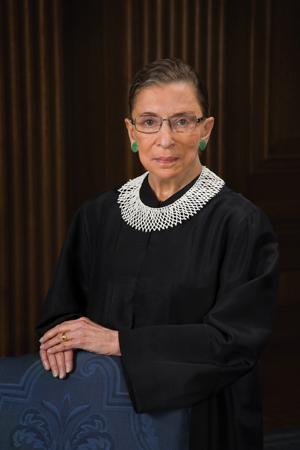

As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg observes her silver anniversary on the U.S. Supreme Court, we look at some of her notable opinions in Minnesota cases.

As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg observes her silver anniversary on the U.S. Supreme Court, we look at some of her notable opinions in Minnesota cases.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in the midst of her 25th term on the U.S. Supreme Court, has become an iconic figure. A documentary about her, RBG, won strong reviews and did well at the box office and in TV ratings when shown on CNN last summer.

Another movie, this one a Hollywood biopic starring the award-winning British actress Felicity Jones, was similarly well-received when it came out near the end of 2018. On the Basis of Sex dramatizes Justice Ginsburg’s work as a civil rights attorney in the 1970s, when she took on and prevailed in ground-breaking gender discrimination cases, co-authoring the prevailing brief in Reed v. Reed.1 This was the first time the high court recognized gender discrimination as a violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment; the film also depicts her successful oral argument in Moritz v. Commissioner of lnternal Revenue,2 which applied that concept in a case concerning discrimination against men denied tax deductions for in-home care they provided even as women care-givers were allowed the deduction.

Those cases jump-started her career as a high profile litigator, mainly dealing with women’s rights, before her appointment to the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, where she served for 13 years prior to being appointed to the Supreme Court shortly before the beginning of the 1994-95 term.

In recent years, she has gained unusual renown for a Supreme Court jurist. Some years ago, a poll indicated that more American adults could name the Three Stooges than could identify a single member of the Supreme Court. But Justice Ginsburg, who makes a concluding cameo in the Hollywood film, has broken through that name recognition barrier.

Justice Ginsburg’s heightened identity is attributable to several factors: her background of overcoming discrimination due to gender and religion; her outgoing personality; and, more fundamentally, the quality of her written opinions, especially some of her dissents. One of those dissents, in an equal pay discrimination case called Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,3 provided the fodder for a subsequent law that extended the statute of limitations for gender disparity claimants.4

Having recovered from three broken ribs suffered in an early November fall in her office and then removal of two cancerous nodes on her lungs a month later, she is the oldest justice currently serving. But Justice Ginsburg, who is turning 86 in March, remains at the height of her jurisprudential skills and public acclaim in most quarters as she and her colleagues begin rolling out rulings in the 2018-19 term.

As Justice Ginsburg proceeds with her silver anniversary on the high court, her impact has gone well beyond the gender discrimination focus of her pre-judicial career portrayed in cinema, as reflected in this eclectic collection of real Minnesota cases.

CONCLUDED CASES

The 2017-18 term that concluded last summer featured a pair of cases from Minnesota, both raising constitutional law issues—though neither elicited a written utterance from Justice Ginsburg.

In Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky,5 138 S.Ct. 1876 (2018), she joined without comment the seven-member majority ruling authored by Chief Justice Roberts, invalidating on 1st Amendment vagueness grounds a Minnesota law, Minn. Stat. §211B.11, subd 1, that barred wearing “political badges or apparel at voter polling places.” She strayed from her usual alliance with the liberal wing of the Court, two of whom (Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer) dissented, writing that the State Supreme Court should have been asked to clarify its interpretation of the statute.

Likewise, in Sveen v. Melin, 138 S.Ct. 1815 (2018), she was a silent member of the 8-1 majority that upheld the Minnesota law automatically revoking a divorced spouse as a life insurance beneficiary under Minn. Stat. §524.2-804, subd. 1, which was challenged under the “impairment of contract” clause of Article I, Section 10, of the federal Constitution, which bars any state law “impairing” a contractual obligation. Only Justice Neil Gorsuch dissented from the majority opinion written by Justice Elena Kagan, reversing an 8th Circuit holding that had overturned a decision by U.S. District Court Judge Paul Magnuson. Agreeing with Judge Magnuson, SCOTUS upheld the retroactive application of the Minnesota law to a divorced spouse four years after the policy was initially purchased.

FIRST FORAYS

Not long after her investiture on the high court, Justice Ginsberg made her first foray into Minnesota jurisprudence. She started meekly with an unusual written concurrence in a denial of certiorari (a process almost always devoid of written opinions) in Davis v. Minnesota.6Writing near the end of her first year on the bench, she concurred with the refusal to hear a challenge of a prosecutor’s attempt to peremptorily strike an African American and member of the Jehovah’s Witness faith as a juror in a robbery case in Ramsey County District Court. She explained that certiorari was improper because the existing rule limiting exclusion of jurors on racial grounds did not “extend to religious affiliation.”

