A recent appellate decision throws a fledgling industry into chaos

By Jason Tarasek

Imagine, if you will, a place where you could walk into a retail storefront and be presented with a wide variety of marijuana products for sale. If you ever travel beyond Minnesota’s borders, you know these places exist. For example: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, the District of Columbia, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam. Indeed, the countries of Canada, Mexico, South Africa, Uruguay, and Germany have also legalized adult-use marijuana.

Yet, here in Minnesota adult-use marijuana remains illegal and likely will remain illegal for the near future. Why? It’s complicated.

Unlike most states that have legalized adult-use marijuana, Minnesota lacks a citizen-led ballot initiative process. Rather, the Legislature and governor would need to each approve placement of a legalization initiative on the ballot. Alternatively, as with the passage of any law, the Legislature and governor could legalize adult-use marijuana. Recent efforts to pass such legislation, however, have met resistance from Minnesota Republicans.

In April 2019, for example, the Minnesota Senate Judiciary Committee defeated legislation that would have legalized adult-use marijuana in Minnesota. All Democrats on the committee voted in favor; all of the committee’s Republican majority opposed the measure.

On the heels of that defeat, DFL House Majority Leader Ryan Winkler (DFL-Golden Valley) embarked on a “Be Heard on Cannabis” listening tour throughout Minnesota to gauge public interest in legalization. Unsurprisingly, during town halls conducted over the summer of 2019 in Eden Prairie, Shakopee, New Brighton, and elsewhere, Minnesotans overwhelmingly voiced support for legalization.

In the fall of 2019, therefore, Winkler introduced House File 600 to legalize marijuana. Ultimately, the bill passed the DFL-controlled House but was rejected by the GOP-controlled Senate. Republican opposition to legalization could be rooted in legitimate public policy grounds but also may be based on the electoral-politics advantage that the GOP enjoys so long as marijuana remains illegal.

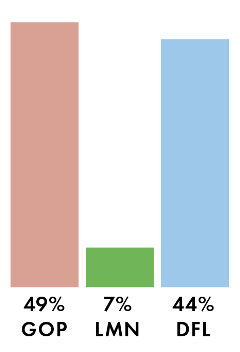

In addition to the DFL and GOP, Minnesota has two other major political parties with a singular focus on marijuana legalization. As of 2018, based on the performance of their candidates for statewide office, the Legal Marijuana Now party (LMN) and the Grassroots-Legalize Cannabis party (GLC) each qualified for major party status. Although these “pot parties” were ostensibly formed to support legalization, they may now actually be impeding legalization. Indeed, if pot-party candidates had not siphoned votes from DFL candidates in 2020, the DFL might well have seized control of the Minnesota Senate. Consider, for example, Sen. Gene Dornink’s (R-Hayfield) 49-44 percent victory over his DFL opponent in a race where the LMN candidate attracted 7 percent of the vote. Would enough LMN votes have gone to the DFL candidate to change the outcome? Maybe. Maybe not. You can see, however, that the presence of the LMN candidate was an important factor in tipping the scales in favor of the GOP.

In addition to the DFL and GOP, Minnesota has two other major political parties with a singular focus on marijuana legalization. As of 2018, based on the performance of their candidates for statewide office, the Legal Marijuana Now party (LMN) and the Grassroots-Legalize Cannabis party (GLC) each qualified for major party status. Although these “pot parties” were ostensibly formed to support legalization, they may now actually be impeding legalization. Indeed, if pot-party candidates had not siphoned votes from DFL candidates in 2020, the DFL might well have seized control of the Minnesota Senate. Consider, for example, Sen. Gene Dornink’s (R-Hayfield) 49-44 percent victory over his DFL opponent in a race where the LMN candidate attracted 7 percent of the vote. Would enough LMN votes have gone to the DFL candidate to change the outcome? Maybe. Maybe not. You can see, however, that the presence of the LMN candidate was an important factor in tipping the scales in favor of the GOP.

In other contests, pot-party candidates attracted a share of votes that exceeded the GOP margin of victory in a Minnesota House race and in the battle that sent GOP Rep. Jim Hagedorn to the U.S. Congress. Indeed, Democrat U.S. Rep. Angie Craig only defeated her opponent by 2 percentage points while a pot-party candidate attracted 6 percent of the vote.

While some of these cannabis-party candidates may be independently choosing to seek office, some candidates have indicated that they were encouraged by Republicans to run. Following the 2020 election, one pot-party candidate told reporters that he was recruited by a “Republican operative” to run in the race that resulted in the election of former GOP state Sen. Michelle Fischbach to the U.S. Congress. According to a June 15, 2020 article in the Minnesota Reformer, the LMN candidate who ostensibly opposed Sen. Dornink posted a pro-Dornink video and was an outspoken supporter of former President Trump.

