Think MDOLI has settled the issue? Think again.

BY SUE CONLEY AND JEFF MARKOWITZ

There are times in the law when everyone thinks you’re wrong but you just can’t shake the feeling that you’re right. It is a bit jarring, and it can make you (quite reasonably) second-guess yourself. But you double- and triple-check your facts and the law, take a deep breath, and conclude, yes, I got this right.

There are times in the law when everyone thinks you’re wrong but you just can’t shake the feeling that you’re right. It is a bit jarring, and it can make you (quite reasonably) second-guess yourself. But you double- and triple-check your facts and the law, take a deep breath, and conclude, yes, I got this right.

We respectfully suggest that we are in that situation when it comes to whether, through the 2015 promulgated opioid rules, the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry (MDOLI)—by defining medical marijuana that is used consistent with Minnesota law as not an “illegal substance”—made such medical marijuana reimbursable through Minnesota workers’ compensation.

Many attorneys in the workers’ compensation claimant bar, and some workers’ compensation judges, have concluded that MDOLI’s 2015 opioid rules authorized workers’ compensation reimbursement for medical marijuana.1 They point solely to Minnesota Rule 5221.6040, subpart 7a, which defines “illegal substance” as “a drug or other substance that is illegal under state or federal controlled substances law,” but excludes from that definition’s scope “a patient’s use of medical cannabis permitted under Minnesota Statutes, sections 152.22 to 152.37.” They conclude that, in so defining “illegal substance,” MDOLI was approving of courts requiring employers and their insurers to pay workers’ compensation benefits to cover such medical marijuana.

That conclusion is incorrect. The term “illegal substance” that Minn. R. 5221.6040, subp. 7a defines exists nowhere in the Minnesota Workers’ Compensation Act (WCA).2 It exists in only three places in the workers’ compensation treatment parameters, all of which appear in one rule—Minn. R. 5221.6110—that governs long-term use of opioids. The gist of “illegal substance” as defined in that context means that use of medical marijuana consistent with Minnesota law will not disqualify someone from receiving workers’ compensation benefits for opioids—an exception to the general disqualifying effect of using illegal substances while taking opioids.

Even if MDOLI had intended by that rule to authorize reimbursement for medical marijuana under workers’ compensation—it did not—such a rule would nonetheless be invalid. It would be beyond MDOLI’s rulemaking authority, given that possession of medical marijuana generally remains a federal crime under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA),3 and because the Minnesota Legislature—which gave MDOLI its rulemaking authority—cannot require others to aid, abet, or conspire in criminal violations of the CSA.

In this article, we will first address the federal landscape, under which marijuana—even medical marijuana—is illegal for any purpose except for federal government-approved research. Second, we will discuss the impact of Minnesota’s 2014 medical marijuana amendment. Third, we will explain why MDOLI did not intend to—and did not actually—make medical marijuana reimbursable through the WCA.

Federal background

Congress enacted the CSA in 1970 “to conquer drug abuse and to control the legitimate and illegitimate traffic in controlled substances.”4 The CSA does so by imposing harsh criminal penalties.5 It punishes even first-time possession done “knowingly or intentionally,” with a potential prison term of one year minus one day; a fine of at least $1,000; or both.6

Of particular concern to employers and workers’ compensation insurers, those penalties are not reserved for principal actors. The CSA extends “the same penalties as those prescribed for the offense” to any person who “conspires to commit” the offense, when the offense was the conspiracy’s “object.”7 The CSA is also subject to the general aiding-and-abetting statute, under which, whoever “aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces or procures [an offense’s] commission, is punishable as a principal.”8

“In enacting the CSA, Congress classified marijuana as a Schedule I drug.”9 Marijuana has remained on Schedule I, notwithstanding seven petitions to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA)10 to reschedule it to a less restrictive schedule.11 The DEA most recently denied such a petition on August 12, 2016.12 The only qualifier to marijuana’s Schedule I placement came on December 20, 2018, when Congress added the hemp exception through the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (a.k.a. the 2018 Farm Bill).13 As amended, CSA Schedule I substances include “[t]etrahydrocannabinols, except for tetrahydrocannabinols in hemp (as defined under section 1639o of title 7).”14

