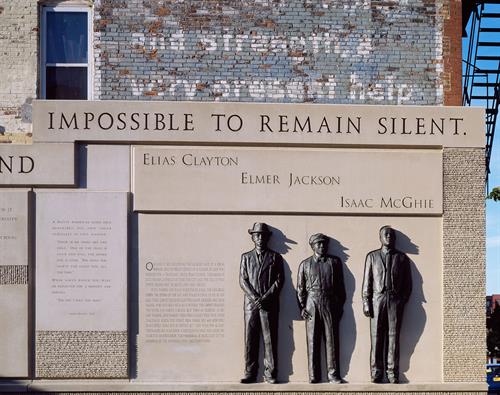

A memorial built in 2003 at the site of the lynchings

A prize-winning Minnesota historian looks at the legacy of the murders 100 years later

By William D. Green

After a lecture I gave in Rochester earlier this year, a man walked up to welcome me to the city and thank me for my remarks. After a brief exchange, he asked me if I planned to go to the June 15 commemoration of the Duluth lynchings. I said that I had other commitments. At the time, I hadn’t fully realized how much of an event it was scheduled to be—not in terms of activities, but the scope of its impact on the community. In the quieter moments of my drive home, I wondered whether I was missing something bigger than the apparently widely anticipated, long-overdue recognition of that tragic event. And this—my reaction, that is—began to perplex me, as well.

In the early ‘90s, when I first began teaching at Augsburg University, I had come across a book entitled, uncomfortably, They Was Just N*****s, taken from a statement that one of the lynchers made in defense of his action. The author, Michael Fedo, a native of Duluth, had selected the title, to the discomfort of his publisher, in order to provoke attention to the incident and the sensibility of Duluthians at the time, as well as to stimulate thoughtful reactions. He definitely succeeded, but not in the way he had hoped. After his public readings, especially in his home city, it was not unusual that people (at least in one place—the public library) had lined up to tell him that in writing the book, he had wrongly aired the city’s “dirty laundry.” They must have felt a sense of justice when the book was allowed to quietly go out of print. Though it had long since vanished from bookshelves, Michael agreed to join me in a panel discussion at the campus.

I secured a classroom but made few preparations for an event I expected to be small. After all, faculty were grumpily grading finals; and as fortune would have it, the day of the event happened to be the first beautiful day of spring, when there would surely be much celebration by students in the park. I was stunned to see the room slowly fill with students, faculty, and even people from the community standing wall-to-wall to hear the story. A conversation scheduled to run for an hour lasted all afternoon because, as it turned out, many people wanted to know more. Some, no doubt, considered what Michael described to be like a parallel universe where people in the mob were completely (and perhaps even safely) foreign; to them the story, while interesting, ultimately had little to say to or about modern Minnesota. Some were drawn to the macabre tale like moths to a flame, and somehow, in turn, felt licensed to luxuriate in their own rectitude. Others still simply wanted to learn, and in doing so, to give tribute in some small way to the memories of Isaac McGhie, Elias Clayton, and Elmer Jackson—and perhaps thereby to extend quiet sorrow and even apologies for the sins of the fathers. But none present was in denial: There was a unanimous recognition that the awful incident had occurred. My gallows humor led me to presume that it was because we weren’t in Duluth; but, really, I wanted to believe that by the time of that discussion, even the older citizens of Duluth had come to acknowledge that chapter in their city’s history.

I was pleased to learn afterward that the Minnesota Historical Society had decided to reissue the book, albeit under the less-provocative title The Lynchings in Duluth. To the credit of the editors, they selected a cover that would leave no doubt as to what the book was about: the infamous black-and-white photograph of two African Americans hanging from the lamp post, a third prone before them, all surrounded by white men mugging for the camera like fishermen displaying their prize catches.

Michael would later recount his father describing the reaction of a long-time friend who had stopped by the house, seen a copy of this new edition on the coffee table, and exclaimed in horror—not as much at the awful image of the three hanged African Americans as at one of the gleeful white faces taking in their triumph: her own beloved father. I wondered what kind of horror a non-relative would feel at the sight of the hangings, or at the thought that the hangings occurred in our state. In 1920, it appeared that right-thinking Minnesotans were shocked for the second reason. They smelled the smoldering embers, but didn’t look to see from where the smoke was coming.

Nationwide, lynchings and mob violence against African Americans had become commonplace. In 1915, The Birth of a Nation drew sell-out crowds at movie theatres, Minneapolis included, giving license to find entertainment in the image of a black man swinging from a tree. Nellie Francis, a black leader at the time, was even more alarmed to hear from white political allies that the film was harmless. The superintendent of Minneapolis schools praised the film for its educational merit. In 1916, the women’s suffrage chapter in Albert Lea used the film to promote the movement.