Whatever the reason for the ongoing GOP opposition to legalization, it is unlikely that the DFL will control the House, Senate, and governorship in the near future. That may mean that the legalization of adult-use marijuana in Minnesota is still several years off. But it doesn’t mean that legal battles over cannabis, hemp, and their various products are years away. They are here.

A brief history of cannabis in America

Cannabis has been cultivated and used by people for thousands of years. In ancient China and Mesopotamia, it was used for rope, sail cloth, and textiles. Native Americans used cannabis for thread, clothing, and food. American colonists grew hemp and exported it to England. In early America, hemp was used for paper, textiles, and rope.

Marijuana was not widely used as a drug in the United States until the 20th Century. Following the Mexican Revolution in 1910, Mexicans began moving to the United States and they brought marijuana with them. In response to these newcomers, anti-Mexican resentment arose. Many states began outlawing marijuana and, in 1937, the federal government essentially banned hemp and marijuana by imposing a $100 tax on sales of the plant.

Cannabis made a brief comeback during World War II, but the government shut it down again after the war. The 1952 Boggs Act and the 1956 Narcotics Control Act established mandatory sentences for drug-related violations; a first-time offense for marijuana possession carried a minimum sentence of 2-10 years in prison and a fine of up to $20,000. Although those penalties were largely repealed by the early 1970s, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 reinstated stiff federal penalties for a variety of marijuana offenses.

In 1970, the federal government adopted the Controlled Substances Act to regulate the manufacture and distribution of drugs. The Act places drugs in five categories, or “schedules,” depending upon the following perceived characteristics of the drug: (1) potential for abuse, (2) safety, (3) addictive potential, and (4) whether or not it has any legitimate medical applications. Among the Schedule One drugs deemed most dangerous of all are LSD, heroin—and marijuana. Schedule Two drugs, which are less restricted than marijuana, include cocaine, codeine, OxyContin, and methamphetamine.

Schedule One drugs are those substances that, in the government’s opinion, have a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use. The irony here is manifest: In 1996, California became the first state to allow medical marijuana and since then more than 30 states, including Minnesota, have adopted medical-marijuana programs.

Minnesota’s medical marijuana program

Minnesota’s medical-marijuana program, approved in 2014, continues to be one of the most restrictive in the country. The conditions that enable patients to qualify for Minnesota’s program include:

- cancer associated with severe/chronic pain, nausea or severe vomiting, or cachexia or severe wasting;

- glaucoma;

- HIV/AIDS;

- Tourette’s Syndrome;

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS);

- seizures, including those characteristic of epilepsy;

- severe and persistent muscle spasms;

- Crohn’s disease;

- terminal illness;

- intractable pain;

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD);

- autism;

- obstructive sleep apnea;

- Alzheimer’s Disease;

- chronic pain;

- sickle cell disease; and

- chronic motor or vocal tic disorder.

To obtain medical marijuana in Minnesota, a new patient must meet with a doctor, who “certifies” a patient as one who suffers from one of the above-identified qualifying conditions. Minnesota doctors do not prescribe marijuana. Rather, once a patient is “certified,” they meet with a cannabis pharmacist at a medical dispensary to obtain a prescription. Nearly 30,000 patients are currently enrolled in the state’s medical cannabis program. About 62 percent are in the program for chronic pain, 42 percent for intractable pain, and nearly 30 percent for PTSD. (Some patients are enrolled for multiple conditions.) The average medical marijuana patient is roughly 46 years old. Because medical marijuana is not covered by health insurance, patients must pay out of pocket. It is not unusual for patients to pay several hundred dollars each month for their medicine. With the recent legalization of sales of raw “flower” to patients, prices are expected to drop yet continue to exceed those found on the illicit market.

CBD, Delta 8, and the growing legal battles over hemp-derived products

In terms of legal cannabis, Minnesota also allows the growing, processing, and sale of hemp and hemp-derived products. Marijuana and hemp come from the same plant, cannabis sativa L. Typically, hemp plants are shorter and bushier than tall, thin marijuana plants. The only pertinent difference between marijuana and hemp, however, involves a legal distinction related to the concentration of Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (often known simply as Delta 9). Hemp is defined as having 0.3 percent or less Delta 9; marijuana is defined as anything with more than 0.3 percent Delta 9.

In 2014, the same year that Minnesota approved its medical-marijuana law, the federal government adopted the 2014 Farm Bill, which provided that “[n]otwithstanding the Controlled Substances Act… or any other Federal law, an institution of higher education… or a State department of agriculture may grow or cultivate industrial hemp,” provided it is done “for purposes of research conducted under an agricultural pilot program or other agricultural or academic research” and those activities are allowed under the relevant state’s laws.1

The 2014 Farm Bill defined “industrial hemp” as the plant Cannabis sativa L. or any part of such plant, “with a delta-9 THC concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”2

On December 20, 2018, President Trump signed the 2018 Farm Bill, which distinguished hemp from marijuana and removed hemp from federal controlled substance schedules. The bill also expanded the definition of “industrial hemp” beyond the terms of the 2014 Farm Bill to include not only “the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant,” but also “the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids… with a [Delta 9] concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

Similarly, in 2018, Minnesota adopted the Minnesota Industrial Hemp Development Act,3 which expressly authorized the cultivation, processing, possession and sale of hemp and hemp-derived products. See Minn. Stat. sec. 18K, subd. 3; Minn. Stat. sec. 18K, subd. 3.