“By classifying marijuana as a Schedule I drug, as opposed to listing it on a lesser schedule, the manufacture, distribution, or possession of marijuana became a criminal offense, with the sole exception being use of the drug as part of a Food and Drug Administration preapproved research study.”15 In other words, “there is but one express exception, and it is available only for Government-approved research projects.”16

Federal law prohibits doctors from prescribing medical marijuana.17

For all substances on Schedule I of the CSA, Congress expressly found three things: (1) “[t]he drug or other substance has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States”; (2) “[t]he drug or other substance has a high potential for abuse”; and (3) “[t]here is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision.”18 In the DEA’s most recent denial of a petition to reschedule marijuana—the August 12, 2016 denial—the DEA expressly found that marijuana “continues to meet the criteria for schedule I control under the CSA.”19

The United States Supreme Court, in Oakland Cannabis and Raich, has made clear that marijuana’s Schedule I placement leaves no wiggle room for medical marijuana. In Oakland Cannabis (2001), a cooperative of medical-marijuana dispensaries opened up shop to sell medical marijuana, consistent with a California medical-marijuana statute that “create[d] an exception to California laws prohibiting the possession and cultivation of marijuana.”20

The district court issued an injunction that enjoined the dispensaries from distributing medical marijuana, even for medical marijuana that was, according to the cooperative, “medically necessary.”21 “Marijuana is the only drug, according to the Cooperative, that can alleviate the severe pain and other debilitating symptoms of the Cooperative’s patients.”22

The district court concluded that “[a]lthough recognizing that ‘human suffering’ could result,... a court’s ‘equitable powers [do] not permit it to ignore federal law.’”23 Disagreeing, the Ninth Circuit reversed, concluding that the cooperative had a legally cognizable medical-necessity defense that permitted it to distribute medical marijuana.24

The Supreme Court reversed. The Court concluded that “a medical necessity exception for marijuana is at odds with the terms of the Controlled Substances Act.”25 The cooperative argued that “use of schedule I drugs generally—whether placed in schedule I by Congress or the Attorney General—can be medically necessary, notwithstanding that they have ‘no currently accepted medical use.’”26 The Court “decline[d] to parse the statute in this manner.”27 “It is clear from the text of the Act that Congress has made a determination that marijuana has no medical benefits worthy of an exception.”28 “[W]e have no doubt that the Controlled Substances Act cannot bear a medical necessity defense to distributions of marijuana.”29 The Court concluded likewise as to “the other prohibitions in the Controlled Substances Act.”30

Raich (2005) further closed the door on medical marijuana under federal law in the context of California’s medical-marijuana law, but this time dealing with (seriously ill) users rather than dispensaries.31 Two Californians (Raich and Monson) suffered from “a variety of serious medical conditions,” and used medical marijuana, consistent with California law.32 Their licensed, board-certified medical providers concluded that “marijuana is the only drug available that provides effective treatment.”33 “Raich’s physician believe[d] that forgoing cannabis treatments would certainly cause Raich excruciating pain and could very well prove fatal.”34

Raich and Monson moved for a preliminary injunction to enjoin enforcement of the CSA against them.35 The district court denied the motion; the Ninth Circuit reversed and ordered the district court to enter the injunction.36 The Ninth Circuit concluded that the CSA, as applied to Raich and Monson, was “an unconstitutional exercise of Congress’s Commerce Clause authority.”37 It reasoned that “intrastate, noncommercial cultivation and possession of cannabis for personal medical purposes as recommended by a patient’s physician pursuant to valid California state law” is beyond the CSA’s scope.38

The Supreme Court reversed, concluding that “[t]he CSA is a valid exercise of federal power, even as applied to the troubling facts of this case.”39 “[W]e have no difficulty concluding that Congress had a rational basis for believing that failure to regulate the intrastate manufacture and possession of marijuana would leave a gaping hole in the CSA.”40 “[T]he mere fact that marijuana—like virtually every other controlled substance regulated by the CSA—is used for medicinal purposes cannot possibly serve to distinguish it from the core activities regulated by the CSA.”41 “[L]imiting the activity to marijuana possession and cultivation ‘in accordance with state law’ cannot serve to place respondents’ activities beyond congressional reach.”42

Moreover, at least two out-of-state courts have concluded that federal aiding-and-abetting liability may arise even from an employer’s or insurer’s payment of workers’ compensation benefits for medical marijuana authorized by state medical marijuana law, in Maine (Bourgoin) and Massachusetts (Wright).43 No federal courts or Minnesota appellate courts have squarely addressed the issue.

