthy cases while covid-19 numbers are surging. Processes such as settlement conferences, alternative dispute resolution, and bench trials will likely see an increase in use by lawyers and judges.

How will we select our juries?

The pandemic presents numerous challenges in picking a jury and conducting voir dire. Traditionally, both of these processes have involved large groups and close gatherings. Prospective jurors are bound to harbor fear and safety concerns that will need to be addressed. The vetting process will have to include questions about their concern for their own individual safety and health and that of family members. No one wants a juror’s mind to be on anything but the trial at hand.

Courts will face the challenge of making sure that jury pools reflect the community and will prove fair to those using them. When certain segments of the community are being told to stay home, there will be questions about whether a trial is truly by one’s peers; to the extent that the groups hardest hit by covid-19—the elderly, minorities, individuals with health issues—begin to opt out of the jury process, the jury pool may be affected.

The importance of jury questionnaires has become evident during the pandemic. More and more judges are now using them to learn basic information as courts try to minimize contact by limiting the number of jurors called. Supplemental medical questionnaires, sealed and available only to the court, ask for private medical information about covid-19-related issues to allow the court to properly protect the health and safety of all involved.

One other notable difference has been the pressure to reduce the size of the jury pools. During the past year Minnesota courts have sought to keep the number of jurors called for voir dire small. There has been pressure to empanel a jury quickly and keep the trial process moving. Similarly, there was pressure to reduce the number of alternates due to potential covid exposure issues. Every alternate juror is one more person to put at risk or pose a risk in the process. In civil cases, attorneys are now being asked to discuss circumstances in which less than unanimous verdicts might be accepted.

Where will we select our juries?

While in-person questioning may be preferable, courts and attorneys are discovering that voir dire questioning of a prospective jury panel can be done online in a virtual setting. Many jurisdictions are going forward with jury selection at an alternate offsite location that provides for better distancing. Empty arenas, college auditoriums, and large libraries have accordingly been pressed into service as places to question prospective jurors. Other jurisdictions are exploring a form of remote voir dire in which prospective jurors may be questioned at home, or in some cases at “Zoom rooms” inside courthouses.

One difference that seems to be emerging in covid time: When a juror is discharged, he or she is sent home, not told to wait around for another case. And there’s no longer coffee in the jury room.

May it please the court: Opening statement and closing arguments

Lawyers love to move around the courtroom, and never more than during opening statements and closing arguments. Judges are now instructing lawyers that they have to remain behind the podium and limit movement. Lawyers pride themselves on connecting with the juries and movement is an essential tool, now restricted. Trial lawyers feel confined.

The social distancing requirements are creating new challenges and logistical issues with the ability of the lawyers to connect with the jurors and for the jurors to see the evidence.

Should we unmask the witnesses?

Masks pose a variety of conundrums. It can be hard to hear someone speaking through a mask. Lawyers cannot see the fleeting smiles, scowls, or smirks that often communicate more than words. Clients can look like bandits; masked lawyers who stand in front of juries asking for money can look like bank robbers.

Witness testimony is routinely taken in open court so that the jury can assess the credibility of the witness and weigh the evidence at trial. The mask requirement has created some barriers to this assessment that most courts are finding cannot be offset. As a result, surrounding an unmasked witness with plexiglass is seemingly common. The attorneys in the recent Hennepin County case indicated that the witnesses did not wear masks but were placed behind plexiglass barriers. Other attorneys trying cases in this era have reported that witnesses wore face shields. Some courts are now mandating clear masks that will be worn by all witnesses.

The importance of being able to see the nonverbal communication of the witness is becoming increasingly evident. Elements like eye contact and the facial expressions and reactions of the witnesses are often as important as the words the witness speaks. In the interest of justice, courts will likely unmask witnesses, but take precautions to ensure the well-being of those witnesses.

What about the mask protocols for everybody else?

Lawyers will continue to be required to wear masks in the courthouse and the courtrooms. The recent developments of items such as clear masks or masks printed to match facial features may mean that these masks are not so noticeable. Some jurisdictions are going so far as to use court-ordered masks so that everyone presents a consistent appearance in the courtroom. One piece of advice, though: Don’t forget to carry a spare mask. You never know when you might need it.

While lawyers may not like masks on jurors, they are likely to remain. And they will frequently make it difficult to gauge reactions and determine who is paying attention. But courts are likely to determine that both parties are equally disadvantaged in this regard and public safety outweighs those concerns.