And with that, the CBD industry was born. Cannabidiol, or CBD, is one of more than 100 cannabinoids, including Delta 9, found in the hemp/marijuana plant. The human body’s complex endocannabinoid system has receptors for cannabinoids found in the cannabis plant. Because cannabis has been federally illegal for so long (and essentially unavailable for testing), there is very little scientific research on how cannabis interacts with the human body. Anecdotally, however, many people use CBD in place of aspirin to treat aches and pains. Some claim that CBD has a calming effect that helps them sleep. Interestingly, most states that legalize marijuana still have robust CBD markets because CBD seems to work better in combination with a Delta 9 concentration higher than 0.3 percent but low enough that it does not produce a “high” in the consumer.

Other cannabinoids that have garnered attention include CBG, CBN, and CBC. But one cannabinoid in particular has outpaced the others: Delta 8 THC. Often referred to as “marijuana light,” Delta 8 has become widely available throughout Minnesota by benefitting from a legal loophole. Neither the federal law nor the Minnesota law that legalized hemp places restrictions on Delta 8. Rather, each law only addresses allowable concentrations of Delta 9. Arguably, therefore, so long as Delta 8 is derived from hemp, it is legal in Minnesota.

At least that appeared to be the case until the Minnesota Court of Appeals issued its decision in State v. Loveless in September 2021.4 As noted above, following the federal legalization of hemp, Minnesota adopted laws that expressly legalized the sale of processed hemp, including hemp-derived liquids.

In Loveless, however, the appellate court noted that although Minnesota removed hemp from the state’s Controlled Substances Act (CSA), it failed to remove non-plant Delta 9 from the state’s CSA.5 Consequently, the court upheld a man’s criminal conviction because he possessed a liquid that contained Delta 9 even though the prosecution failed to prove that the liquid contained more than 0.3 percent Delta 9. As one hemp retailer noted, “It goes without saying that all hemp growers, processors, and retailers could be convicted under such an interpretation. It ought to cause an outcry of concerns for the public.”

The appellate court noted that, despite statutory changes expressly authorizing the cultivation, processing, and sale of hemp, “the legislature did not amend the relevant provisions of chapter 152 [the CSA] to make it lawful to possess a liquid mixture with a low concentration of [Delta 9].” Although the Minnesota Supreme Court accepted review of Loveless, a legislative fix may be required to close the Loveless loophole.

As noted above, many observers believe that Delta 8 was legalized through the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill and Minnesota’s hemp statute. As CBD shops attempted to weather the “Green Rush” of entrepreneurs, many retailers reported that sales of Delta 8 were the only thing keeping them in business.

It should come as no surprise, however, that Delta 8 has begun to draw increased scrutiny from regulators. A few cases in point:

• At least one CBD shop in Northwest Minnesota was threatened by local law enforcement—who, citing Loveless, ordered all THC products off the shelves, even those with less than 0.3 percent Delta 9.

• Similarly, a CBD shop in southern Minnesota was targeted with a cease-and-desist notice from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture for selling Delta 8 “gummies.”

• A few months ago, the City of Stillwater enacted a moratorium on all new CBD retailers.

• Recently, too, local law enforcement executed search warrants against a “smoke shop” and its owners in Park Rapids, during which police seized hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of hemp-derived products.

In the meantime, although briefing is underway on Loveless at the Minnesota Supreme Court, the high court likely will not issue a decision until late Summer 2022. Legislation aimed at closing the Loveless loophole is currently winding its way through the labyrinthine committee process at the Legislature. Legislative efforts to expressly outlaw Delta 8 are expected, too. Even if Minnesota prohibits Delta 8, however, it is widely available for online purchase from companies located outside Minnesota. In light of all this, the legality of hemp-derived products will remain muddled even as nearby states continue to legalize adult-use marijuana.

JASON TARASEK is a cannabis attorney and lobbyist with Minnesota Cannabis Law. He represents clients in the hemp/CBD industry in Minnesota and Wisconsin, clients in the medical-marijuana industry in South Dakota, and clients in the adult-use marijuana industry in Michigan.

Notes

1 See 7 U.S.C. §5940(a).

2 Id. at §5940(a)(2).

3 Minn. Stat. §18K.01, et. seq.

4 State v. Loveless, 2021 WL 4143321 (Minn.App. 9/13/2021).

5 Id. *10