On November 13, 2019, a Minnesota workers’ compensation judge rejected (we believe erroneously) the criminal-liability concerns of an employer and insurer in Musta.44 She appeared to rely solely on a temporary budgetary rider (known as the Rohrabacher-Farr/Rohrabacher-Blumenauer amendment). At the moment, the rider (as interpreted by some courts) prohibits the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) from using Congressional funds made available by the most recent appropriations act to prosecute manufacturers, dispensers, or users of medical marijuana, if compliant with state law.45 The currently applicable rider was scheduled to expire on September 30, 2019, but Congress passed stop-gap continuing resolutions to extend it and other appropriations provisions through November 21, 2019,46and then again through December 20, 2019.47

Such temporary riders—although they generally have been added to appropriations bills since December 201448—do “not provide immunity from prosecution for federal marijuana offenses.”49 “The federal government can prosecute such offenses for up to five years after they occur.”50 As the Ninth Circuit pointedly observed in McIntosh, “Congress could restore funding tomorrow, a year from now, or four years from now, and the government could then prosecute individuals who committed offenses while the government lacked funding.”51 “The Rohrabacher–Farr Amendment... did not repeal federal laws criminalizing the possession of marijuana, 21 U.S.C. §844.”52 Congress appeared likely to include such a rider in the appropriations bill for 2020, when the authors of this article finalized it on December 17, 2019.

Minnesota background

The THC Therapeutic Research Act (THC Act)53 was enacted in 1980.54 When originally enacted, the THC Act did not authorize the use of medical marijuana. Rather, the Minnesota Legislature authorized that use by amendment in 2014. Through the 2014 amendment, the Legislature created a patient registry program, through which qualifying patients could apply to the Minnesota Commissioner of the Department of Health for authorization to buy medical marijuana,55 from one of two registered manufacturers in Minnesota, LeafLine Labs or Minnesota Medical Solutions.56

A central requirement for a successful medical-marijuana application is that the patient provide a “certification” from his health-care provider, stating she has been “diagnosed with a qualifying medical condition.”57 The 2014 amendment codified nine qualifying conditions: (1) glaucoma; (2) HIV and AIDS; (3) Tourette’s syndrome; (4) amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; (5) seizures, including those characteristic of epilepsy; (6) severe and persistent muscle spasms, including those characteristic of multiple sclerosis; (7) inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease; and, with some qualifiers that require additional symptoms, (8) cancer and (9) terminal illnesses with a probable life expectancy of less than one year.58 The amendment also gave the Commissioner authority to add qualifying conditions.59 The Commissioner has added seven: (1) intractable pain; (2) post-traumatic stress disorder; (3) autism; (4) obstructive sleep apnea; (5) Alzheimer’s Disease;60 and, most recently—announced on December 2, 2019, effective August 2020—(6) chronic pain and (7) age-related macular degeneration.61

Worth noting is the way in which the 2014 amendment “legalized” medical marijuana. It did not remove marijuana from Schedule I of Minnesota’s own controlled-substance statutes and rules—marijuana remains there today.62 Nor did the amendment permit doctors to prescribe marijuana; Minnesota doctors still cannot legally do so under state law.63 Notably, shortly after the amendment’s approval, the Minnesota Court of Appeals concluded in Thiel that “a defense of medical necessity is [still] not available in Minnesota for a defendant charged with a controlled-substance crime.”64 The court cited with approval its Hanson opinion (1991), in which it concluded, by placing marijuana on Minnesota’s own Schedule I, the Legislature “implie[d] a determination that marijuana has ‘no currently accepted medical use in the United States.’”65

Rather, the Minnesota Legislature “legalized” medical marijuana by codifying various back-end protections.66 For example, the Legislature made “use or possession of medical cannabis or medical cannabis products by a patient enrolled in the registry program” “not [a] violation[] under” Minnesota’s controlled-substances statutes in Minnesota Statutes Chapter 152.67 In a similar vein, the Legislature essentially immunized State of Minnesota personnel from civil and criminal liability for their roles in the program, and it protected “health care practitioner[s]” and Minnesota Department of Health personnel from civil or disciplinary penalties based solely on their program participation.68 In related fashion, the Legislature guaranteed that nothing in “sections 152.22 to 152.37” of the THC Act would “require medical assistance and MinnesotaCare to reimburse an enrollee or a provider for costs associated with the medical use of cannabis.”69

The 2014 amendment included no such protection for employers or their workers’ compensation insurers. Nor, however, did it purport to require employers or their insurers to reimburse employees for medical marijuana, through workers’ compensation or otherwise.