Meanwhile, the NAACP collected data on racial violence in the country, reporting in 1920 that over the 31-year period from 1889 to 1919, 2,549 black men (most of them accused of raping a white woman) and 51 black women were lynched. During the year of 1919 alone, 78 African Americans were lynched, 11 of whom were ex-soldiers. One was a woman. Fourteen were burned at the stake. Twenty-eight cities staged race riots in which more than 100 black people were killed. And even as some of these facts appeared in newspapers of the day (though less so in the white press), Minnesotans, if they were aware at all, looked on as if those events had occurred on the other side of the moon, assured by the conviction that they were the inheritors of a tolerant and civilized community where such things did not occur. Three months after the report appeared in March 1920, the Duluth mob assembled to commence its deadly work.

The point is, it did not happen spontaneously. The “fire” needed kindling that had been widely spread by the degrading social custom of racial discrimination. But the absence of reported dust-ups between black and white Minnesotans lulled the society into believing that there were no racial problems. Blacks in St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Duluth avoided the indignity of bad service in white-owned establishments and places—including most of the cities’ streets—where they could be subject to harassment and insult. A variation of Jim Crow ruled within much of the North Star State. In effect, the permission to dehumanize had been codified. To avoid the perennial threat of having their dignity affronted, the black middle class was discouraged from being visible while the black working class was reduced to a valueless stereotype. To the passive white observer, the arrangement seemed benign. But at the time, they had no sense of recent history. In 1895 in St. Paul, black men on two separate occasions were nearly lynched, one virtually in the shadow of the state capitol, both to the cheers of a mainstream press that had, only four years earlier, praised a black girl named Nellie Francis for delivering a high school graduation speech on America’s responsibility to address the race problem.

Paradox has always been the key element to understanding race relations. But because Americans have never done well with paradox, we’ve never done well talking about race. We come close by looking at the sensational. And what could be more sensational than the stark duality of race and sex evinced in the Duluth lynchings of 1920? Yet I think the lynchings themselves may paradoxically cloud the elements, not just regarding what happened, but how the events in Duluth demonstrated that the city and state were fundamentally no different from other places where similar tragedies occurred, North and South.

Labor strife had lately intensified in the region, and the city’s largest employer had brought in large numbers of black workers from the South. In the middle of what had already been a hot summer, there were too many young men anxious to show their manhood after being deemed ineligible to serve in the recently concluded “War to End All Wars.” J.A.A. Burnquist, the pro-business Republican governor who had cracked down on radicals, labor activists, and war dissenters, was also president of the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP and thus the friend of my enemy in the eyes of many around Duluth. Readers of local newspapers saw a steady stream of depictions of African American men either as shiftless caricatures or criminals—typically petty thieves or sexual predators of white women, or both, to reinforce the widespread belief in their inherently bestial nature. On a different front, firemen and police officers were frustrated by their own negotiations with the city for better wages. The U.S. Attorney had recently been indicted for smuggling Canadian whiskey. Jailers harassed women prisoners from the working-class neighborhood of West Duluth. During the events of June 15, the mayor was out of town and the police chief sat ensconced in his office on the top floor of the police station, where he would remain throughout the rioting.

During the assault on the jail, officers were ordered not to fire on the encroaching mob. Upstanding citizens watched with amusement as the mob either cut fire hoses about to be trained on them or turned them against the police standing out front. One of the “judges” on the kangaroo court that condemned the prisoners had weeks before written an award-winning high school essay that condemned lynching in America.

Carl Hammerberg, an immigrant teenager of diminished capacity and limited English skills whose curiosity drew him into the wake of the mob as it rampaged through the jail—punching holes in walls, roughing up officers, and passing the black men into waiting hands to be hanged—would become one of only three “culprits” convicted for the crime of rioting. He would likely have shared one of the few cells that had not been destroyed with the only black man who would later be found guilty of raping the young white woman. Meanwhile, a black man coming home from work saw the “excitement” but was told by a nearby white man in the crowd that he best hurry home because the crowd was about to kill some Negroes. As the mob surged forward, a priest futilely called for calm. Later a reporter would liken the doomed men as they were hoisted up to balloons ascending upward over a carnival.