What about the support systems of people on trial? The presence of friends and family at trial are generally deemed essential to communicate the client/defendant’s humanity to jurors and to provide emotional support to the client or defendant. Distancing restrictions will have a distinct impact on this dynamic, as courts prohibit additional people in or around the courtroom in the interest of public health.

May I publish this exhibit to the jury?

In trial, lawyers often will admit evidence and then ask permission to publish that exhibit to the jury. This allows that piece of evidence to be handed to the jurors and passed through the jury box.

At least for the time being, that isn’t how it’s likely to go. There is continuing concern about the touching of surfaces, including exhibits. Gloves have not factored into this pandemic generally and seem to actually offer a false sense of security. Courts and counsel seem to be addressing this issue by creating additional sets of paper exhibits and limiting the touching of such items.

The fact that the jurors tend to be spread out throughout the courtroom and sometimes between rooms further complicates the use of tools such as foam-board exhibits, flip charts, and white boards. These are effective when the jury is seated so they can all see them but lose the effect when you have to wheel them around. But creativity is all part of being a lawyer and it won’t be long until we will see new methods of communicating information visually to jurors.

Jury, have you reached a verdict?

Deliberation is fundamental to the process of trial by jury. Traditionally, the jurors have been placed in small rooms—and always in person. This arrangement allows them to discuss the evidence, think about the testimony and statements they have heard, share ideas and rationales, and move to a collective decision. These secret, private deliberations often go on for hours or days.

Essential to this process is the safety and well-being of the jurors. Larger spaces will need to be used in order to allow the safe distancing of jurors. Privacy concerns will also need to be factored in. For example, most courtrooms contain communication systems, and privacy will require that they be disabled in spaces that will be used for deliberations. The role of court clerks and deputies will likely change some as we juggle the need to safeguard the jurors and yet meet their needs, permitting them to do their assigned duty and render a verdict.

Masks and sanitizing procedures will need to be strictly enforced. There will need to be standards in place for the handling of exhibits. There may be a need for longer breaks—which, in turn, may increase the deliberation or trial time. Even things as simple as transporting jurors in elevators will need to be factored in—you simply cannot put the entire jury on one elevator, as has been done in the past.

What if someone tests positive during trial?

One of the greatest challenges for courts holding jury trials in the covid-19 era will be what to do in those inevitable instances when someone involved in the trial tests positive. Options such as declaring a mistrial, temporarily adjourning the trial, or continuing with alternates are all options. Courts will have to grapple with safety and health issues such as the question of testing all participants in a given trial.

This is likely to be a developing issue. Courts will no doubt continue to place an emphasis on moving things along quickly in case someone gets sick. But as longer and more complex trials return to the court system, these issues will play more of a role. It is only a matter of time.

Conclusion

At the time of this writing, Minnesotans have experienced over 450,000 cases of covid-19, and more than 6,000 people have died as a result. The Minnesota Judicial Council announced in mid-January that criminal jury trials, which had been scheduled to recommence on February 1, would remain suspended until March 15. But as the Star Tribune noted in its story about the move, “the council increased the exceptions that would allow for criminal jury trials and also opened the door to conducting some civil jury trials using video technology if all parties and the presiding judge are in agreement.” In the U.S. District Courts, no jury trials may commence before Monday March 15, 2021 (U.S. District Court, General Order #25).

Despite the availability of coronavirus vaccines in 2021, numerous factors—from slower-than-optimal vaccine distribution to the specter of possible vaccine-resistant covid strains—suggest that pandemic public health precautions will remain with us for the foreseeable future. And we will need to continue to observe safeguards at every step of the trial process to promote and guarantee the American right to a trial by jury. Lawyers and judges have shown, and will continue to demonstrate, the resilience, creativity, and adaptability required to keep our system working.

KRISTI J. PAULSON is an accomplished trial lawyer with over 25 years of experience in the courtroom. She is a member of the American Board of Trial Advocates (ABOTA) and the director of the Academy of Certified Trial Lawyers of Minnesota (ACTLM). Kristi is a past president of the Douglas J. Amdahl Inn of Court, and serves on both the Minnesota Lawyers Professional Responsibility Board and the ADR Ethics Board. She is also the president of PowerHouse Mediation and Dispute Resolution, providing online and in-person mediation services and CLE and ADR trainings.