The amendment was silent on the issue.

That brings us to the heart of this article: Minn. R. 5221.6040, subp. 7a.

The Minnesota WCA; the 2015 opioid rules; and the definition of “illegal substance” in MDOLI’s rule

A question that Minnesota workers’ compensation lawyers and judges have been struggling with (in recent and active litigation) is whether the general duty to pay workers’ compensation benefits imposed by the WCA70 extends to require employers and their workers’ compensation insurers to reimburse an employee for medical marijuana that she buys and uses in a manner compliant with Minnesota law (even though it is otherwise federally illegal). Nowhere in the WCA does the Legislature mention medical marijuana or the THC Act’s 2014 amendment that permitted medical marijuana for qualifying conditions.

However, MDOLI mentioned both when it promulgated the 2015 opioid rules. That caught the attention of a number of Minnesota workers’ compensation lawyers—and at least a few judges. MDOLI did so in the newly added definition of “illegal substance.” That definition led some legal observers to (mistakenly) conclude that this was MDOLI approving of employers and insurers reimbursing an employee for her purchase of medical marijuana, as long as the employee’s use complied with the THC Act’s 2014 amendment.71

In our view, this popularized view cannot be sustained by the plain text and context of Minn. R. 5221.6040, subp. 7a. Further, MDOLI itself refuted this view in August 2015, shortly after promulgating Minn. R. 5221.6040, subp. 7a, effective on July 13, 2015.

Minnesota Rule 5221.6040, subpart 7a, simply defines “illegal substance.” Definitions do nothing, apart from the terms that they define, when used. The rule defines “illegal substance” as “a drug or other substance that is illegal under state or federal controlled substances law,” but excludes from that definition’s scope “a patient’s use of medical cannabis permitted under Minnesota Statutes, sections 152.22 to 152.37.” But the term “illegal substance” appears nowhere in the WCA. Moreover, Subpart 1 of that same Rule 5221.6040 (Scope) states that the definitions set forth in Rule 5221.6040 serve to define “[t]he terms used in parts 5221.6010 to 5221.6600.”

The term “illegal substance” appears in only one of those rules: Minn. R. 5221.6110—the opioid rule—which “govern[s] long-term opioid medication.”72 Rule 5221.6110 provides “detailed substantive and procedural requirements that physicians must follow in treating workers’ compensation patients with opioid pain medications.”73

In the opioid rule, “illegal substance” appears three times: in Rule 5221.6110, Subparts 4(F), 7(I)(2), and 8(F)(1). The gist is that, generally, use of illegal substances will disqualify a patient from opioids, except if the illegal substance is medical marijuana.74