None of the senior officials believed that it could happen in “one of the most racially tolerant, northernmost states in the Union.” County Attorney Warren Greene told jurors at the opening of the first trials that it was incumbent upon the jury system to remove the stain, for the lynchings had lowered Minnesotans to the level of Southerners: It was really, he said, the jury system that was on trial. But with each acquittal, the cheers from outside the courtroom grew in volume, blurring the line between due process and mob law. With the conviction of the immigrant youth and the others by a jury no longer composed of working-class men, boosters of the state hoped that Minnesota’s standing would be rehabilitated. No one was prosecuted for murder. Only one black man was convicted of rape. All other charges were dropped. The city could then decide that this was enough: best (as they say) to let sleeping dogs lie.

Max Mason, the black man found guilty of rape, appealed his conviction before the state Supreme Court, challenging the method by which he was identified by the accuser. The conviction stood, though a dissenting opinion asserted that the identification of Mason was flawed: “It is common knowledge,” wrote Justice Dibbell, “that colored men are not easily distinguished in daytime and less readily in the dark or in the twilight. Young southern negroes, such as [Mason], look much alike to the northerner. The proof is in the case.” The curious yet divergent logic of racial awareness in the opinion and the dissent were like branches of the same tree: The life and soul of black men were immediately devalued because they all looked alike. Accordingly, the whole ugly chapter could now be closed and in the end, no one would get justice. The stain seemed destined to remain due to the system’s failure to pursue justice as well as the community’s insistence to accept this outcome; but redemption, of sorts, did come in the form of the enactment of the state’s antilynching law in the spring of 1921.

This brings me to the Rochester lecture that I mentioned in the beginning. My talk was on the life and times of Nellie Francis, a remarkable African American woman of many accomplishments, starting with her high school graduation speech. She helped to lead the women’s suffrage campaign in Minnesota and later wrote and lobbied the Legislature for passage of the state’s antilynching bill. Her participation in suffrage work represented interracial cooperation at a time when the national leadership of white suffrage organizations was more than willing to compromise the voting rights of black women for the support of the southern Congressional bloc.

This brings me to the Rochester lecture that I mentioned in the beginning. My talk was on the life and times of Nellie Francis, a remarkable African American woman of many accomplishments, starting with her high school graduation speech. She helped to lead the women’s suffrage campaign in Minnesota and later wrote and lobbied the Legislature for passage of the state’s antilynching bill. Her participation in suffrage work represented interracial cooperation at a time when the national leadership of white suffrage organizations was more than willing to compromise the voting rights of black women for the support of the southern Congressional bloc.

But in Minnesota, the formidable Clara Ueland, president of the Women’s Suffrage Association, set a new tone in her organization. For one, there would be no approval given to chapters that wanted to present The Birth of a Nation in order to promote the suffrage movement, and Francis’s role would be more than symbolic. In 1919, Gov. Burnquist signed Minnesota’s certificate of ratification for the 19th Amendment. And in 1921, when Francis launched her lobbying effort, suffragists no doubt provided her with support in securing the needed votes from state legislators, which she, in a most spectacular manner, succeeded in doing. With a vote in the House of 81-1, and in the Senate, 41-0, the bill was signed into law on the 18th of April. Gov. J. A. O. Preus, who succeeded Burnquist, had said even before the bill’s passage that it would be his pleasure to sign it.

It would seem that Minnesota had solidly declared support for racial justice, and in doing so by enacting legislation, it seemed that Minnesotans, through their chosen representatives, had at last, after a year, removed the stain from Duluth and from the state as a whole. Now, unfortunately, it seemed that it was time for high-minded Minnesotans, resting on their laurels of reform, to return to complaisance. In the last year of Preus’s tenure, when Nellie and William Francis purchased a new home that was located in a white neighborhood of St. Paul, the Francises—Minnesota’s champions of racial dignity and opportunity, who had done so much to inspire people to be better than their baser instincts—watched as crosses were burned on their front lawn.

With few exceptions, white friends and allies did not come to their defense. Instead the couple learned one simple message, loudly and clearly: Maybe they could not be lynched and Nellie could vote, but they still had to know their place and stay in it, or else. In 2003 a memorial monument to the victims of lynching was dedicated in Duluth; today, another significant step in removing the stain of the Duluth lynchings begins by reaffirming that it happened, as the commemorations marking the event do. But it must never be a one-dimensional effort to demystify the state’s self-image of exceptionalism. Rather, to have truly learned the lesson of Duluth is to commence a sustained effort to remedy the multifaceted nature of racial inequity.

WILLIAM D. GREEN, J.D., Ph.D., is professor of history at Augsburg University. He is a two-time recipient of the Minnesota Book Award-Hognander Prize—in 2016, for Degrees of Freedom: The Origins of Civil Rights in Minnesota, 1865-1912, and in 2020, for The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity, 1860-1875. His forthcoming biography, Nellie Francis: Fighting for Racial Justice and Gender Equality, will appear in January 2021.