Three years passes before she really made her mark in a Minnesota case, and it was a big one. In U.S. v. O’Hagan,7 a criminal securities trading fraud case against a prominent Minneapolis lawyer, she authored a lengthy opinion for the unanimous Court. The decision by Justice Ginsberg, who has shown an affinity for securities cases, overturned reversal of the verdict by the 8th Circuit on grounds that “trading on the basis of material, non-public information [does] involve a breach of duty of confidentiality” that gives rise to criminal culpability. Justice Ginsburg’s decision for the Court adopted a broad “misappropriation theory” extending to any material “deception” in connection with a securities transaction, even in the absence of “an identifiable purchaser or seller.”

She followed that decision with another majority opinion during the next term in Regions Hospital v. Shalala.8 On behalf of a 6-3 majority, her opinion upheld the right of the government to “re-audit” a hospital’s entitlement to reimbursement for certain costs incurred under the Medicare program. This time, she affirmed an 8th Circuit ruling that the “re-audit” was not impermissibly retroactive.

A decade passed before Justice Ginsburg delivered another majority decision in a Minnesota case. Greenlaw v. United States9 overturned a decision of the 8th Circuit making a sua sponte 15-year increase in the sentence of a Minnesota gang member convicted of multiple drug and firearms offenses, without any request by the government to do so. In a 7-2 ruling, she reasoned that the trial court’s mistake in calculating the sentence too lightly for several drug and firearms offenses did not justify the appellate court departing from the “requisite role of neutral arbitrator of matters the parties present” in advance of a cross-appeal by the government. Since the government had not appealed the sentence imposed by U.S. District Court Judge Joan Ericksen in Minnesota, there “was no occasion” for the court of appeals to tack on 15 years to the lower court’s determination.

CONCURRING CASES

The 2008 Greenlaw case was the last Minnesota matter to date in which Justice Ginsburg has written the majority decision. But she has concurred in several others.

In Raygor v. Regents of University of Minnesota,10 she delivered the decisive vote by concurring in a desultory 5-4 decision involving the University of Minnesota, a first-time litigant before the high court. The case posed a rather mundane issue of supplemental federal court jurisdiction over a state law claim coupled with a defective federal law claim challenging the compulsory early retirement program for university faculty. The issue—whether the statute of limitations was tolled in the state law claim during the pendency of the federal claim—was resolved in the negative by the Minnesota Supreme Court, which had reversed a ruling of the court of appeals overturning a dismissal by the Hennepin County District Court. The high court affirmed, and Justice Ginsburg’s concurrence argued that the applicable statute for supplemental jurisdiction over state law claims, 28 U.S.C. §1367(a), does not express an intent to toll in

“unmistakably clear… language.”

Justice Ginsburg issued one of four concurring decisions late in the 2015-16 term in U.S. Army Corps of Engineers v. Hawkes Co., Inc.,11 in which the justices unanimously held that a jurisdiction decision by the Army Corps of Engineers under the Clean Water Act is reviewable as a “final agency action” under the Federal Administrative Procedure Act, §5 U.S. §704. Her concurrence only addressed one matter: a disinclination to rely upon a claimed agreement between the Corps and the government because of the scant briefing on the issue.

She concurred a month later in consolidated DWI litigation entitled Birchfield v. North Dakota,12 which included a Minnesota case, Bernard v. Minnesota. A unanimous Court ruling established that law enforcement personnel may conduct warrantless breath tests of suspected intoxicated drivers, but must obtain a warrant for “more intrusive blood testing.” Justice Ginsburg joined the concurrence of Justice Sonia Sotomayor, which observed that law enforcement officers must have “tools to combat drunk driving,” while fretting that the extension of “warrantless searches” undermines the 4th Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures.

DISSENTING DECISIONS

It may be Ginsburg’s dissents that are most enduring, like the one in the Ledbetter litigation. She was one of three dissenters in Minnesota v. Carter,13 in which the Court reversed the Minnesota Supreme Court and upheld a warrantless search of a pair of visitors to a facility where cocaine was being distributed. While the majority rejected a 4th Amendment defense, she lamented in the dissent that the ruling “undermines… the security of short term guests [and]… the home resident, as well.”

She also dissented from a five-member majority in opining in favor of a rule prohibiting candidates for state judicial offices from expressing views on controversial issues in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White.14 The “announce” rule was stricken by a one-member majority of the Court for violating the 1st Amendment, although Justice Ginsburg was one of four dissenters who would have affirmed the 8th Circuit ruling upholding the proscription in order to assure “an independent, impartial judiciary.”

MARSHALL H. TANICK is an attorney with the Twin Cities law firm of Meyer Njus Tanick.

CATHY GORLIN is an attorney with the Minneapolis law firm of Best & Flanagan. Married to each other, they were inspired to write this article after meeting Justice Ginsburg at a Supreme Court admissions ceremony for Cathy, also attended by her husband as a previous high court admittee.