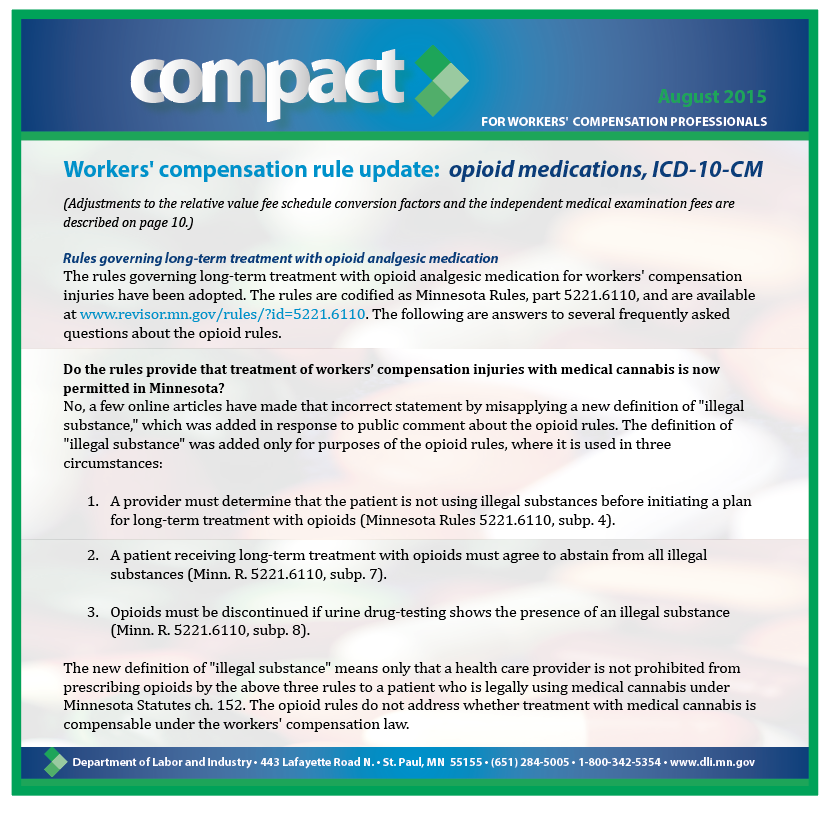

MDOLI explained the matter fully in its August 2015 issue of COMPACT, in which it refuted the view that the definition of “illegal substance” in Minn. R. 5221.6040, subp. 7a, and the opioid rules made medical marijuana reimbursable through Minnesota workers’ compensation.75 No pre-2016 issue of COMPACT is available through MDOLI’s online archives.76 Thus we include a screen shot from the August 2015 issue, which refuted the erroneous view that the July 2015 opioid rules made medical marijuana

reimbursable.

In short, contrary to seemingly popular belief, the opioid rules are just about opioids. They did not, nor did MDOLI intend them to, address whether employers and insurers must reimburse a Minnesota-law-compliant employee for medical marijuana, where such reimbursement (at least arguably) compels the employer and insurer to commit federal crimes by aiding, abetting, and conspiring to further possession of marijuana.

Whether the WCA compels such reimbursement is, at least, an open question.77

Working alongside insurers, employers, and self-insured entities, SUE CONLEY works to resolve workers’ compensation and general liability cases, and has done so for more than 25 years. She has a special interest in complex issues involving medical marijuana, occupational exposure, traumatic brain injury, and complex medical claims.

JEFF MARKOWITZ has a special interest in helping clients navigate tough issues, including those implicated by medical marijuana. He focuses his practice primarily on business and employment law, as well as a busy appellate practice. He clerked for the Minnesota Court of Appeals, and enjoys guest judging mock arguments.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Jirak, Laurie, “DLI NOT BLOWING SMOKE: MEDICAL MARIJUANA VALID WORKERS’ COMP EXPENSE,” 25 No. 7 Minn. Emp. L. Letter 1 (Sept. 2015) (“Medical marijuana is now a permissible and reimbursable treatment for workplace injuries, according to the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry (DLI).”); Farrish Johnson Law Office, “Medical Marijuana in a Workers’ Compensation Case,” https://www.farrishlaw.com/medical-marijuana-in-a-workers-compensation-case/, last visited 12/3/2019; Puechner, Nic., Larkin Hoffman, “Minnesota Worker’s Compensation Claims Involving Medical Marijuana https://www.employmentandlaborlawblog.com/2019/02/minnesota-workers-compensation-claims-involving-medical-marijuana/, last visited 12/3/2019.

2 Minn. Stat. §§176.001-.862.

3 21 U.S.C. §§801-904.

4 Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1, 12 (2005).

5 21 U.S.C §841(b) (potential sentences of 10 to 20 years and stiff fines).

6 21 U.S.C. §844(a).

7 21 U.S.C. §846.

8 18 U.S.C. §2(a).

9 Raich, 545 U.S. at 14.

10 The CSA gave authority to reschedule drugs to the U.S. Attorney General, and the Attorney General delegated that authority to the head of the DEA. Washington v. Barr, 925 F.3d 109, 115 n.3 (2d Cir. 2019) (citing 21 U.S.C. §811(a); 28 C.F.R. §0.100(b)).

11 Washington v. Sessions, No. 17 CIV. 5625 (AKH), 2018 WL 1114758, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. 2/26/2018) (quoting Raich, 545 U.S. at 15), appeal held in abeyance sub nom. Washington v. Barr, 925 F.3d 109 (2d Cir. 2019).

12 Denial of Petition To Initiate Proceedings To Reschedule Marijuana, 81 FR 53767-01, 2016 WL 4240243 (F.R. 8/12/2016).

13 AGRICULTURE IMPROVEMENT ACT OF 2018, PL 115-334, 12/20/2018, 132 Stat 4490, §12619(b).

14 21 U.S.C. §812, Schedule I(c)(17).

15 Raich, 545 U.S. at 14 (citing 21 U.S.C. §§823(f), 841(a)(1), 844(a); United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative, 532 U.S. 483, 490 (2001)).

16 Oakland Cannabis, 532 U.S. at 490.

17 Oakland Cannabis, 532 U.S. at 491; United States v. Evans, 892 F.3d 692, 699 (5th Cir. 2018) (“Schedule I drugs... are deemed to have no medical use and thus cannot be legally prescribed under federal law.”); 21 U.S.C. 829 (“Prescriptions,” listing Scheduling II, III, IV, and V substances, but not Schedule I substances).

18 21 U.S.C. §812(b)(1).

19 Denial of Petition, 81 FR 53767-01, at *53767.

20 Oakland Cannabis, 532 U.S. at 486.

21 Id. at 488.

22 Id. at 487.

23 Oakland Cannabis, 532 U.S. at 487-88.

24 Id.

25 Id. at 491.

26 Id. at 493.

27 Id.

28 Id.

29 Id. at 494.

30 Id. at 495 n.7.

31 Raich, 545 U.S. at 5.

32 Id. at 6-7.

33 Id. at 7.

34 Id.

35 Id. at 7-8.

36 Id. at 8 & n.8.

37 Id. at 8 (quotation omitted).

38 Id. (quotation omitted).

39 Id. at 9.

40 Id. at 22.

41 Id. at 28.

42 Id. at 29.

43 See Bourgoin v. Twin Rivers Paper Co., LLC, 187 A.3d 10 (Maine 2018); Daniel Wright, Employee Pioneer Valley, Employer Cent. Mut. Ins. Co., Insurer, No. 04387-15, 2019 WL 3323160 (Mass. Dept. Ind. Acc. 2/14/2019). But see Appeal of Panaggio, 205 A.3d 1099 (N.H. 2019); Lewis v. American General Media, 355 P.3d 850 (N.M. Ct. App. 2015); Vialpando v. Ben’s Auto. Servs., 331 P.3d 975 (N.M. Ct. App. 2014).

44 Susan K. Musta, Employee v. Mendota Heights Dental Center and Harford Insurance Group, Employer/Insurer, OAH Case No. 7750318-MR-2327 (11/13/2019) (J. Kirsten Tate).

45 PL 116-6, H.J.Res.31, 133 Stat 13, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019, Div. C, Title II, §537. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-joint-resolution/31/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.J.Res.31%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1, last visited 12/3/2019; see United States v. McIntosh, 833 F.3d 1163, 1169 (9th Cir. 2016) (rider barred prosecutions of medical-marijuana users); Marin All. for Med. Marijuana, 139 F. Supp. 3d 1039, 1044-45 (N.D. Cal. 2015) (rider barred prosecutions of dispensaries); see also United States v. Jackson, 388 F. Supp. 3d 505, 510-14 (E.D. Pa. 2019) (rider barred DOJ involvement in prosecuting criminal defendant for violating terms of supervised release).

46 H.R.4378 Continuing Appropriations Act, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/4378/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.R.+4378%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=10, last visited 12/3/2019.

47 H.R.3055, Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3055/text?r=25&s=3, last visited 12/3/2019.

48 McIntosh, 833 F.3d at 1169.

49 Id. at 1179 n.5.

50 Id. (citing 18 U.S.C. §3282).

51 Id.

52 United States v. Tote, No. 1:14-MJ-00212-SAB, 2015 WL 3732010, at *2 (E.D. Cal. 6/12/2015); see Coats v. Dish Network, LLC, 350 P.3d 849, 853 n.2 (Co. 2015) (Rohrabacher-Farr rider did not change fact that “medical marijuana use remains prohibited under the CSA”).

53 Minn. Stat. §§152.21-.37.

54 See Minn. Stat. §152.21, subd. 7; 1980 Minn. Laws, ch. 614, §93.

55 Minn. Stat. §152.27.

56 Minnesota Department of Health, “Medical Cannabis Manufacturers/Laboratories,” https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/cannabis/manufacture/index.html, last visited 12/3/2019; see Minn. Stat. §§152.25, subd. 1(a), 152.30(c).

57 Minn. Stat. §152.27, subd. 3(4).

58 Minn. Stat. §152.22, subd. 14(1)-(9).

59 Minn. Stat. §152.22, subd. 14(10).

60 Minnesota Department of Health, “Medical Cannabis Qualifying Conditions,” https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/cannabis/patients/conditions.html, last visited 12/3/2019.

61 Minnesota Department of Health, News Release (12/2/2019), https://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2019/cannabis120219.html, last visited 12/3/2019.

62 Minn. Stat. §152.02, Schedule I(h); Minn. R. 6800.4210, Schedule I(C)(17), (C)(25); State v. Thiel, 846 N.W.2d 605, 613 n.2 (Minn. App. 2014), review denied (Minn. 8/5/2014).

63 Minn. Stat. §§152.11-.12 (not authorizing Schedule I prescriptions); Thiel, 846 N.W.2d at 613 n.2 (“Even under the legislation recently approved by the state legislature, medical cannabis is not prescribed by health care practitioners.”).

64 Thiel, 846 N.W.2d at 613 n.2, 615 (citing State v. Hanson, 468 N.W.2d 77, 78-79 (Minn. App. 1991), review denied (Minn. 6/3/1991)).

65 Hanson, 468 N.W.2d at 78 (quoting Minn. Stat. §152.02, subd. 7(1)).

66 Minn. Stat. §152.32, subd. 2.

67 Minn. Stat. §152.32, subd. 2(a)(1).

68 Minn. Stat. §152.32, subd. 2(c)-(d).

69 Minn. Stat. §152.23(b).

70 Johnson v. Darchuks Fabrication, Inc., 926 N.W.2d 414, 420 (Minn. 2019) (quoting Minn. Stat. §176.021, subd. 1); Gamble v. Twin Cities Concrete Prod., 852 N.W.2d 245, 248 (Minn. 2014) (quoting Minn. Stat. §176.135, subds. 1a, 6).

71 Supra, note 1.

72 Tina Castro, Employee/respondent, No. WC16-5958, 2017 WL 357246, at *4 (Minn. Work. Comp. Ct. App. 1/9/2017).

73 Johnson, 926 N.W.2d at 418.

74 See Minn. R. 5221.6110, subps 4.F. (requiring prescribing health-care provider to ensure that a qualitative urine drug test confirms that the opioid patient is “not using any illegal substances”), 7(I)(2) (opioid patients must enter into a written treatment contract in which they agree to “abstain from all illegal substances”); 8(F)(1) (opioid patient fails urine drug testing “if it shows the presence of an illegal substance”).

75 COMPACT is a quarterly publication for workers’ compensation professionals, published by MDOLI’s Workers’ Compensation Division. https://www.dli.mn.gov/business/workers-compensation/work-comp-compact-newsletter-archive, last visited 12/3/2019.

76 See id.

77 So too is the closely related question of whether the federal CSA and aiding-and-abetting laws would preempt—and thereby supersede and displace—any state law that purported to require employers and insurers to pay workers’ compensation benefits to reimburse an employee for medical marijuana. That would be the case, in our opinion, as we have written on previously. Conley, Susan K.H., and Markowitz, Jeffrey M., “Pot for Pain: A Courtroom Conundrum in Workers’ Compensation,” For the Defense, DRI (Oct. 2019), https://www.arthurchapman.com/files/original/2019-10%20A%20Courtroom%20Conundrum%20in%20Workers’%20Compensation%20Article%20FTD-1910-Conley-Markowitz.pdf, last visited 12/3/2019. If the Legislature lacks the authority to compel others to aid, abet, and conspire to further federal crimes through statutes, so does MDOLI through its rules, which have no more authority than that which the Legislature delegated to it.